Few with an interest in art have not heard of Sir Alfred Munnings’s 1949 resignation speech at the Royal Academy (RA). His blistering attack on modern art, broadcast on the BBC and hailed by the public, if not the art establishment, was the climactic moment in a relationship with the RA that began in 1899, when his first two paintings, Stranded (of two of his cousins in a rowing boat) and Pike Fishing in January (of kind local man ‘Jumbo’ Betts), were accepted for the Summer Exhibition. In his engaging autobiography, An Artist’s Life, he calls that moment ‘infinite bliss’ and, as he became known and sent works every year, he ‘dreaded being rejected and out!’

Becoming RA president in 1944 was ‘an honour’ and he walked home through bomb-blighted London full of ‘lofty hopes for the future of English art’. However, his romanticism and ardent admiration for his British forebears, from Reynolds to Millais and Lucy Kemp-Welch, caused a swell of feeling against the turn 20th-century art had taken. ‘What are pictures for?’ he asked. ‘To fill a man’s soul with admiration and sheer joy, not to bewilder and daze him.’ Modern artists were guilty of ‘affected juggling’, anathema to Munnings’s egalitarian aims. Students were learning ‘to become what? Not artists’.

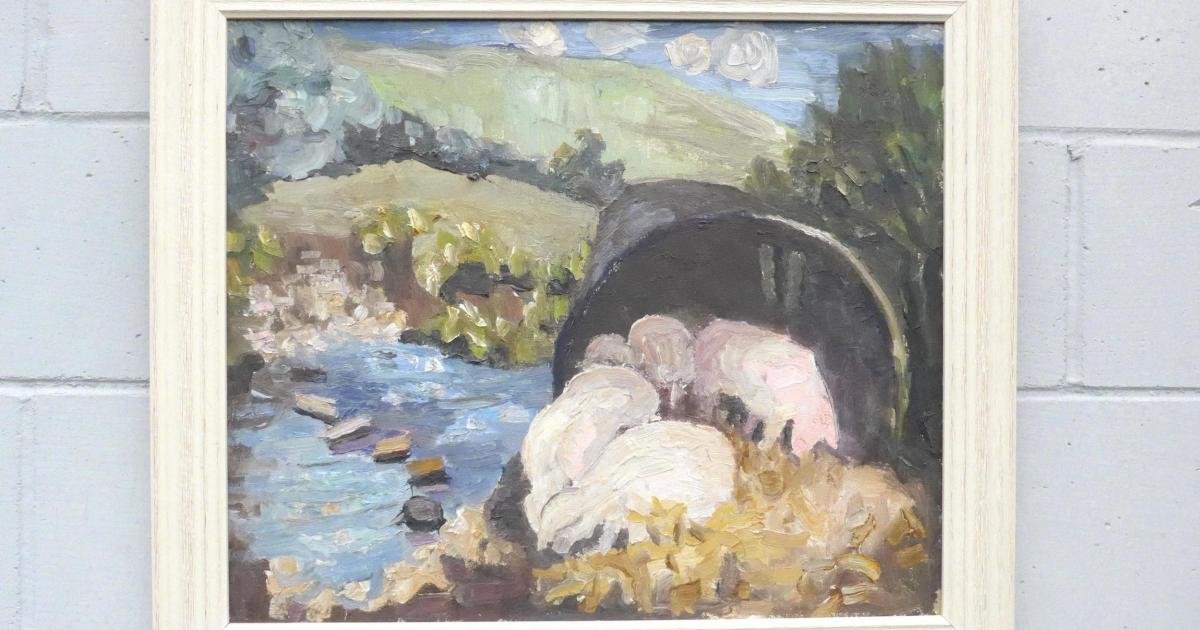

A Barge on the Stour at Dedham by AJ Munnings, c. 1935. Oil on canvas, 61 x 81.3cm.

(Image credit: The Munnings Art Museum)

When Churchill urged him to revive the Academy Banquet, with ‘Let’s have a rag’, the convivial Munnings eagerly agreed: ‘A rag — and a good party — that was the thing.’ Standing up to speak, he remembered Anthony Blunt, Surveyor of the King’s Pictures, saying that Picasso was a finer artist than Reynolds and launched into his excoriation of the art world. He accused it of ‘shilly-shallying’ and stated he would rather have ‘a damned bad failure, a bad, muddy old picture where somebody has tried… to set down what they have seen’.

His apoplectic words did him no damage: he wrote of receiving floods of letters in support and, in 1956, a retrospective at the RA resulted in queues to Piccadilly. His auction record is nearly $8 million, for The Red Prince Mare in New York, US, in 2004. Now, he is being celebrated with an exhibition from the British Sporting Art Trust, curated by Katherine Field, who remarks his continuing neglect by the critical establishment: ‘I was astounded that an artist of such technical mastery and brilliance seemed to have no place in the academic curriculum.’ The catalogue includes a foreword by The Duchess of Cornwall and essays by the likes of sculptor and Munnings historian Tristram Lewis, who emphasises the artist’s skill in bronze, as well as paint.

Under Starter’s Orders, c. 1951. Oil on canvas, 50.8 x 60.9 cm (20 x 24 in.). Inscribed lower right: A.J. Munnings.

(Image credit: The Munnings Art Museum (no. 135))

Munnings describes his rural childhood as the son of a yeoman miller in Mendham, Suffolk, with great affection. Neither of his parents was artistic, but they recognised the boy’s talent and he was apprenticed at the age of 14 to lithographic firm Page Brothers and Co, where his talent and humour emerged in advertisements for Colman’s Mustard and Caley & Son. In the evenings, he studied at the Norwich School of Art under Walter Scott, to whom he pays tribute in An Artist’s Life, together with the Castle Museum and Art Gallery curator James Reeve, who ‘lectured me on thoroughness in work’, and John Shaw Tomkins, director of Caley’s Chocolate, ‘full of energy and ideas’, who took Munnings around Europe.

A formative experience for the gregarious artist was his first trip to the races, with Ralph Wernham at Bungay, the ‘most vividly coloured phase of life I had yet seen’. The whirl of horses and punters inspired Munnings and he returned frequently to the racetrack throughout his career, capturing with dexterity the jostle of movement at the start, the flash of coloured silks and the horses’ gleaming flanks. His last ever commission was to paint The Queen’s Derby runner-up, Aureole, in which the Stubbs-like pose of the restless horse and vividly depicted people are given energy by the impressionistic sky.

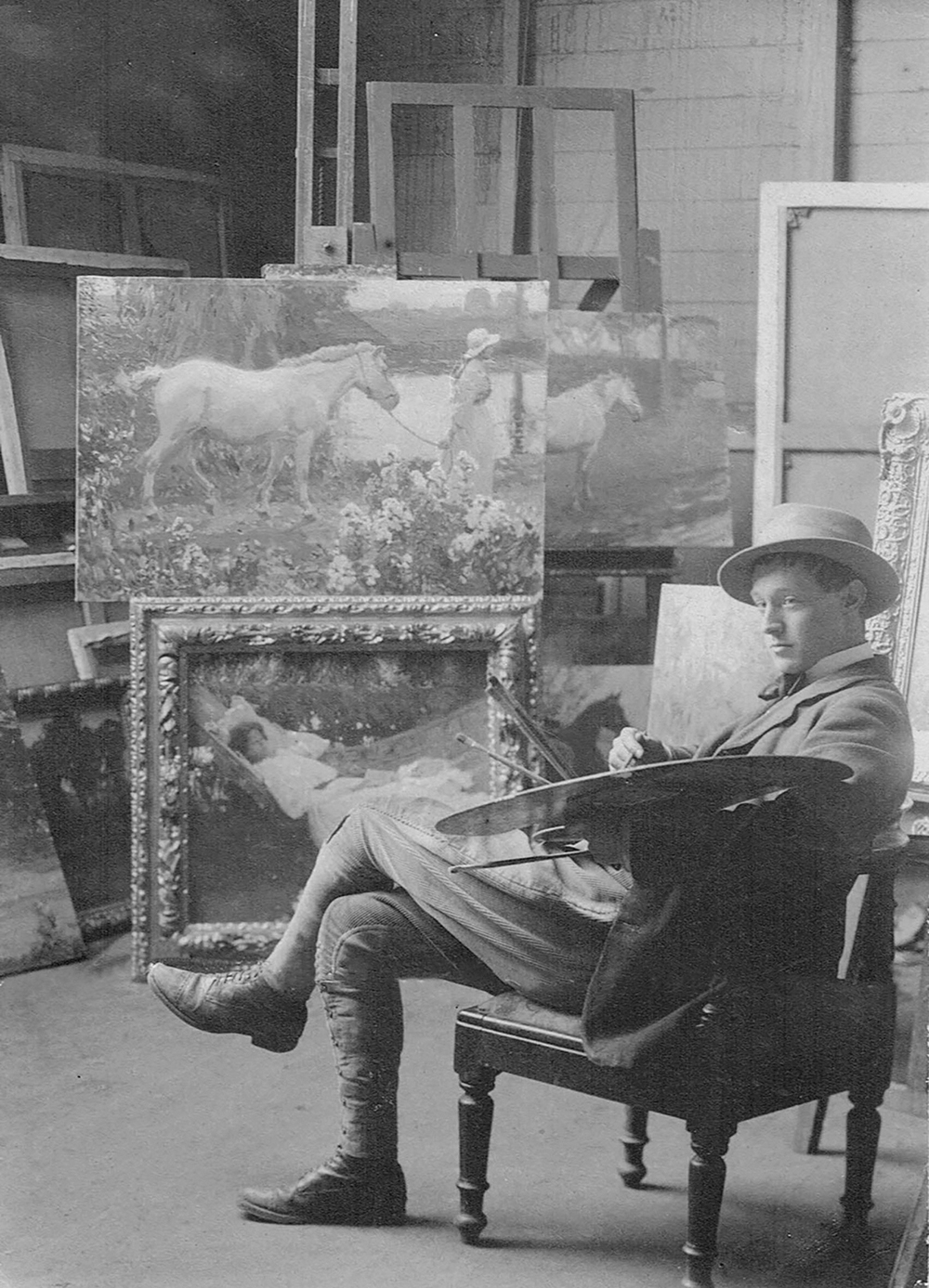

In studio with Path to the Orchard. The painting is clearly visible on an easel in an early photograph of Munnings in his studio at Swainsthorpe. He had a mind for self-promotion and took pains to ensure that he and his work were documented photographically throughout his career.

(Image credit: Courtesy of The Munnings Art Museum)

That last work was one of many grand commissions and portraits, from the Rothschild stud to Paul Mellon (whom he castigated for misidentifying a pollarded oak), and from Churchill, whom he also taught, to the Prince of Wales. The work gave him financial security and a glittering social life, yet he rued the effort and travel involved and was most content in the country, sketching.

Some of his happiest years were as a young artist living from sale to sale, when, true to his stated wish to paint truth, he worked outside with models equine and human, buying horses for their looks, despite their occasional tendency to kick carts to smithereens. Munnings travelled the lanes and hills of Norfolk with the gypsy groom Shrimp, ‘an indispensable model, an inspiring rogue and an annoying villain’, capturing light and cloud, sun-dappled flanks and flapping neckerchiefs with a natural spontaneity.

The idyll ended with the First World War. Munnings was barred from active service due to losing the sight in his right eye aged 21, when he impaled it on a thorn lifting a hound puppy over a fence, but he followed Cecil Aldin to a remount depot, at Caldecott Park, Berkshire, working with his ‘beloved horses’. In 1918, he joined the Canadian Cavalry in France as an Official War Artist under Gen Jack Seely, whom he immortalised in paint on Warrior, ‘the horse the Germans couldn’t kill’. He did come dangerously close to the ‘incessant din of the German bombardment’, but, typically, he wrote of ‘jolly nights in the mess’ and the Canadians loved his work: ‘He’s got your old horse, Bill!’ His 45 paintings were exhibited to acclaim in 1919.

Lamorna Inn, 1915. Oil on canvas, 50.8 x 61cm (20 x 24 in.) Inscribed lower right: A.J. Munnings.

(Image credit: The Munnings Art Museum)

Munnings hunted with packs across the country, from the West Norfolk to the Western, and his resulting paintings, sometimes with groom Ned Osborne in scarlet, are alive with wind and thrill. One depicts the day a valiant Cornish fox swam to safety below a cliff and he stopped the huntsman administering the coup de grâce, to the cheers of the field.

Munnings’s love for animals and the countryside, for the old ways and people he saw vanishing under the onslaught of the modern world, imbues his paintings. On his grave in St Paul’s Cathedral are John Masefield’s words: ‘Oh friend, how lovely are the things, the English things, you help us to perceive.’ For Munnings, the land of Gainsborough and Gray’s Elegy, of childhood games, sailing and hunting, gypsy caravans and hardworking country people, was always foremost and it lives on in his work.

‘Sir Alfred Munnings (1878–1959): A Life of his Own’ is at the Osborne Studio Gallery, London W1, until May 14 and the National Horseracing Museum, Newmarket, Suffolk, May 24–June 12 — www.bsat.co.uk

Study of the Start, 1951, by Sir Alfred Munnings (1878–1959). Courtesy of the Munnings Art Museum, Dedham, Essex.

(Image credit: The Estate of Sir Alfred Munnings, Dedham, Essex, DACS 2021)

Racehorse trainer Dan Skelton picks a classic Munnings image.

A Canadian Trooper an his Horse, Alfred Munnings (1918).

(Image credit: Beaverbrook Collection of War Art at the Canadian War Museum Ottawa, www.warmuseum.ca.)

Huon Mallalieu welcomes the opportunity to see a significant body of wartime paintings alongside other works by Munnings in his

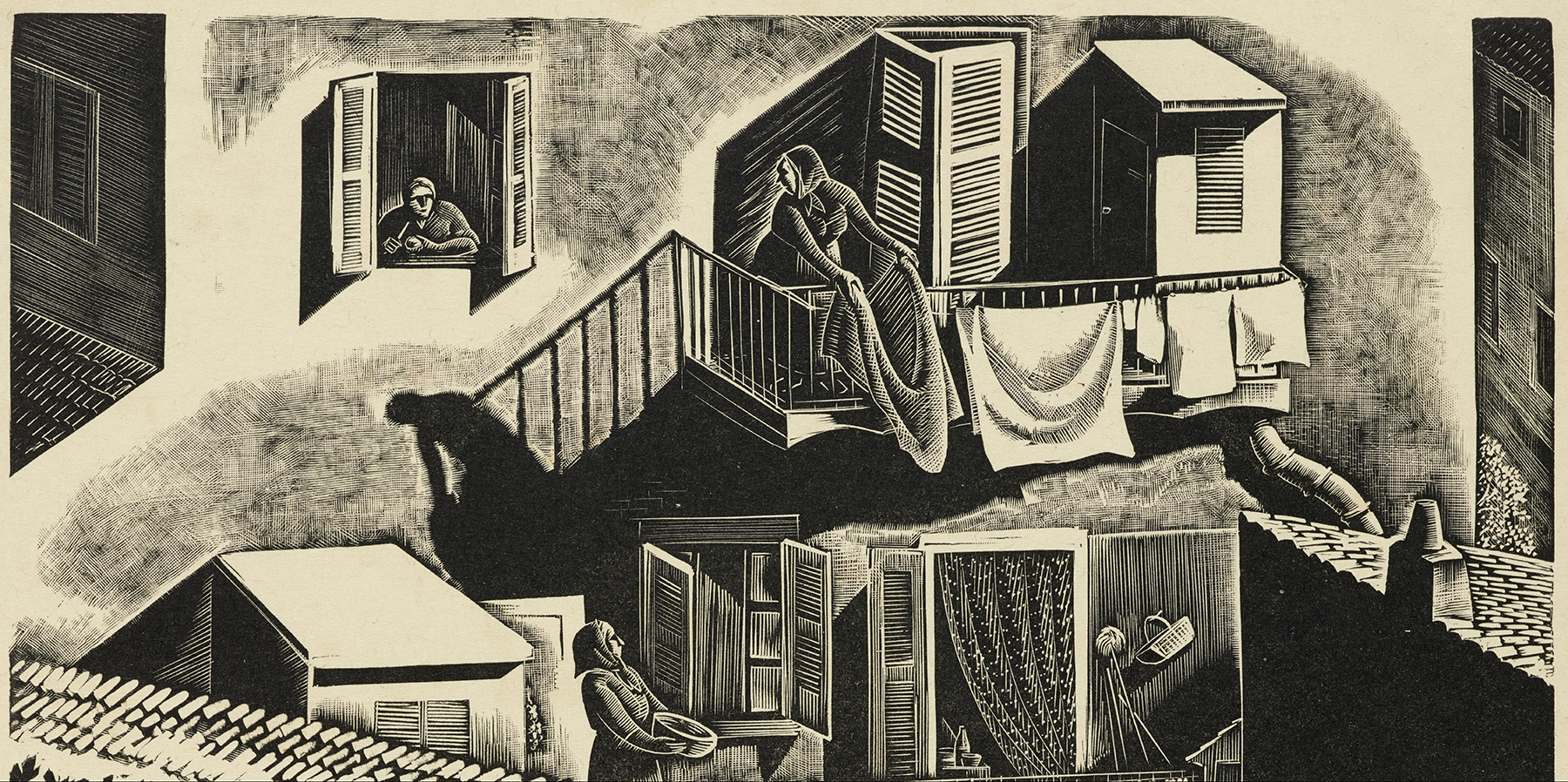

Gossip by Iain Macnab. ©Ashmolean Museum Oxford

(Image credit: Ashmolean Photo Studio)

Wood engraving commands laborious attention to detail, but the effects can be entrancing and varied. A new exhibition at the

Pinner Middlesex, UK. April 2018.Memorial Park. Panorama taken on a sunny spring day. West House and the Heath Robinson Museum in the background.

(Image credit: Alamy Stock Photo)

Huon Mallalieu tells the story of the small museum in Middlesex, where you’ll find the last records of the county