In a 2007 essay, art historian ShiPu Wang wrote that the works of Asian-American artists “are more than painterly creations that exude ‘transcendental beauty’ beyond cultural boundaries.” He added, “Their meaning and significance constantly shift and expand under different sociopolitical circumstances, and they do not remain incontrovertible objects or artifacts.” In her 1990 book, Mixed Blessings: New Art in a Multicultural America, Lucy Lippard wrote that “even for the displaced, the exiled, and the disoriented whose moorings have been cut loose, landing of some kind is necessary… The dialectic between place and change is the creative crossroads.”

At the Utah Museum of Fine Art (UMFA), the current exhibition Pictures of Belonging: Miki Hayakawa, Hisako Hibi, and Miné Okubo is a brilliant masterpiece on its merits, impressively commanding visitors to think anew about American modernism in 20th century, as suggested by the words of Wang and Lippard. With more than 100 works, including many that have never been publicly displayed before, the exhibition highlights these artists, who were among the most active and visible female artists of Japanese descent, born in the generations before World War II. A separate smaller exhibition but just as powerful in its representation, Chiura Obata: Layer by Layer documents the creation and conservation of the artist’s Horses screen (1932), one of the greatest 20th century works celebrating an iconic image of the American West (EDITOR’S NOTE: See tomorrow at The Utah Review for feature on Obata show.)

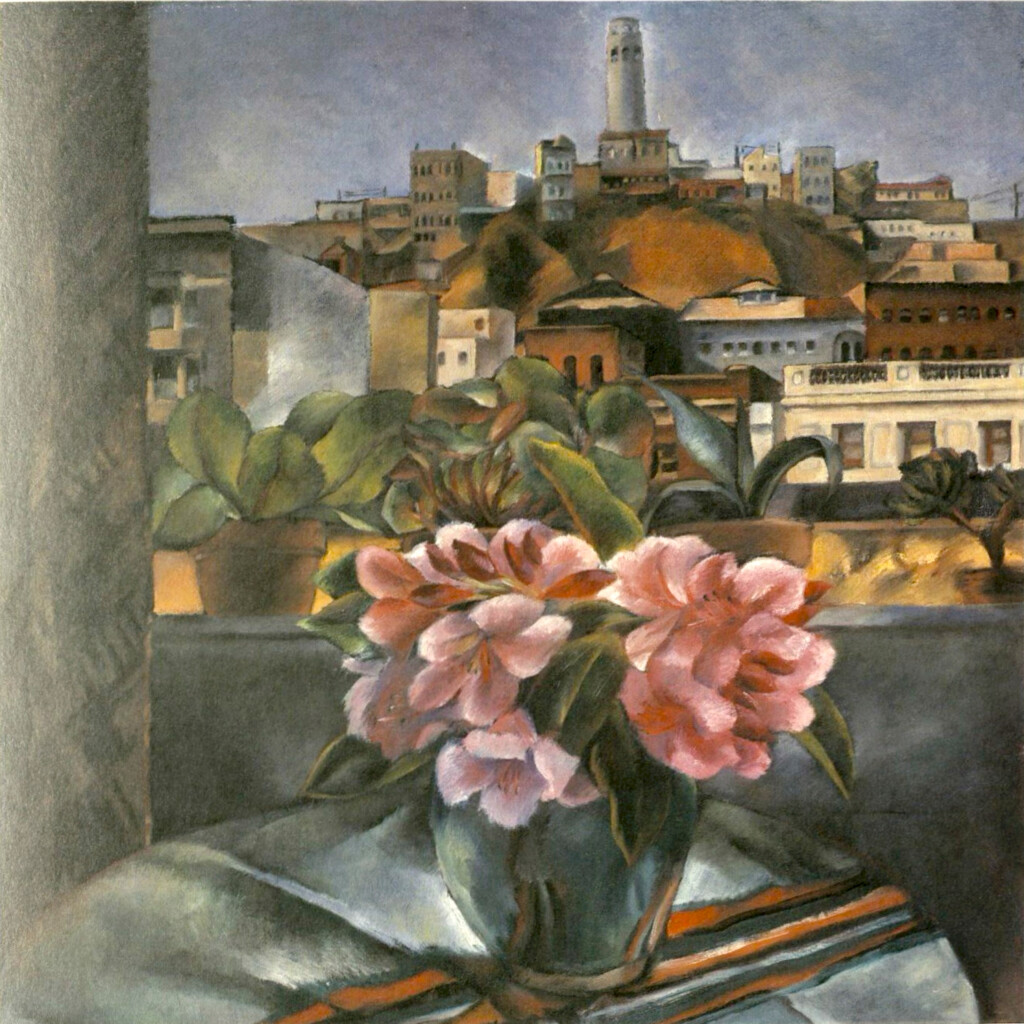

Oil on canvas, 24 x 20.25 in. Collection of the McCrossen Family

Pictures of Belonging, curated by Wang and organized by the Japanese American National Museum in Los Angeles, is unprecedented in its historic scope. Utah is the first stop for the exhibition, which eventually will land at the Smithsonian American Art Museum. Wang also curated Chiura Obata: An American Modern, which was at UMFA in 2018. That show cemented a relationship with Obata’s family through connections initiated by Wang, which led to the UMFA collecting 35 works from the artist’s estate in 2021.

Collectively, Hayakawa, Hibi and Okubo, each prolific in their respective regard, represent more than 80 years of active creation. Their lives encompassed a time of anti-immigration laws when Asian American immigrants were prevented from becoming naturalized citizens as well as the events of World War II that disrupted their lives and led to American citizens and immigrants of Japanese descent being interned in camps, including in Utah. Incidentally, Hibi and Okubo were imprisoned in Topaz, Utah, from 1942 until near the end of the war, as was Obata.

Among the most elucidating aspects of the show is the evolution of their work throughout their careers, all of whom started in California. Hayakawa and Hibi studied at the California School of Fine Arts in the 1920s and Okubo at the University of California, Berkeley, in the late 1930s. Even early in their careers, their respective work was acclaimed and awarded prizes. In addition to the artworks, the exhibition includes photographs of the artists at work and with family, as well as quotes that enrich our interaction and appreciation of the historical contexts.

Hayakawa (1899-1953) moved to Santa Fe in 1942 and remained there until her death at the age of 53 and Wang’s comprehensive research has filled many gaps about her life and existence. Hayakawa’s father had resisted her pursuing art as a career. Her first solo exhibition of more than 150 paintings was held in 1929 at Kinmon Gakuen, or the Golden Gate Institute, a Japanese American language school and cultural center located in the San Francisco Japantown district.

As with Hibi and Okubo, Hayakawa was wholly sensitized to her racial Other status in a country that aggressively pursued exclusionist and anti-immigration laws. In portraits, Hayakawa’s painting technique created complex, textured representations of individuals, including her 1926 Portrait of A Negro. Hayakawa’s portraits are scrupulous in discreet, intimate and respectful consideration, as she took care to gauge the extent and reach of the viewer glimpsing into her world. Colors are exquisitely graded for finding expressive textures.

When she was generous and effusive about chronicling her connection and love of landscape, the paintings are extraordinary. One of her most acclaimed works came from 1935, From My Window, which was accepted into two landmark exhibitions at the time: the opening display of the San Francisco Museum of Art (now SFMOMA) in 1935 and the Golden Gate International Exposition on Treasure Island in 1939. Hayakawa showed the Coit Tower, which had been completed two years prior, on top of the Telegraph Hill neighborhood and overlooking San Francisco. Likewise, a later oil painting, Angie (circa 1948–51) earned the First Premium Prize at the New Mexico State Fair in 1951, which she likely had submitted three years earlier to a Santa Fe show highlighting New Mexico artists.

With Hibi (1907-1991), who was born in Japan, and Okubo (1912-2001), who was born in California, we see the most prominent shifts in their visual aesthetic language from the prewar period through their experiences of incarceration and then an incredible flourishing of abstract composition after the war. Both artists were initially incarcerated at California’s Tanforan Assembly Center and then at Topaz in Utah. Okubo moved to New York City in 1944 where she worked as an illustrator for Fortune magazine. She brought along a good number of works that she produced before the war. Okubo’s Grocer Weighing Produce (1940), a work in tempera on hardboard, reflects an intriguing evolution in her aesthetic language that already was in motion before the war. This work evokes a style linked to Diego Rivera as well as another well-known Mexican muralist José Clemente Orozco.

The exhibition offers an eloquent and poignant representation of the prodigious volume of works that Hibi and Okubo produced during their incarceration. These works provide a 360-degree expressive view of life during incarceration and the emotional dynamics that were resilient as the counterpoint to a forlorn sense of forced segregation. From Topaz, Hibi’s Eastern Sky 7:50 A.M., dated February 25, 1945, is a landscape painting that conveys emotions with striking clarity through colors and hues. Writing about the painting some 30 years later, Hibi noted, “…I felt sad—heaven and earth, everything seemed grey—I used lots of grey color,” but “nature was always beautiful! The desert sunrise and sunset, so brilliant and so magnificent, somehow I could not bring out the brilliant colors on the canvas. The stars at night were another beauty—clean and clear!” The works’ historical importance in rounding out the chronicle that should never be subverted or obscured is profound.

Okubo’s Wind and Dust (1943), in opaque watercolor on paperboard, is an exemplar of the remote, stark surroundings that Japanese Americans endured in the camps and they had to find ways to sustain themselves against harsh conditions. Okubo’s aesthetic language expanded during this period, as the figures portrayed are rendered in curves and rounded shapes. In 1946, Okubo published a graphic memoir of her experiences, titled Citizen 13660.

In 1945, Hibi also moved to New York City, with her husband Matsusaburo George Hibi, who also was an artist, and their two children. Her husband died from cancer two years later and Hibi worked as a seamstress while raising her children. Contending with a fresh set of struggles in her life, Hibi continued to paint and took night courses at the Museum of Modern Art in the city, including a class with Victor D’Amico, a post-Impressionist, that was pivotal, as she liberated her aesthetic language that had been defined not only by her prewar experiences but also her ancestral Japanese upbringing. As Betty Kano explained in a 1993 essay for Feminist Studies, “ Hibi recalled that he exhorted her to make her ‘own statement,’ but she ‘didn’t understand what that meant’ and found it difficult to do; she thought it might be like creating a “child’s mind, [to] go back to nothingness.” …Her Meiji era (nineteenth century) upbringing, with its emphasis on total obedience, conditioned her to censor her ‘own statement.’”

The postwar aesthetics of liberation pops with astounding impact in the works of Hibi and Okubo. Indeed, Hibi took earnestly to the challenge that artist-teachers such as D’Amico put to her. Postwar works by Hibi spring from philosophical metaphors and symbolism or from poetry, with imagery rendered exquisitely through colors and textured brushwork. Hibi’s Poems by Madame Takeko Kujo (1970) is enlightening about the artist’s holistic evolution in her artistic language. Kujo (1887-1928) helped found the Buddhist Women’s Association in Japan. Hibi interpreted Kujo’s Yowakiga mamani (as weak as you are) and the result inspires us to reflect on how the works Hibi and Okubo produced during their incarceration sustained their will to live and thrive and girded their perseverance. Nature’s “blessings” (as Kujo articulated) could not be snatched from the persons who had been subjugated to callous human treatment. It was in those blessings that the artists highlighted in Pictures of Belonging found their “peace of mind.”

Okubo, who lived the longest of the three artists documented in the exhibition, explored enormous creative territory until the end of her life. She played with bold colors and simple forms that amplified her genuine appreciation of reimagining a world warmed by the constructive effects of fantasy. Proverb (1955) epitomizes how the artist moved on, without harboring bitterness. “There is not time enough to sit back and worry about an event of the past. It is human nature to look ahead and to hope and to strive for a better tomorrow…,” Okubo wrote in 1972. “[I]you want something done, you have to do it yourself…. It’s tragic—life, in every shape and form…. In my next life, I’ll come back as a Japanese Beetle!” Indeed, works such as Boy, Goat, Fruit (before 1972) confirm Okubo’s wholehearted commitment to express nature in its best foundational elements, never missing an opportunity to find wit and whimsy that can sustain and bless individuals when managing difficult times.

Hibi returned to the Bay Area in the mid-1950s and steadily gained acclaim through the rest of her life. At the age of 79, in 1986, she received a U.S. Congressional tribute, a commendation from the Arts Commission of San Francisco, and a declaration of June 14 as the city’s “Hisako Hibi Day.” Nearly four decades after it was initially published, Okubo’s Citizen 13660 received the American Book Award in 1984. Okubo testified before the U.S. Congress Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians, during which she urged the government to apologize to those who were unjustly imprisoned during World War II. Five years later, in 1988, the Civil Liberties Act was enacted, which included reparations and a formal apology to Japanese Americans who were incarcerated. When she was 79, she received a lifetime achievement award from The College Art Association’s Women’s Caucus for Art.

Along with the concurrent Obata room show, Pictures of Belonging is yet another milestone for UMFA, which has played a major role in recent years emphasizing how these four Japanese American artists, along with their colleagues, carved a prominent presence as among the greatest figures of American modernism in the 20th century.

The exhibition continues through June 30. For moor information about the exhibition and other museum programs, see the UMFA website.