THOMPSON, N.D. — Sitting in the pews in many churches throughout the Midwest, members of the congregation view paintings of biblical scenes behind the altar every Sunday, but they may know little or nothing about the artist who created them.

Capturing the imagination and illustrating crucial moments in the life and ministry of Christ, Sara Kirkeberg Raugland painted altar pieces mainly for Norwegian Lutheran churches. It is estimated that she painted about 300 altar pieces between 1889 and 1916, all while raising two children.

Her paintings hang in churches throughout the Dakotas, Minnesota, Wisconsin, Michigan, Iowa and Nebraska, as well as Illinois, Idaho and Washington state, according to research conducted by Elaine Ask, of Chatfield, Minnesota. Raugland is Ask’s great-great-aunt.

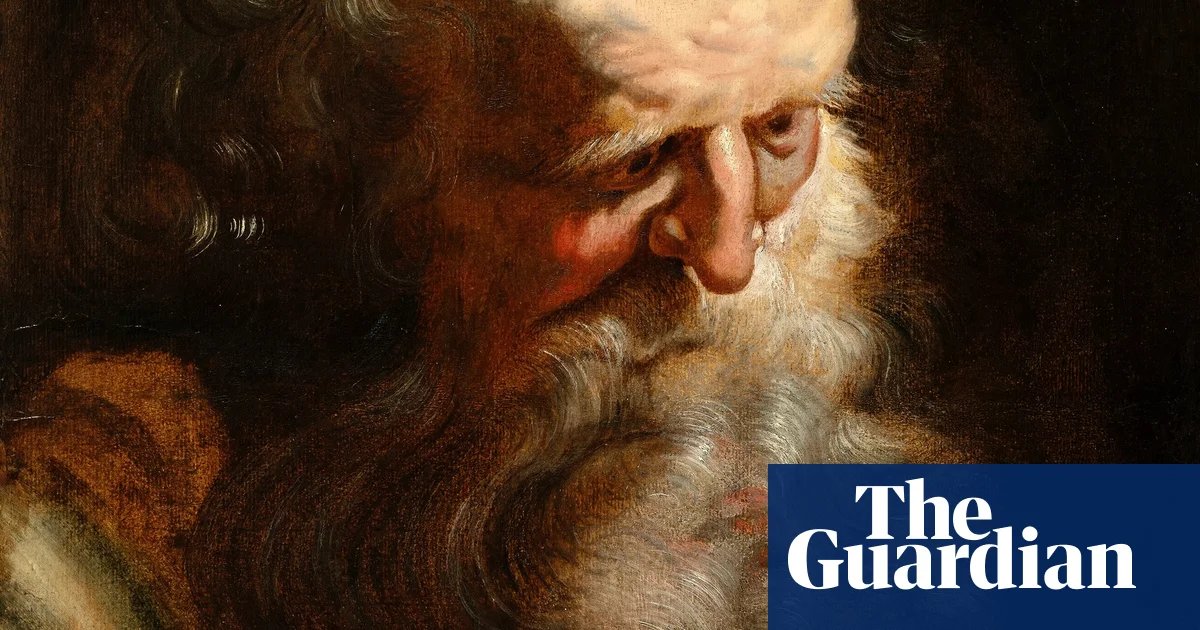

The altar painting at East Walle Lutheran Church in rural Thompson depicts the Crucifixion of Christ, with Mary and John as witnesses. The painting is about 30 inches wide by 7 feet high. In the foreground lies a sponge affixed to a rod by which Jesus was offered sour wine — an element rarely if ever seen in such paintings.

Marsha Gunderson, a local historian who served on the board of directors of former Preservation North Dakota, worked on a project to preserve the history of prairie churches. The project was designed to help preserve aging churches and provide grants to congregations to support those efforts.

In her scholarly historical work, Gunderson said she has seen “a lot of church altar paintings, but this is one of the darkest and most somber,” both in the artistic tone and psychological effect.

Eric Hylden/Grand Forks Herald

Another Raugland altar piece, an oil-on-linen painting in Grue Lutheran Church in rural Buxton, is 6 feet high by 37 inches wide, Sally Friese Hoffman, of Fort Collins, Colorado, wrote in a church history. Hoffman, who grew up in Traill County, is working on the project to restore Grue Lutheran Church, which closed in 2020.

In 1897, when the Grue congregation was ready to install the final touch — the altar painting — Raugland “was their chosen artist,” Hoffman said. “Records do not indicate how the decision was made,” but one simple explanation is that members of the congregation met her socially during the years she lived with her two brothers in nearby Cummings, North Dakota.

“(Raugland) most likely hoped her painting of ‘Jesus in the Garden of Gethsemane’ would please the congregation — maybe even help ‘save’ some souls,” Hoffman said, “but little could she know that, years later, that same painting might actually help to save the church building from being burned.”

The painting in Grue Lutheran Church, “Jesus in the Garden of Gethsemane,” was a direct copy of the 1890 original by German artist Heinrich Hoffman.

“Like many other European religious paintings, it ended up in the United States, a quirk of fate which later saved it from being destroyed during WWII,” Hoffman said. “(It) was one of the most popular paintings in the world, and without a doubt was one of the most widely copied.”

A native of Iowa, Raugland was born in 1862 to parents who emigrated from Norway in 1848.

In 1882, nine years before her marriage to Carl Raugland, she joined her two brothers, Knud Anders Kirkeberg and Gunder Anderson Kirkeberg, in Cummings, North Dakota.

Contributed

In 1887, she left Cummings to study art in Minneapolis and, at some point, went to New York City to study the mixing of paint. By 1888, she was listed in the Minneapolis city directory as an artist, evidence of how quickly she gained skill and confidence, Hoffman said.

In the 1880s through the early 1900s, only a handful of Scandinavian artists were selected to paint altar pieces for churches in the Upper Midwest, and many eventually ended up in the Minneapolis-St. Paul area, Hoffman wrote, citing Laurie Sommers of the Preserve Nordic Heritage Churches Project as a source.

“(They) first became active among Nordic-American churches in the 1880s, and, rather than creating folk art, they tended to copy well-known European paintings.”

Kristin Anderson, a professor of art history at Augsburg College in Minneapolis, said artists of Raugland’s era “worked not only with their own countrymen, but they also tended to sell predominantly to particular synods.”

Grue Norwegian Evangelical Lutheran Church was part of the Norwegian Synod, and most of Raugland’s paintings were placed in churches affiliated with the United Norwegian Lutheran Church of American Synod.

The synod did not passively provide a network of Norwegian church contacts. It provided active endorsements, according to author Chrissa Gerard, Hoffman wrote in her history. Rev. Ulrik Koren, synod president from 1894, “was a supporter of art in an area known more for its agriculture.”

As early as 1853, Gerard said Koren’s intention was to “make art part of the religious experience and … he encouraged hundreds of small rural churches to commission traditional altar paintings.”

Contributed

Another boost for her work came when Luther Seminary in Minneapolis placed one of her paintings in its chapel, surely to be remembered by seminarians as they dispersed to their own churches, Hoffman said.

Churches usually paid between $25 and $100 for each painting, and the more people in the painting, the higher the price, Ask said. The largest painting is 5 by 8 feet. Most of the paintings were vertical to fit in the standard altar space.

Raugland and her husband, Carl, who settled in Minneapolis, promoted her work in Norwegian publications and through the production of two catalogs — in 1893 and 1899 — complete with photos of paintings she had done for other churches.

Through these catalogs, Raugland advertised her paintings. A satisfied customer’s testimonial, translated from Norwegian, that appears in her catalog, reads: “She paints whatever Bible picture that they wish for in the size they order. She guarantees her work in this manner, that if the picture is not satisfactory, then it can be returned without any outlay from the congregation. The painting is usually in a frame and therefore ready to put up as soon as it is delivered. If other Bible Paintings besides those in this catalog be desired, then the order will be accepted.”

Contributed

Raugland repeated her subjects in altar pieces dated from the late 1880s to the early 1900s, Hoffman said. Most were of one large figure, because smaller figures were harder to be seen from the rear of the church — and the more people in the painting, the higher the cost to the church.

“Jesus and Peter on the Sea of Galilee” was the most popular, she said, followed by “The Good Shepherd” and “Jesus in the Garden of Gethsemane.” Nearly two dozen churches selected one of three slightly different versions of “The Crucifixion of Jesus.”

Ask and her husband, Peter, have been on a mission to find and document Raugland’s paintings and have located about 120 of them, she said, “which is pretty good,” considering the age of the paintings.

According to historical records, other locations in northeastern North Dakota that have, or did have, Raugland paintings include:

- Bottineau: Bottineau City Museum

- Carbury: Turtle Mountain Lutheran Church

- Cummings: Highland Lutheran Church

- Cooperstown: Trinity Lutheran Church

- Edinburg: Odalen Lutheran Church at Edinburg (painting lost to fire in 2007)

- Hatton: Bethany Lutheran Church, Goose River Lutheran Church (church burned in 1983) and Little Forks Lutheran Church

- Honeyford: St. Paul’s Lutheran Church

- Hoople: Park Center Lutheran Church

- Kloten: Valley Grove Lutheran

- Northwood: West Union Lutheran Church

- Reynolds: Zion Lutheran Church (now Reynolds Lutheran Church) and Stjordahlen Lutheran Church (a Reynolds parish, but located in Hatton)

- Thompson: St. Matthew’s Lutheran Church

- Walhalla: Big Pembina Lutheran Church (lost in 2014 fire)

And, in northwestern Minnesota, these locations have, or did have, Raugland paintings:

- Battle Lake: Trefoldighed Lutheran Church

- Fertile: Maple Lake Lutheran Church (two paintings, including one from the Hitterdal Lutheran Church)

- Fosston: Kingo Lutheran Church

- Pelican Rapids: Grove Lake Lutheran Church

Some of her paintings were sent to missions in China, Hoffman said, and one is in the Heensasen Lutheran Church of Valdres, Norway.

Raugland was one of the very few female altar-piece painters, and one of the earliest — male or female — to venture into the niche for which she is best known, Hoffman said.

“She was very talented at a very young age,” Ask said, noting that Raugland began sketching as a schoolgirl.

Ask is unsure how her great-great-aunt became interested in altar pieces, but speculated it was a popular medium.

“It was unusual for a woman to have a professional career as an artist at that time,” Ask said. “It must have taken a lot of guts. It was equally unusual to have her own listing in the city directories and to maintain a studio outside her home.”

Sara Kirkeberg Raugland stopped painting alter pieces in 1918 after the death of her husband, but continued creating small paintings while living with her daughter until 1960 when she died at age 98.