When the quadruple-murder trial against Jeremy Skibicki began on the last Monday in April, the public ear was pressed to the courtroom door, and James Culleton was sitting on the other side, with a sketchbook resting on his lap, a watercolour pencil in his right hand and history transpiring in front of him.

Skibicki, 37, of Winnipeg, was in court facing first-degree murder charges in relation to a femicidal spree that resulted in the deaths of four Indigenous women — Morgan Harris, Rebecca Contois and Marcedes Myran — and one unidentified person who’s been given the name Mashkode Bizhiki’ikwe (Buffalo Woman) by leaders within the Indigenous community.

Those deaths led to calls to “Search the Landfill” for the victims’ bodies, a pained and nation-spanning plea that became a divisive issue during last summer’s provincial election campaign.

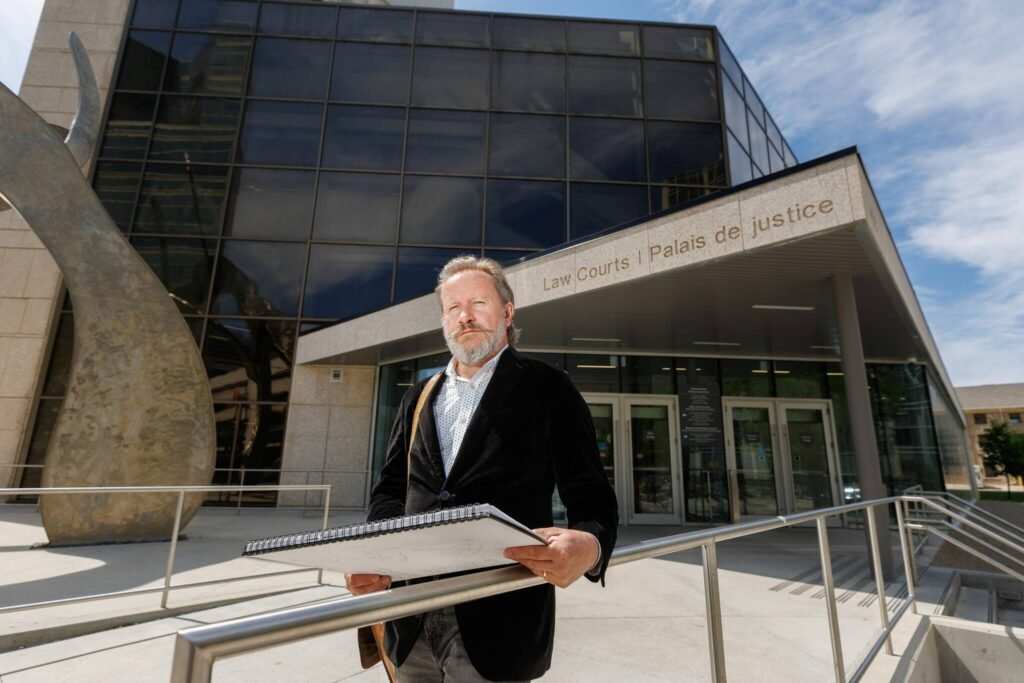

MIKE DEAL / FREE PRESS James Culleton, 50, has been a professional artist since 1997.

Before the trial began, thousands of words had already been written about the case — on the pages of newspapers, across corporate windows, in impassioned social media screeds and on picket signs outside the Manitoba legislature.

When Skibicki arrived in the courtroom that day wearing a grey T-shirt and track pants, thousands more words were written as his defence lawyers argued against the inclusion of a jury, jostling with Crown prosecutor Renee Lagimodiere while Court of King’s Bench Chief Justice Glenn Joyal carefully considered the potential influence of pre-existing bias on the proceedings at hand.

That was the story of the day — not a sorrowful recounting of events, nor a riveting opening statement — but instead a question of public knowledge and opinion.

As the lawyers made their arguments, Culleton looked up and began to draw, scribbling into his pad the scene as he saw it.

Rendered in a twitchy black line threaded across a white background, Culleton’s drawing made Joyal — resting his chin in the crook of his hand — the focus, drawing the eye toward the cautious nature of such delicate decision-making.

In his style — a quarter each of New Yorker cartoonist Roz Chast and her late colleague George Booth — the courtroom seems unpredictable, the outcome open-ended.

“I have a distinct style when I draw. What I give them is what I’m seeing.”–James Culleton

“I have a distinct style when I draw,” says the 50-year-old Culleton, who has been a professional artist since 1997. “What I give them is what I’m seeing.

“They’re looking for a non-partisan version of the scene, and to the best of their ability, a courtroom artist tries to draw the scene without putting their emotions into it.”

The next morning, the drawings produced by Culleton were featured prominently in local media coverage of the proceedings, including one on the front page of the Free Press, which participated in a cost-sharing agreement with other outlets to use the courtroom sketches. By week’s end, they had been published in the Toronto Star, the Globe and Mail and on the BBC.

JAMES CULLETON ILLUSTRATION King’s Branch Justice Glenn Joyal oversees the opening of accused serial killer Jeremy Skibicki’s trial.

As the drawings spread, opinions on Culleton’s courtroom work, especially on local factions of the internet forum Reddit, were divided between praise and the opposite. Some commenters felt his sketches weren’t realistic; others defended their merit. Still others were convinced they could do better. In a since-deleted post to a Facebook account, one local painter echoed that sentiment.

“Who is this guy?” he asked.

Culleton is a dynamic artist who, throughout his career, has embraced the word “yes,” working as a furniture designer, songwriter, children’s entertainer, arts administrator, sculptor, metal fabricator, drawing teacher, college instructor and more.

“I survive as an artist because I’ve decided to choose 100 things and not say ‘no’ to many of them,” he says, listing off oddball projects — a pink flamingo made of golf balls, a giant rubber chicken paraded down Main Street, a foam fabricated Jeep hanging in a Princess Auto shop — as evidence.

“I survive as an artist because I’ve decided to choose 100 things and not say ‘no’ to many of them.”–James Culleton

In 1992, his pencil drawings of NBA all-stars Michael Jordan, Isiah Thomas and James Worthy decorated the margins of his Grade 12 Transcona Collegiate yearbook. His first-ever mural was of the school mascot — the Titan – sprawled across the gymnasium in a horse-drawn chariot.

After graduating, Culleton enrolled at the University of Manitoba, where he completed a double major in painting and drawing, studying under acclaimed artist Diana Thorneycroft.

In September 2001, a Hieronymus Bosch-inspired oil painting of his was removed from a group exhibition at the then-St. Boniface College.

Considered provocative for its depiction of a papal figure in close proximity to a bare posterior, Culleton considered Holy Water to be a tasteful, if cheeky, commentary on masculinity, femininity and contemporary culture, but it rankled the school’s religious establishment.

“It’s innocent,” Culleton told the Free Press. “One person told me (the papal headwear) looked more like a Burger King hat.”

Meanwhile, he was working as a designer for Palliser Furniture as his day job. For nearly 15 years, he worked as the company’s design director, later going independent.

JAMES CULLETON ILLUSTRATION Jeremy Skibicki in court Monday, May 6, 2024.

In 2016, he was awarded a Pinnacle Prize from the prestigious American Society of Furniture Designers in the motion upholstery category; the next year, a piece of his designed furniture appeared in the Alexander Payne film Downsizing.

“Matt Damon is there, sitting in a home theatre piece of mine,” he says.

Much of his downtime was spent at downtown music and art spaces, where he mingled with like-minded oddballs, including prominent painter, the late Cliff Eyland.

In the early 2000s, after devoting the bulk of his early career to more rigid work, Culleton began experimenting with “blind gestural drawing” while at ALFA, an artist space across from the University of Winnipeg.

Drawing without looking freed Culleton’s line, leading to what has, in the years since, become his signature, love-it-or-hate-it style: a twitchy, scratchy mirror of what’s in front of him.

Long before he modified that approach to the courtroom for the first time in 2018, Culleton used quick, blind gestural drawing to showcase Manitoba musicians.

Culleton’s musical instrument sculptures on the facade of the West End Cultural Centre.

In 2011, he selected 300 illustrations for a self-published book called Lyrical Lines, depicting artists including Chic Gamine, Big Dave McLean, Old Man Luedecke and Loreena McKennitt.

One of his most prominent public artworks is the group of musical instrument sculptures gracing the facade of the West End Cultural Centre.

Culleton was around musicians a lot because he was one, too, releasing his first of eight albums, Brokenhead, in 2003. Track 4 reflects on his struggles as an artist to make both a living and a body of work he believes in. The title? Right Arm for Sale.

On his 2024 album Superfun Too!!, Culleton details his illustration practice on a song aptly titled I Draw with Squiggly Lines.

“Some artists paint the world they see, some artists draw people realistically,” he grumbles.

“Some artists collage from things that they find, some quilt and sew things rather divine. But me? I draw with squiggly lines. I draw with squiggly lines. Sometimes I look, sometimes it’s blind, I draw with squiggly lines.”

He might be playing it in a few weeks at the Winnipeg Folk Festival.

“Lucinda Williams is in the top right-hand corner of the poster, and James Culleton is in the bottom left with the letters piling into each other,” he says.

In court, Culleton attempts to blend in as he plays his part.

“I often wear black or grey,” he says. “I’m not wearing a red beret.”

Courtroom sketch artists have been employed in North America since at least the late 19th century, predating the newspaper photograph.

Even after the risk of shattering flashbulbs dissipated, the artist continues to offer a visual representation of courtroom proceedings, not just in Manitoba, but across the continent. Photographs of Donald Trump are plentiful, but courtroom drawings have helped illuminate the former American president’s ongoing trial in a novel fashion.

In a sketchy digital world marked by AI-doctored photographs, the hand-drawn reality still conveys a feeling of purpose, humanity and honesty.

JAMES CULLETON ILLUSTRATION Opening of accused serial killer Jeremy Skibicki’s trial.

“As it relates generally to the use of courtroom drawings, the objective should be to provide a replication of what’s occurring in a courtroom,” says Aimee Fortier, a spokesperson for the Manitoba Courts.

“In realizing this objective, one might reasonably expect an accurate resemblance and one that is commensurate with the seriousness of the proceeding being sketched. One might further expect any drawing to not be one allowing for artistic impression or something of a simplistic or casual nature, such as a caricature or stick drawing.

“These factors together, with the accompanying news article reporting on the court proceeding, best serve the role of providing an accurate, educative, and dignified representation of the court process.”

His former teacher appreciates his approach.

“With hours and hours of hard work, James has made his gestural contour drawings one of his signature styles,” Thorneycroft says.

“His natural tendency is to add a bit of whimsy, which sometimes slips into his court drawings, which I suppose, should be as “realistic” as possible, but you know right away it’s one of his compositions. I think they’re pretty great.”

Just as they’re described in different words, each trial Culleton covers is described with different visuals.

JAMES CULLETON / THE CANADIAN PRESS FILES Canadian fashion mogul Peter Nygard appears in front of a judge in court in Winnipeg on Tuesday, Dec. 15, 2020, in this court sketch.

Peter Nygard, the disgraced former fashion mogul and now-convicted sex criminal was masked during court hearings, with his hair up in a bun, looking dishevelled and attempting to evade the view of the courtroom artists.

On the first day of the Skibicki trial, the artist tried to capture the scene as it related to the story, with plans to focus on different visual elements as future court sessions rolled on.

“There’s a lot of pressure, certainly, and I am clearly not going to glorify these people with my drawings, but I want to be honest in my depiction,” says Culleton, who juggles such journalistic and ethical considerations as he sketches.

“But if I go in there and do a likeness of someone, is that more honest than a photograph? Maybe it’s not about honesty. Maybe it’s something else.

“I have this question in my head all the time, and I can’t say that I have an answer.”

After all, Culleton’s not the judge. He’s just there to draw him.

ben.waldman@Winnipegfreepress.com

Ben Waldman

Reporter

Ben Waldman is a National Newspaper Award-nominated reporter on the Arts & Life desk at the Free Press. Born and raised in Winnipeg, Ben completed three internships with the Free Press while earning his degree at Ryerson University’s (now Toronto Metropolitan University’s) School of Journalism before joining the newsroom full-time in 2019. Read more about Ben.

Every piece of reporting Ben produces is reviewed by an editing team before it is posted online or published in print — part of the Free Press‘s tradition, since 1872, of producing reliable independent journalism. Read more about Free Press’s history and mandate, and learn how our newsroom operates.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.