Giulia Cenci spends her days imagining new worlds. Her sculptures, made with a mix of industrial and organic materials, contemplate the interconnectedness of all beings, and provocatively synthesize animal, human, and vegetal forms.

Cenci (b. 1988) splits her time between the Netherlands and her native Italy, but over the past several years, her studio, in the south of Tuscany has emerged as the locus of her creative life. Here, in a stable converted into a multiroom studio, Cenci brings to life large-scale evocative sculptures with a team of assistants. Her works are often formed from melted-down scrap metal from farm tools, old car parts, and other disused machinery—which she forges on-site. The sculptures themselves conjure up a wild kingdom of fantastical creatures with references to wolves and dogs, mask-like human faces, spindly vegetal tendrils, and more.

These chimerical works have earned Cenci growing art world recognition. In 2022, the film dead dance made with Domenico Palma, was presented in “The Milk of Dreams” at the 59th Venice Biennale, and transported viewers to the Tuscan landscape where Cenci fabricates her works at a unique intersection of nature and industry.

Giulia Cenci, secondary forest (2024). Aluminum, iron, threaded rods, ivy. A High Line commission. Artist Studio View. Photo by Nicola Gnesi. Courtesy of the artist and Friends of the High Line. ©Giulia Cenci.

Right now, Cenci’s new installation secondary forest is on view at the High Line in New York, as part of an esteemed commission series (through March 2025). In the work, botanical and woodland imagery appear enmeshed with mammalian forms, along winding along a steel grid armature traversing the park. In some ways, secondary forest alludes to the history of the Meatpacking District as well as the High Line’s transformation from a rail line to a public park, underlining a site specificity important to her practice.

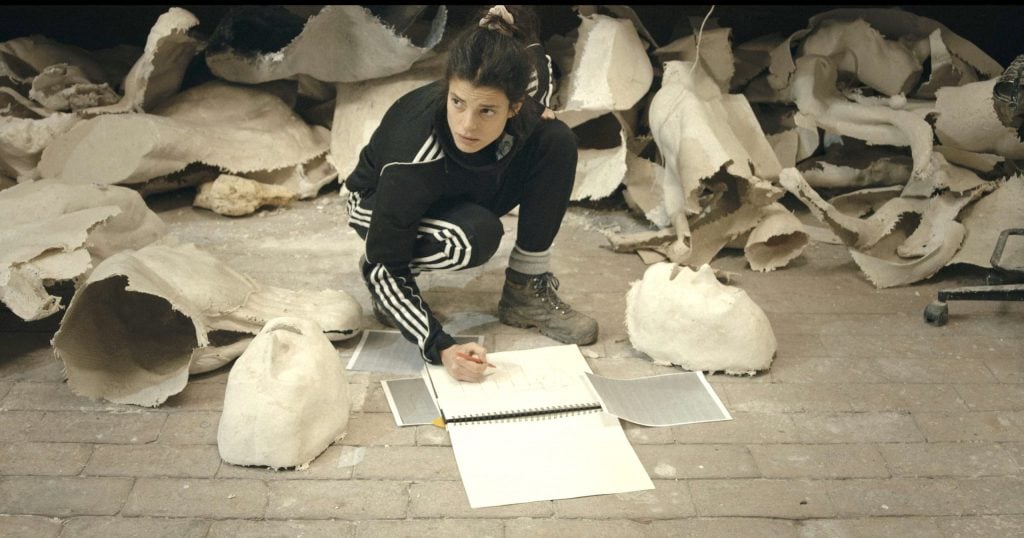

This summer, Cenci took us on a tour of her multifaceted studio in the sunburnt hills of Tuscany, offering an intimate look into her practice.

Giulia Cenci, studio view, 2024. Courtesy the artist. ©Giulia Cenci.

You live and work between the Netherlands and Tuscany. Can you tell me about your studio? What kind of space is it?

Over the past few years, I’ve produced most of the demanding works in the studio in Tuscany. It is an old stable in Cortona’s countryside, near the border with Umbria. The studio’s structure is organized by its original purpose as a stable and is divided by “boxes”—low walls dividing four identical spaces where the animals once lived. Each of these spaces has a door to the outside, but I created a few passages to cross them all from the inside, making it more practical. I love to use these spaces as a mental separation, each with a specific use.

The first box is the main entrance, where the office is located. Here I work on the projects, research, and collect elements. I share this space with an assistant. The first box is connected to the second, where I arrange and assemble the works in their very first origins. After sketching, I move the work into the third space, which acts as a metal and wood workshop. Here we define and stabilize the work to make it real. The fourth room is a transitional space that serves as a showroom area to see the finished work, pack it, make crates, and prepare it for shipping.

Still from Dead Dance, a film by Domenico Palma. 2023. 54’. Courtesy of Domenico Palma

Outside the studio is even more alive: we have a small wooden aluminum foundry where we melt mostly car scrap to make sculptures. This area is divided by uses as we mostly work with brackets to make molds before turning on the oven. It is self-made and follows our own rules and timeframes, but what I love is that the work is entirely made by our hands. The outdoor area can be extremely challenging when trying to make bigger works, but when we see the work’s relation with the rural landscape, we always get a new point of view.

Still from Dead Dance, a film by Domenico Palma. 2023. 54’. Courtesy of Domenico Palma

Your work fuses masks and animal forms made of industrial materials. How did you first start working with these materials and forms?

I guess it all comes from the need to connect my internal vision with my habitat. Over the years, I’ve lived in different places and confronted diverse cities, landscapes, people, and beings. It was important for me to try to connect with my habitat and fellow beings. All of a sudden, this entire population of objects, architectures, structures, and figures became the subject of the work.

The way society is structured determines my way of seeing the work. This process became a discovery of different possibilities of cohabiting. It was also a way to create rules, the need to get rigid and retain something but at the same time allowing for contradictions.

At some point, I realized all my installations have very specific dynamics. Ot wasn’t a matter of dividing and classifying, but a reason to share, mix, and meld. I forgot the usual hierarchies dividing us from the rest and tried to generate diverse connections, trying to incorporate and let different species, entities, and genders cohabitate. The entire structure of the work became indispensable as a support for bodies unable to stand themselves.

Giulia Cenci, secondary forest (2024). Aluminum, iron, threaded rods, ivy. A High Line commission. Artist Studio View. Photo by Nicola Gnesi. Courtesy of the artist and Friends of the High Line. ©Giulia Cenci.

How did you conceive of secondary forest now on view at the Highline? What was unique or distinct about this commission? How did you consider the history of the location and history of the area? How long did it take to create the work?

I always love to work in a specific context. The place and its structure are very good starting points for me to discover a new way to think and draw my work, and to define an innovative rule which I can use to define the installation. The High Line is a beautiful work itself; I immediately loved the way nature has been growing and devouring a manmade infrastructure. I started to fantasize about an area where different people, animals, plants, machines, and invisible entities are meeting and crossing, as well as how from underground to the top of the city’s skyline, the structure of society.

The work came very spontaneously while working on the structure of the tracks. I’ve been using old metal components of an agricultural truck (used to transport food and animals). Placed on several levels, the structures let the actual nature of the High Line grow and mix with an aluminum entity presenting vegetal, animal, and human prototypes melting and growing underneath, creating a new weird entity or landscape. I wanted to make plants bloom different species (even humans and animals), becoming essential and interconnected to each part of the installation. Having all these characters became indispensable to each other, including the structure, as elements redefining and generating a new life. We prepared the entire work in the studio. It was slow and long, because it was our first aluminum production, it took me approximately 3 months of drawings and projects and 5 months of production.

Giulia Cenci, studio view, 2024. Courtesy the artist. ©Giulia Cenci.

What kind of atmosphere do you prefer when you work? Is there anything you like to listen to/watch/read/look at etc. while in the studio for inspiration or as ambient culture?

When I enjoy the studio by myself, I love to watch documentaries and interviews with artists I love. Sometimes I work while listening to documentaries that focus on different historical periods, particularly ones when humans were vastly different from how we are today. I have some books that are crucial for my work, particularly poetry, which helps me maintain an open mindset.

When you feel stuck while preparing for a show, what do you do to get unstuck?

My problem is the opposite. Usually, I lack the time, funds, and space needed to materialize ideas, things I desire to accomplish. I am a maker. Everything I observe out of the corner of my eye seems like an opportunity to begin a project, an element to integrate, or a chance I don’t want to lose. I have a large collection of items stored in the back of my storage, things I hope to use for work or believe have great potential. I suppose one work leads to another. During the working process, there are numerous choices to consider, and I usually create additional pieces to ensure nothing is left out. It is quite disheartening, but at times I have to restrain myself as it would be overwhelming to accommodate everything.

Still from Dead Dance, a film by Domenico Palma. 2023. 54’. Courtesy of Domenico Palma

What tool or art supply do you enjoy working with the most, and why? Or is there anything in your studio that a visitor might find surprising?

Using a variety of materials is integral to my process and the way I create sculpture and installation pieces. I believe that all things hold potential and I enjoy valuing discovered items, whether they are considered ready-made or “pure” materials that are highly moldable and typically used for creating something new. I model some of the shapes in my works with clay, attempting to act as a machine while making a mannequin. I enjoy observing my subjectivity clashing with the concept of a stereotype. Many of these are combined with actual mannequins that I copy and duplicate in various forms, sometimes altering their position to suit the shapes I want to get. I also love to look for things, which often happens unexpectedly while engaged in other activities and can be a solitary pursuit. Drawing is essential too. Drawing is an activity that no one can separate me from, and it makes me feel secure.

Follow Artnet News on Facebook: