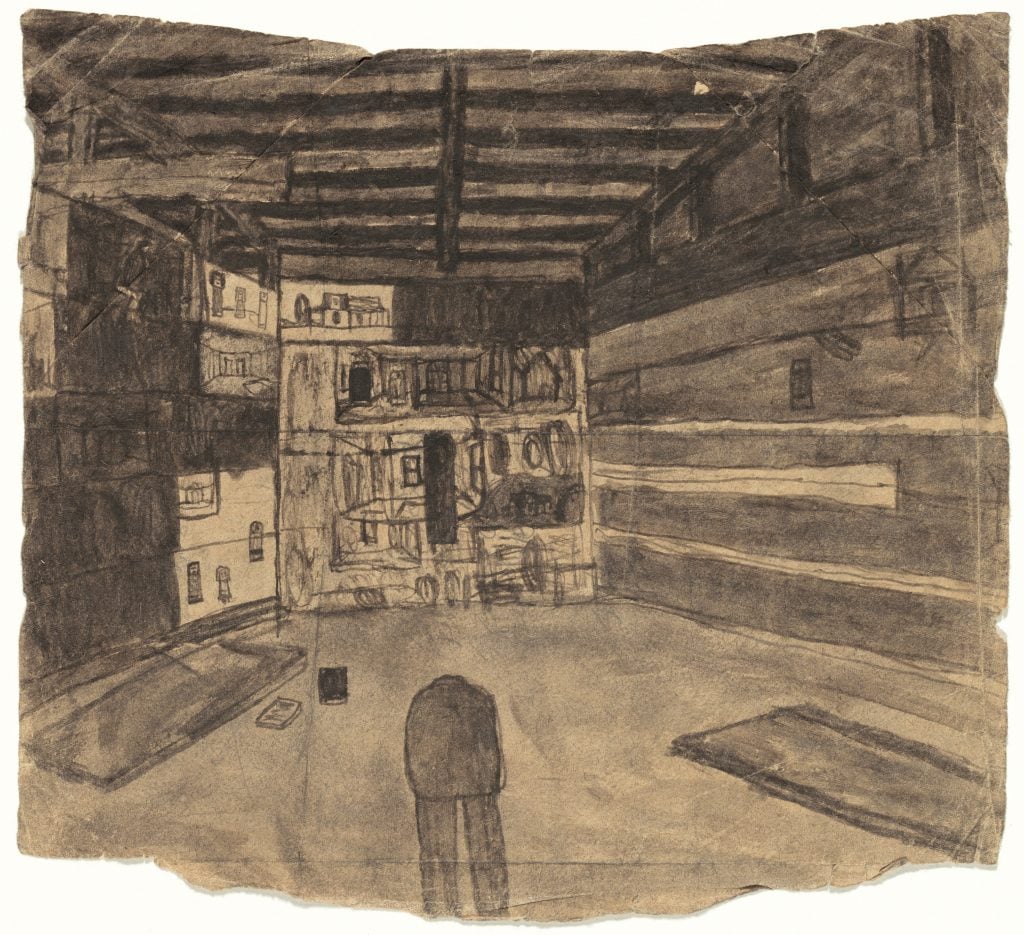

James Castle, Untitled (Shed Interior with Pictures on Display)

National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.

Chosen by: Lynne Cooke, senior curator, modern and contemporary art

What we’re looking at is a small drawing that shows the interior of a barn. On the walls there appear to be pictures, and high on the rafters there’s a row of birds. These pictures and assemblage sculptures are works that James Castle made over a period of time in seclusion and then imagined showing in an exhibition.

The barn was part of the farm he grew up on outside of Boise, Idaho, in the early 20th century. He lived a reclusive life. As an artist, he was self-taught in a very literal sense; there was no one around to teach him. With his family’s support, he drew over a period of nearly 70 years, almost daily. It was a lifelong commitment. Much of what he drew was his immediate surroundings: the house, its interior, people, birds, and the landscape. The gray wash was made from mixing spit with soot from a woodburning stove. He applied this with a stiff instrument, such as a matchstick—a technique he devised himself.

Remarkably, the drawings are made from memory. Castle has an extraordinary ability to render perspective and give you a sense of interiors. I don’t know of many examples where others have made such sensitive and beautiful works, with techniques they’ve invented, that conjure a world as fully as he did.

James Castle, Untitled (Shed Interior with Pictures on Display) (recto). National Gallery of Art, Washington. © 2011 James Castle Collection and Archive LP. All Rights Reserved.

We think that Castle put these shows on in his barn, but no one ever saw them. It’s possible that they occurred only in his imagination. I find it very poignant and moving that he made exhibitions in anticipation of an audience rather than for an audience. There is an added charge when one understands that Castle was born deaf, and he never learned to sign. He never communicated through language with other people. Yet he wasn’t isolated. He lived with his family and sought to communicate through his art. Look at the figure he draws from behind, with the head bent down. I take it to be a shadow of the artist himself, on the threshold, somehow, looking into the space of his creation.

—Lynne Cooke, National Gallery of Art senior curator, department of modern and contemporary art, as told to Zack Hatfield.

What artwork hangs across from Mona Lisa? What lies downstairs from Van Gogh’s Sunflowers? In The Permanent Collection, we journey to museums around the globe, illuminating hidden gems and sharing stories behind artworks that often lie beyond the spotlight.

Follow Artnet News on Facebook: