Images of food that engage the eye and invite us to look closer are both beautiful and great for the appetite. Whether flipping through a celebrity chef’s cookbook, bingeing a cooking series or scrolling Instagram for must-try dining experiences, some images undoubtedly demand our attention more fully than others.

Contemporary food culture uses stylised imagery to draw us in and turbo charge our comestible desire. Whether these images are viewed digitally or in print, we all know the look: razor-sharp, close-up, colour-saturated images shot from above and eager to get the digestive juices flowing.

On a smartphone, these tasty images are in-your-face and only centimetres from the point of consumption: your mouth.

Dutch and Flemish still-life artists of the 17th century knew a thing of two about amping up food’s visual appeal. The Old Masters elevated seduction to an art form during the golden age of the still life. These artists were originators of a visual language that transports today’s fetishisation of food aesthetics and consumption. While many Old Masters produced flower paintings at the height of Tulip mania, the golden age of Dutch and Flemish art was also a sweet spot for food paintings, building upon earlier Spanish and Italian still life traditions.

Artists such as Jan van Kessel the Elder (1626–1679), Willem Claesz Heda (1594–1680), Clara Peeters (c.1594–c.1657), Willem Kalf (1619–1693) and Jan Davidsz de Heem (1606–1684) each developed a distinctive visual style in the “set table” genre that prefigures today’s food imagery.

Van Kessel’s set-table painting Still life on a table with fruit and flowers suggests that stock-in-trade visual techniques have changed little in around 400 years. Separated table objects pictured from an elevated perspective allow the eye to pick out and savour each food in turn. The texture and colour are highly legible, courtesy of the painting’s sharp realism.

Lighting techniques also choreograph the visual appeal. Subdued background lighting directs the viewer’s eye “downstage” to where the diner has apparently just stepped away, reinforcing both a sense of the meal’s freshness and the timelessness of the image. The orderly arrangement creates a visual symmetry, with the orientation of items directing the eye back “upstage” to the large central platter of fruit. The adjacent stand of blooms against the darkened background provides another pay-off for the beguiled viewer.

The early trend to visually separate foods across the whole tabletop succumbed to greater visual artifice. Paintings became increasingly stylised, compositions tighter and even with food stacked to create sculptural forms. Clara Peeters’ Still life with cheeses, almonds and pretzels exemplifies the beginnings of in-your-face imagery, reinforced by the plate of almonds and the pretzels that risk falling from both the table and the picture plane, right into the viewer’s lap.

Later styles of these set-table paintings were even more visually seductive. Jan Davidsz de Heem created lavish paintings in which luxury foods and visual textures comprised a sumptuous cornucopia, such as his Still life with fruit and lobster. Impossibly stacked objects seemingly defy gravity, drawing the viewer deep into the painting’s realm of optical interest.

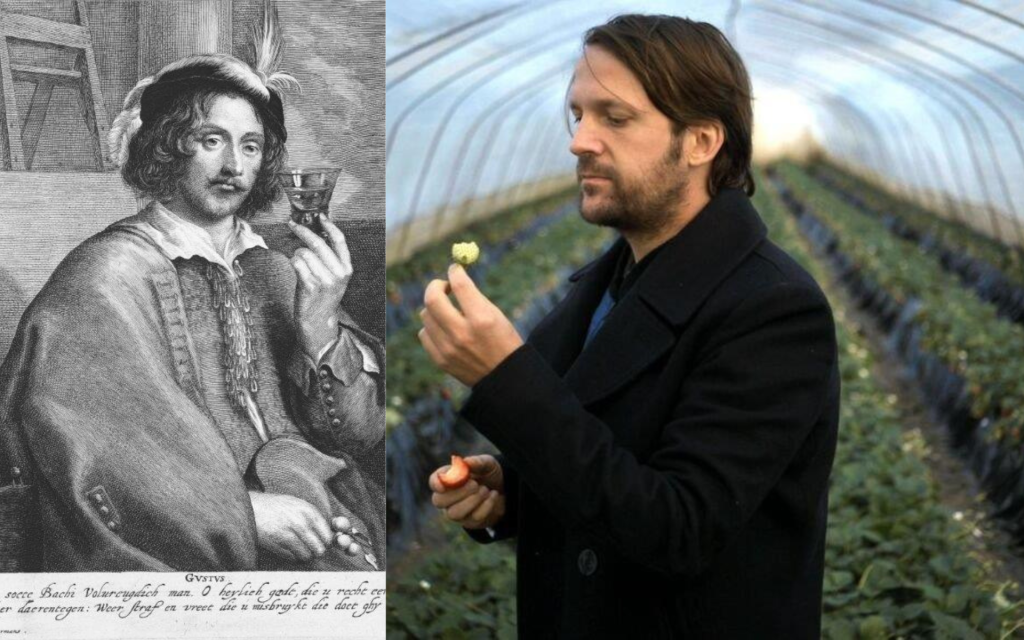

Fast forward a few centuries, and in his cookbook and diary series A Work in Progress, Danish celebrity chef René Redzepi – famous for reinventing and refining new Nordic cuisine at his Noma restaurant – describes how he was inspired by the paintings of artists such as Jan Davidsz de Heem and Willem Kalf. He says of his renowned dish of berries and flowers, served in a beautiful glass bowl, that it captures the same sense of fineness and abundance as the painterly works, with the ingredients’ natural colours and textures its focal point. After Noma closes in 2024, fine diners can only hope Redzepi’s golden age inspirations can be experienced in another three-Michelin-star venture.

Mumbai-based food stylist Swati Desai creates drool-worthy table settings composed to draw in and direct the eye. In this example, a strong diagonal line structures the table layout, formed by the orientation of the table runner, napkin and spoon. The lustrous surface of the metal dishes is emphasised by the lighting, and the separation of foods and items allows the eye to roam freely. Sound familiar? Desai’s considered styling heightens the appeal of the meal, using techniques that nod to the early Old Masters.

When does precise food styling turn into visual obsession? Old Master Adriaen Coorte is still admired today as both a food fetishist and specialised painter. At a glance, his uncommon ability to depict individual vegetables in exquisite detail and light is indistinguishable from the high-pixel images shot by some of today’s most accomplished food photographers.

Linda Lomelino is a Swedish food writer, stylist and founder of Call Me Cupcake sweet food and photography. Her work shows direct respect for the Old Masters, taking many lessons from their playbook. In this example, the tonal table and muted palette highlight the sculptural cake against a darkened background; wisps of candle smoke ascend into a generous framing space, drawing in the viewer’s eye and symbolising the transience of life. And the just-vacated table reminds us that life is short and we should savour every moment – preferably with cake!

Read: fruits, flowers and a psychoscape

Revered for their exquisite attention to detail and stunning realism, the Old Masters’ still lifes were originally painted as a celebration of wealth and abundance, the visual motifs of which occasionally warned against overindulgence and signalled the brevity of earthly life. There’s little risk of today’s food photographers, stylists, celebrity chefs and influencers warning against overindulgence; they elevate food and dining to an art form and their images routinely stimulate eye and appetite alike.

While the Old Masters depicted appealing foods of the time, their paintings also help frame contemporary visual perspectives on food culture and offer a lens through which this may be examined. The golden age may even help us see food culture in a new light.

Read: Local Remix: Still Life