Steven Schmid “All Tooth 9” (2024) Acrylic, Assemblage, Colouring Pencils, Image Transfer on Handmade Paper.

Steven Schmid “All Tooth 9” (2024) Acrylic, Assemblage, Colouring Pencils, Image Transfer on Handmade Paper.

By BYRON ARMSTRONG April 18, 2024

Steven Schmid is a Bahamian artist living in Toronto whose work employs cardboard, digital painting and drawing, handmade painting and drawing, photography, and self-made, repurposed, and upcycled paper. If that seems like a lot, it’s because it is. Nobody will be calling Schmid a lazy artist with tired or derivative ideas.

Schmid’s work attempts to play with concrete ideas of masculinity with a process heavily influenced by Hip-hop’s bling era and the sampling ethos that accompanied it, Bahamian standards of maleness based on Judeo-Christian dogma, and, although you’ll never find this in any artist statement, his mom’s home cooking. He’s exhibited work in the Bahamas at TERN, The National Art Gallery of The Bahamas, and Baha Mar’s “The Current” Gallery and Art Center. A chance encounter with the gallerist and artist consultant Belinda Chun at an OCADU grad show led to his current show “I am here are you” at Gallery House from April 6th to May 1st.

I spoke to Schmid in his studio a few days before his latest opening, and we talked about his background, process, influences, and the alt-right weirdness of petro-masculinity (yes, that’s a thing).

Who is Steven Schmid, and what has your journey in the art world been like up to this point?

I’m an artist from the Bahamas. I’ve been making art for around 14 years but only started calling myself an artist a few years ago. I find a lot of responsibility in that word, so even after I went off to art school and was doing work and was very active, it took a while to feel like I’d earned that stripe. I was interested in marine biology for a long time and used to work as an aquarist taking care of marine life in aquariums in the Bahamas. I would do little drawings and doodle and knew I was good at art but even in art school, I was thinking I was still going to be an underwater videographer. I think after my first class, I really got into painting, then a love of art in general. I just went all in on it and have been painting and drawing ever since.

How did this show at Gallery House happen, and what has preparing for this show been like for you?

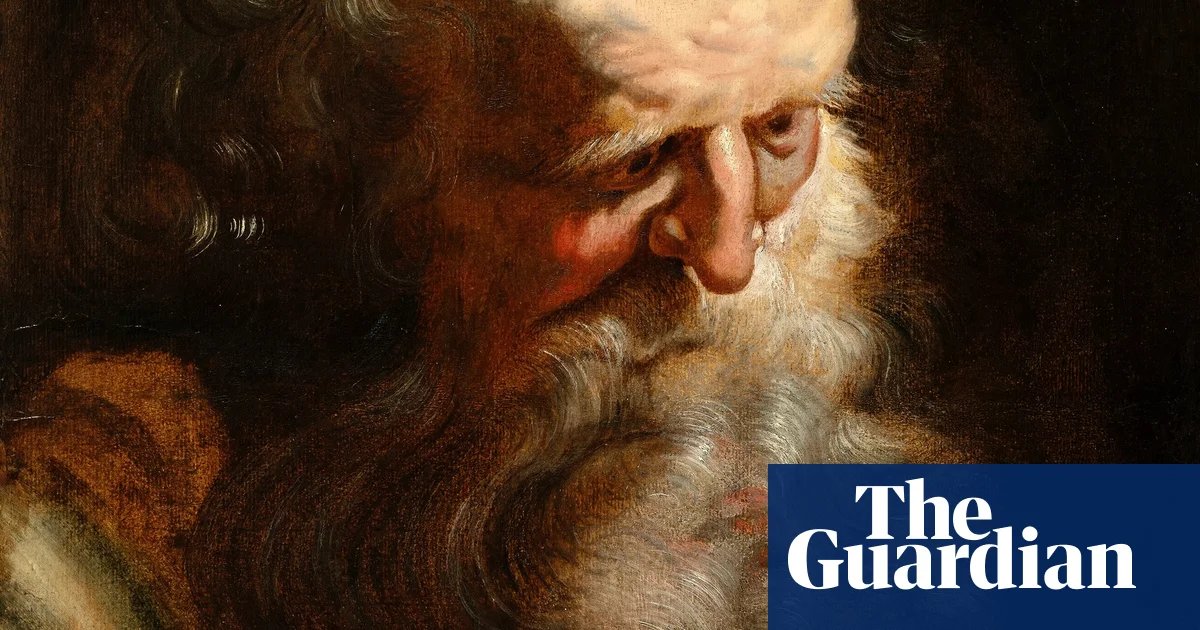

I met the gallery owner and curator, Belinda Chun , at my grad show at OCAD University. We were sharing emails back and forth and had a couple of studio visits up to last year when she asked me to show in her gallery. A lot of the work that I did for the show was almost an extension of another show that I did last October called “Showin Teeth” in The Bahamas (The Current – Baha Mar Gallery). That was the first series of artwork using handmade, upcycled paper, which is a process I started last summer while researching paper-making and photo transferring. So within this new series is some work from past series “All Put Together” “This Must Be Place” and “All Teeth” – an extension of the series in Nassau – which is this close-up of a mouth that amalgamates a lot of my family members’ smiles in the work. So there are nine pieces in total in the show.

Steven Schmid “All Put Together 3” (2024) Acrylic, Assemblage, Colouring Pencils, Image Transfer on Handmade Paper

Steven Schmid “All Put Together 3” (2024) Acrylic, Assemblage, Colouring Pencils, Image Transfer on Handmade Paper

It’s hard enough to make one medium or material work as an artist. Why did you want to go through the extra process of incorporating digital, paint, and collage in your work, and how do you do it exactly?

In the Bahamas, I could hand paint and draw images wherever and then collage them. Living through COVID-19 in an apartment in Toronto, the space confinements led me to work digitally. That’s how many of these works started. In late 2020 I made a 100% digital piece but I felt like something tangible was missing. The Bahamas can be perceived as being part of the Caribbean by Americans and at the same time considered more American than the Caribbean by other islands. That idea of existing in an intermediary space influenced my work in the sense that using the digital space combined with a lot of different stuff — cardboard sculptures, family photographs, and digital or physical drawings — that space is where everything can kind of coexist together. I would make digital paintings, physical paintings, and drawings, then print out works on a printer. I would photograph the lines in it, add that back into the work, make cardboard sculptures from those little printouts, and then photograph that and add that back into the work. I started projecting onto the sculptures and photographing them to add to the work. Thinking about an intermediary space, and having a spot where all those ideas could come together and communicate became very important to me. I would say it was very organic. I’ve realized I don’t have to leave my space to create work, and in fact, there were a lot of things I could do, like making my own paper, without outside help.

Steven Schmid “This Must be the Place 6”, (2024) Acrylic, Assemblage, Colouring Pencils, Image Transfer on Handmade Paper

Steven Schmid “This Must be the Place 6”, (2024) Acrylic, Assemblage, Colouring Pencils, Image Transfer on Handmade Paper

How do the politics of masculinity in The Bahamas and your personal experience with that inspire your artwork?

I think the biggest thing for me is the intersection of hip-hop and religion, and how that kind of ties into representations of masculinity on the islands. The idea of being the head of the household, and how the presentation of masculinity and the performance of it, pulls a lot from Hip-hop culture during the mid to late-90s and early-2000s, and Judeo-Christian representations of male roles. With Hip-hop, there are still all kinds of ostentatious representations of masculinity — a lot of jewelry and gold grills. But that previous era was when tons of money began flowing into the genre, and much of that display was very in your face. I’m interested in the documentation of when a guy wants to have their photo taken and the posturing that results. I wondered what would happen if I documented those moments just before or after the photo was taken, which is usually when guys drop the hard ‘ice grill’ facade and are usually just themselves, laughing or joking around. I think about how deep-rooted some of these ideas about masculinity are, and how hard it is to kind of untie them. As I’m doing work, I’m examining those ideas visually, through the actual image, but also the artmaking process as well. So if you look at the work you’ll see a lot of things happening, like how Hip-hop songs used a lot of music samples — mixing, blending, and overlapping. Images overlapping that may seem contradictory. It explores how you almost have to work within the confines of an original image to make something new out of it.

With religion, I’m thinking about hierarchical standards. Just even the basic “man as the head of the household” and “women must submit” to his leadership. I’m trying to strip all that to allow for the idea that just being yourself is enough without all the hierarchies.

Individuality is another theme in your work. So as a Bahamian male artist drawing on your personal experiences, how important is having a sense of identity to express your individuality in your art and life?

I think one of the most important things for an artist is honesty, which sometimes means giving up a lot of old beliefs and accepting different ideas. You have to realize that something you’ve believed for 20 or 30 years may require X amount of time to unlearn, unravel, or reinterpret so you can make something new out of it. With every decision I make visually within the work, or even just my ideas, I try to accept what comes creatively. That tends to lead to an easier trajectory when I stop fighting any perceived faults in the work and just let it flow and happen. I think most of that comes from my mother. Cooking is her love language and she’s very versatile in that way. She’s Bahamian but lived in Germany with my dad for several years, so she would cook an almost fusion-style meal. Not having a lot of money also makes you more resourceful. She’s the kind of person who would try a dish, and if it didn’t work out, she would turn it into something else. She made a mish-mash sort of dish with a bunch of different ingredients and loved it. So alongside the influence of Hip-hop and sampling, there was my mom’s cooking and resourcefulness.

Steven Schmid in his studio, Toronto, Canada (2024)

Steven Schmid in his studio, Toronto, Canada (2024)

There’s a phenomenon called “petro-masculinity” anchored in alt-right movements, where any discussion of climate change and renewable energy is considered a threat to traditional manhood since men traditionally dominated those jobs — working on an oil rig or coal mining for instance. Meanwhile, your work explores the complexities of manhood by upcycling materials and making paper from scratch. How do you think your work upends that way of thinking about sustainability and masculinity?

When I began exploring the papermaking process and photo transferring online, practically all of the people doing it were older women artists using their immediate surroundings to make beautiful things. A lot of my practice is based on intersectional feminism. I was reading a lot of bell hooks and ideas around breaking down masculinity to a place where it’s not based on your gender so much as your personhood. Much of my values as a person and artist are based on the teachings of a lot of women, including intersectional feminism. I connect with ideas of breaking down hierarchies and also using things that are immediately around you. So I think the concept of petro-masculinity is actually kind of funny because it is such a ‘we deserve this space so it has to exist this way’ mentality you know? ‘The Lord intended it to be like this, even if it means the end of the world.’ So even within my work, I like the idea that it’s okay to break down something you believe is supposed to be permanent and restructure it.

Steven Schmid “I am here are you” shows April 6th through May 1st at Gallery House (2068 Dundas Street West, Toronto). WM