My dad Elliot Miller was ripped off. Desperate to provide for his family as a poor artist, he sold a painting called Father’s Love—and all of its rights—to a corporation that went on to make millions in reprints. This led to years of struggles as the company profited and he fell deeper into debt and poverty.

All of this occurred before artificial intelligence was ever a force in the art market. Now, with AI, this practice has been institutionalized on a mass scale, nullifying intellectual property rights for artists, culling from a vast sea of their work without attribution, effectively putting them out of work.

Today, my dad also has dementia, which means that he’s losing his ability to create art. AI, it would seem, has taken the place of the same corporate bigwigs who fleeced him since the beginning. Only this time, he’s fighting against his mind and the man.

Over the years, dealers and retailers have stolen millions of dollars-worth of Dad’s pieces—and that’s not including the distributor who made over $10 million on his work. I even met a Black artist whose career got started by working for the distributor who sent lithographs of Father’s Love, Dad’s most famous work, overseas. The rights to this picture were sold, in their entirety, by a naïve young father just trying to keep food on the table for his family. What makes the painting, and my father, even more impactful to me is his love.

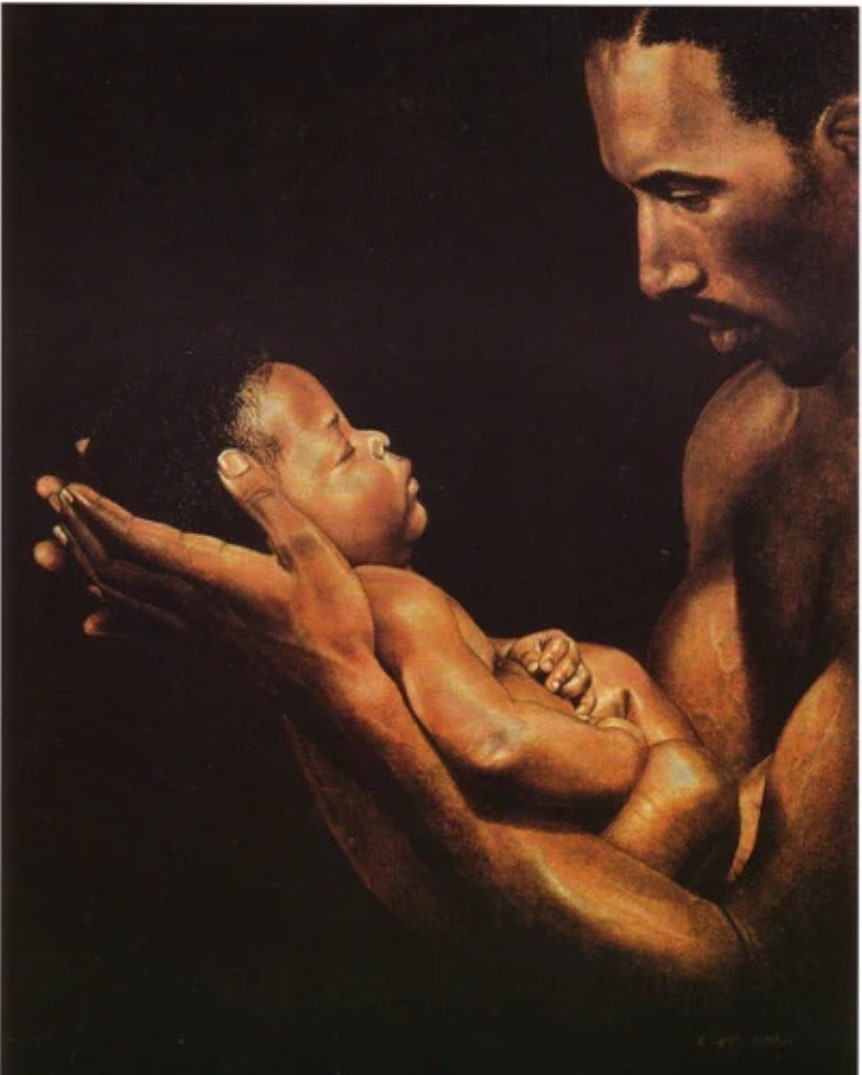

Father’s Love by Elliot Miller.

Courtesy of Alex Miller

Father’s Love, isn’t a complicated picture to understand: A Black man holds his child, head in hands, feet within his forearms, in front of a background as dark as midnight. The little boy stares into the eyes of his protector, somehow knowing who he is. His father stares back, knowing he’d do anything for his child. The tone of the man’s skin is mixed, weathered, a little beaten. It’s a wise and textured blend of browns. The baby is one solid glow of ebony because he hasn’t experienced life yet.

When it was released in the early-to-mid 1990s, Black art blew up like a balloon with a grenade in it. It was something everyone wanted and something everyone wanted to cash in on. Artists like Charles Bibbs, Wak, and Larry Poncho Brown were some of the more famous geniuses of the craft I remember from my childhood.

Unfortunately for my dad and the rest of us, he could never just paint or draw. He’d work three or four jobs and then be an artist when he could. Selling artwork he’d spent days or weeks on for $50 just to keep the lights on sometimes.

Father’s Love was Dad’s magnum opus because he put his life into it. All of his love for the work that often didn’t love him back. The love he wished his father had given him. The struggle of a Black man in the Jim Crow south of Missouri, where his father and grandfather were preachers and it was unthinkable for a “colored” man to be an artist. That painting meant the world to me, as a kid.

That’s why I take such an issue with so-called AI art.

“Look at my latest piece,” my friend wrote in a Facebook post, referring to his DALL-E-generated portrait: a beautiful landscape complete with mountains, winding river, trees, and birds in flight. While my father begins to struggle with his art due to dementia, AI image generators keep making “art” at the touch of a button. While international courts are determining how much a piece of art can be considered original if it’s not created by a human, my dad can’t complete most of his pictures, as he often forgets he’s working on a project before moving onto another one.

As the practice gets easier and more refined, and just about anyone can create AI artwork with the right prompts, the idea of skill and mastery in artwork becomes more of a thing of the past. That might be fine for the bottom line of Big Tech companies looking to cash in on the technology, but the artists of today are suffering for it.

Writers are outraged that nearly 200,000 of their books have been used to train AI chatbots without permission. It’s spurred a summer of strikes from the Writers Guild of America and the Screen Actors Guild. And all for good reason: Along with potentially taking their jobs, research has even suggested that continuously training on synthetic data can create biases and outright hallucinations

As the AI art world rips off artists without their consent through a massive database of artists’ work from the internet, the revelation that so many like my father never got a fair shake becomes more glaring. Artists can struggle their entire lives to make it in their craft—only to see it taken to train art generators like DALL-E or Lensa. It’s getting so bad that people are creating software to tell the difference.

Elliot Miller (L) and his son Alex Miller.

Courtesy of Alex Miller

Luckily, most AI art is easy to spot. But what happens when no device or software can tell the difference between what humans have done and what machine has done?

I fear that the stories that should be told will no longer be told by humans. With AI now threatening writers’ rooms and the news cycle, this fear is quickly becoming a reality. Yet the humanity you experience when you connect with creative work is something AI cannot give or receive.

As a professional writer, I do recognize the impact I’ve had on many readers. My father had that kind of impact too. He’s done work for some very impressive people, and I’ve seen grown men cry when he’s unveiled a portrait of a recently deceased mother or father. However, none of that quite seems to matter right now with the onslaught of emerging technology like AI.

I don’t want to be in my seventies and eighties and unable to afford to pay for my own mental health or a spot in a nursing home because AI replaced me and my craft. Perhaps that’s my biggest fear: That the technology meant to make our lives better will doom me and all other creatives to obscurity.

More than that, my heart is broken for the artists like my father who never got the exposure that AI continues to get. I fear the harshest punishment this universe gave my family was my father’s gift, only for him never to have made enough money or recognition from it, while he spirals into dementia. Some of my favorite memories of my dad are the moments we spent talking about everything and nothing, him drawing and painting in his artist chair and I writing next to him on the floor. We bonded through our shared love of the art we shared.

And now, AI makes those memories ever harder to swallow. Maybe our art goes the way of the dinosaur, as AI just takes what has already been crafted and uses it to produce a heartless facsimile of something a real artist can. That’s a fear that keeps me up at night.

This story was supported by the journalism non-profit the Economic Hardship Reporting Project.