When artist Stephen Hutchings looks at a fallen tree, what he sees is a powerful symbol of life and death.

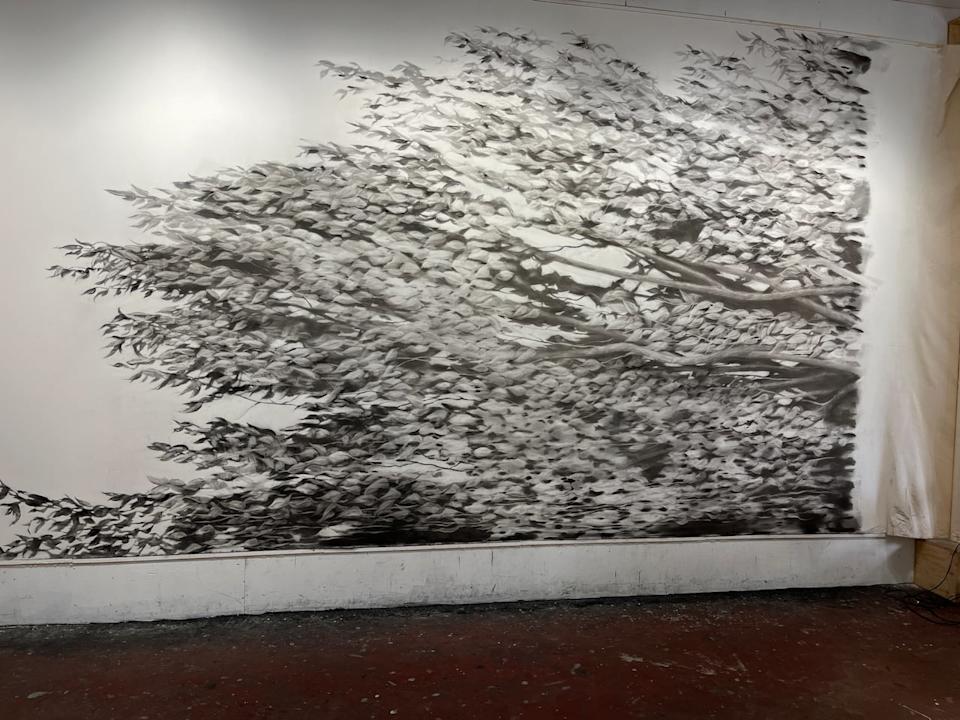

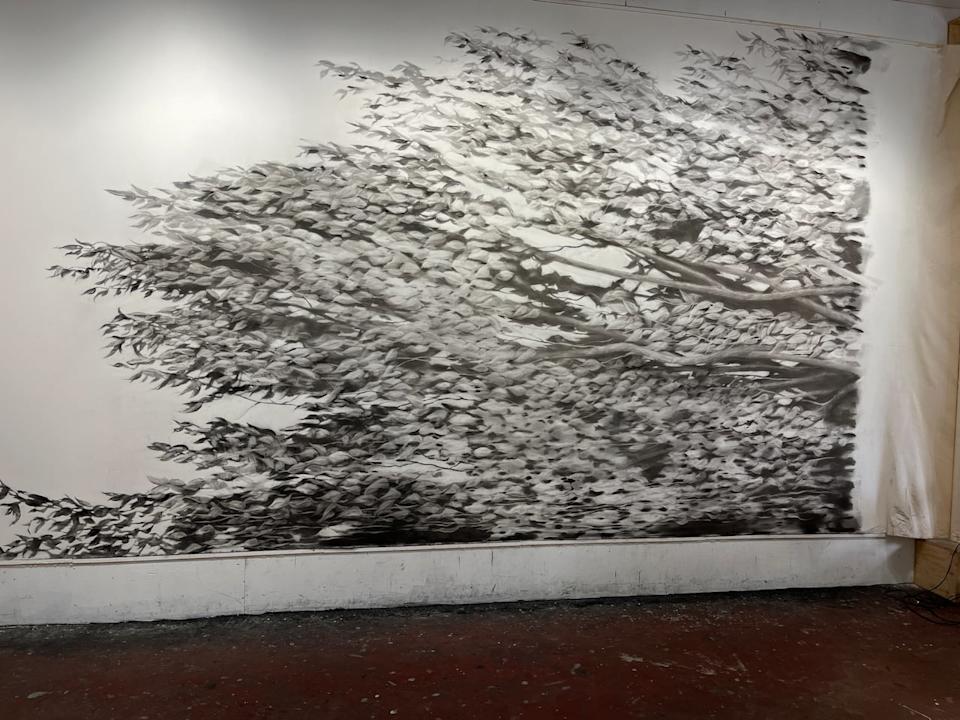

In a large studio in Florenceville-Bristol, Hutchings uses charcoal to craft the meticulous details of such a tree, working on canvas segments of about 10-by-18 feet before unrolling another section, with a goal of the completed piece topping out at a width of 40 feet.

“The tree is life-size,” he said.

“The top of the tree is on the left. The bottom of the tree, which will be of course the last thing I paint, are the roots, which have broken free from the ground.”

Three separate photos were used to capture different segments of Stephen Hutchings’s life-size fallen tree painting. (Submitted by Stephen Hutchings)

Despite the crushed nature of the leaves on the bottom and the freed roots, the tree is not dead, Hutchings said.

Trees serve as a representation of life from its earliest stages to the artist, symbolic of both resilience and fragility.

“The tree stands in as a metaphor for my take on where things are right now — the delicate balance between, you know, living and, I don’t know, not dying, but certainly not a happy scenario,” he said.

“It’s a precarious time and that’s what the tree represents.”

Hutchings said trees are anthropomorphic to him, meaning he can apply human traits to them without having to illustrate people.

Hutchings said he used to do a lot of portraits, but those are very specific, so painting trees allows him to make larger statements about the world without assigning an identity to the artwork.

Before colour is applied, Hutchings does a charcoal drawing. The first part of the drawing is seen here. (Myfanwy Davies/CBC)

He hasn’t always tackled things on a large scale. He took almost two years away from painting to work on himself, doing hundreds of three-inch graphic sketches each day. Most didn’t look like much, but they meant something to him, representing “states of grace” or soulful expressions.

Until one day, someone came in and complimented Hutchings’s “great bushes and trees.”

That was his “aha moment.” Stepping back and looking at the sketches, he realized they were essentially bushes and trees.

From itty bitty to larger than life

So within a week, Hutchings ordered canvas and did a 10-foot rendition of one of the little square bushes.

“All of a sudden … it had reality to me when it was, in this case, over life-size.”

Painting on such a large is very physical. He went from doing something that focused completely on the fingertips to something that involved scaffolds, ladders and rollers.

And going from being able to see everything on one tiny canvas to a massive project that needs to be completed in parts, Hutchings said much of the work is an act of imagination. He keeps a very clear image in his head of the part of the tree he’s working on.

Hutchings first completed smaller-scale sketches of the piece that would eventually be 40-feet wide. (Myfanwy Davies/CBC)

After completing the full large-scale charcoal drawing, the colour is next. Hutchings employs a four-colour process often used in the graphics world, paired with a 19th century technique called glazing.

He applies very thin, translucent layers of yellow, magenta and blue to create the image.

The finished piece is on display at the Andrew and Laura McCain Art Gallery in Florenceville-Bristol and then in September it will at the Beaverbrook Art Gallery in Fredericton as part of an exhibit called Theatre of Trees.

Hutchings said he hopes people will be impacted by the size of the image, both from viewing the finer details up close and the totality of the image from afar.

“I just want them to feel the rush of some kind of excitement and awe.”