The sculptor, goldsmith and murderer Benvenuto Cellini found himself alone one day on a Florentine piazza facing his rival Baccio Bandinelli, whose statues he thought looked like sacks of squashes topped by melons for heads. He fingered his dagger, getting ready to deliver the ultimate killer review. Then he took pity on this pathetic figure sitting on a donkey and stayed his hand.

The Royal Collection, too, has compassion for Bandinelli. It includes him in this often tremendous if slightly baggy show from its huge holdings of Italian Renaissance drawings, alongside Raphael, Michelangelo and Leonardo da Vinci. You see immediately why his sculptures are so terrible, for in a section with some of the greatest nudes ever sketched, Bandinelli’s study of a posing male figure has still got his clothes on. No wonder his hulking statues lack anatomical conviction.

Michelangelo did not have that problem. His black chalk drawing of The Risen Christ is a male nude leaping from the grave, arms flung up, his muscles flowing with energy, rippling with joyful resurrected life. Short of giving the son of God an erection Michelangelo could not have put more vitality into his naked form. He is content to precisely delineate the Lord’s unrisen penis on sagging balls.

The close knowledge of human anatomy underpinning this thrilling holy nude is illuminated by rangy dissection drawings that Michelangelo did in about 1520. These examinations of the muscles and tendons of a flayed human leg prove Leonardo was not the only Renaissance artist ready to spend his nights among dissected corpses.

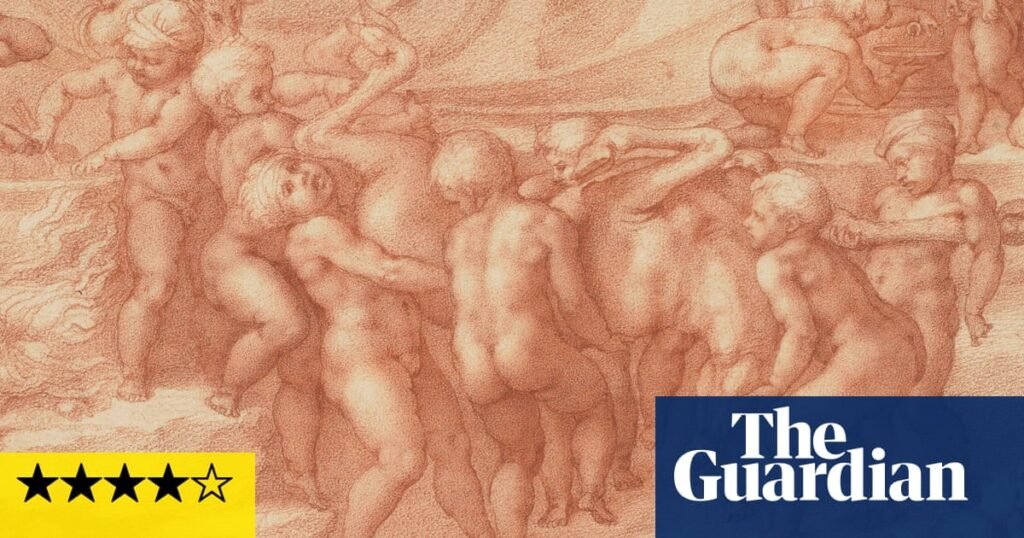

This exhibition takes you under the skin of the Renaissance. It is intimate and unabashed. Next to Michelangelo’s red chalk drawing A Children’s Bacchanal, curator Martin Clayton’s wall text explains forthrightly that: “In 1532 Michelangelo fell in love with the young Roman nobleman Tommaso dei Cavalieri”, and gave him this fine present. Only a few months ago a British Museum show talked coyly about Michelangelo’s “friendship” with Tommaso.

There’s a real desire here not just to show off the Royal Collection but use it to inspire drawing now. Charles III is known for his support for drawing as a living art: the Royal Drawing School, which he founded 24 years ago, is a genuine force for creativity. When I visited the exhibition, artists were already there, copying and learning.

There is plenty worth their time. The most intimate moment is Raphael’s drawing in lush red chalk of one naked woman in three poses as she models for a fresco of the Three Graces in the Villa Farnesina in Rome. Raphael’s drawing has a gentle eye for her self-consciousness, and the electric feeling of being directly drawn from life. Could this be the woman who, according to the 16th-century writer Vasari, Raphael was so in love with he was too distracted to do his frescoes? The villa’s owner, claims Vasari, had to let her live there to get him to concentrate. This looks for all the world like she’s posing for the besotted artist.

We get closer here to Raphael or Michelangelo as living, loving people, but they are still giant enigmas whose skill at drawing no one may ever possess again. After all, we don’t select the most talented kids and make them full-time artistic apprentices at 13, doing nothing but draw. A sweet, anonymous sketch at the start of the show depicts a Florentine youth absorbed in drawing while the workshop dog takes a nap in the corner.

But not every artist produced by this system was a Raphael. The varying talent levels of Renaissance artists revealed here offer inspiration to anyone who wants to draw. Bandinelli is not so intimidating and you meet a whole host of, let’s say, less brightly burning stars.

after newsletter promotion

It is like visiting an Italian church and seeing so-so pictures in dimly lit side chapels: oddly comforting. Many of these drawings connect you to places in Italy, where the frescoes or oil paintings for which they are designs still exist in palazzi or churches. That is not just true of the minor artists. There’s a great drawing, surely from life, of a woman with a square, serious face by Michelangelo’s teacher, Domenico Ghirlandaio; she made it into his fresco of The Birth of the Virgin in the church of Santa Maria Novella, Florence.

Italy comes even closer when you look at Leonardo’s map of Tuscany which, instead of his usual scrawled mirror-writing, has place names capitalised and the right way round. It is neatly coloured with lakes and rivers in blue – a working map to show to officials when he was working as a hydraulic engineer for the Florentine Republic.

Let’s be honest. Leonardo is in an exhibition of his own. The Royal Collection has the greatest holdings on Earth of drawings by the man from Vinci. It tries its hardest to see him here as just one of the Florentine kids who learned to draw as teenaged apprentices: a lily probably drawn by his master Verrocchio shows the calibre of his teacher. Don’t just stick with Leonardo, the show implores, give the other artists their due.

Fat chance. The dazzling permutations of Leonardo’s mind explode out of time. One sheet is covered with faces in an endless, ecstatic observation of human variety: young women, old men, angry stares – it could be animation. In another drawing the elderly Leonardo watches his cats play, fight, and play-fight in oscillating flurries of motion. A drawing of a bird’s skeletal wing takes us into his lifelong fascination with flight.

A lot of churches got frescoed but Leonardo flies above them all.