Career

Upon graduating from the Art Institute in 1918, Motley took odd jobs to support himself while he made art. An idealist, he was influenced by the writings of Black reformer and sociologist W.E.B. Du Bois and Harlem Renaissance leader Alain Locke and believed that art could help to end racial prejudice. At the same time, he recognized that African American artists were overlooked and undersupported, and he was compelled to write “The Negro in Art,” an essay on the limitations placed on Black artists that was printed in the July 6, 1918, edition of the influential Chicago Defender, a newspaper by and for African Americans. The long and violent Chicago race riot of 1919, though it postdated his article, likely strengthened his convictions.

Britannica Quiz

Can You Match These Lesser-Known Paintings to Their Artists?

In the 1920s he began painting primarily portraits, and he produced some of his best-known works during that period, including Woman Peeling Apples (1924), a portrait of his grandmother called Mending Socks (1924), and Old Snuff Dipper (1928). He also participated in “The Twenty-fifth Annual Exhibition by Artists of Chicago and Vicinity” (1921), the first of many Art Institute of Chicago group exhibitions he participated in. In 1924 Motley married Edith Granzo, a white woman he had dated in secret during high school. In 1928 Motley had a solo exhibition at the New Gallery in New York City, an important milestone in any artist’s career but particularly so for an African American artist in the early 20th century. That same year for his painting The Octoroon Girl (1925), he received the Harmon Foundation gold medal in fine arts, which included a $400 award. (The Harmon Foundation was established in 1922 by white real-estate developer William E. Harmon and was one of the first to recognize African American achievements, particularly in the arts and in the work emerging from the Harlem Renaissance movement.) In 1926 Motley received a Guggenheim fellowship, which funded a yearlong stay in Paris. There he created Jockey Club (1929) and Blues (1929), two notable works portraying groups of expatriates enjoying the Paris nightlife. In 1932 Motley contributed two paintings—Portrait of My Mother (c. 1930) and Brown Girl After the Bath (1931)—to the “Thirty-sixth Annual Exhibition by Artists of Chicago and Vicinity” at the Art Institute of Chicago.

Himself of mixed ancestry (including African American, European, Creole, and Native American) and light-skinned, Motley was inherently interested in skin tone. He generated a distinct painting style in which his subjects and their surrounding environment possess a soft airbrushed aesthetic. It was with this technique that he began to examine the diversity he saw in the African American skin tone. His series of portraits of women of mixed descent bore the titles The Mulatress (1924), The Octoroon Girl (1925), and The Quadroon (1927), identifying, as American society did, what quantity of their blood was African. He viewed that work in part as scientific in nature, because his portraits revealed skin tone as a signifier of identity, race, and class. In those paintings he was certainly equating lighter skin tone with privilege. His portraits of darker-skinned women, such as Woman Peeling Apples, exhibit none of the finery of the Creole women. Motley’s intent in creating those images was at least in part to refute the pervasive cultural perception of homogeneity across the African American community.

Beginning in 1935, during the Great Depression, Motley’s work was subsidized by the Works Progress Administration of the U.S. government. He also participated in the Mural Division of the Illinois Federal Arts Project, for which he produced the mural Stagecoach and Mail (1937) in the post office in Wood River, Illinois. In the late 1930s Motley began frequenting the center of African American life in Chicago, the Bronzeville neighborhood on the South Side, also called the “Black Belt.” The bustling cultural life he found there inspired numerous multifigure paintings of lively jazz and cabaret nightclubs and dance halls. As Motley’s human figures became more abstract, his use of color exploded into high-contrast displays of bright pinks, yellows, and reds against blacks and dark blues, especially in his night scenes, which became a favorite motif. Notable works depicting Bronzeville from that period include Barbecue (1934) and Black Belt (1934).

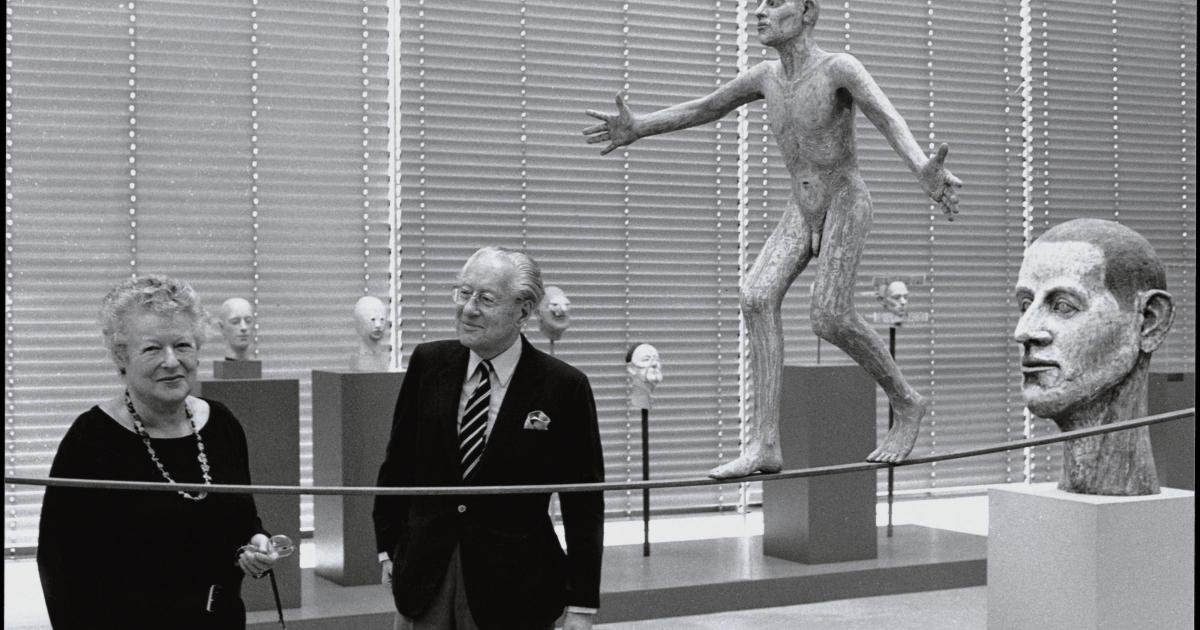

After Motley’s wife died in 1948, he stopped painting for eight years, working instead at a company that manufactured hand-painted shower curtains. During the 1950s he traveled to Mexico several times to visit his nephew (reared as his brother), writer Willard Motley (Knock on Any Door, 1947; Let No Man Write My Epitaph, 1957). While in Mexico on one of those visits, Archibald eventually returned to making art, and he created several paintings inspired by the Mexican people and landscape, such as Jose with Serape and Another Mexican Baby (both 1953). Though Motley’s artistic production slowed significantly as he aged (he painted his last canvas in 1972), his work was celebrated in several exhibitions before he died, and the Public Broadcasting Service produced the documentary The Last Leaf: A Profile of Archibald Motley (1971). After his death scholarly interest in his life and work revived; in 2014 he was the subject of a large-scale traveling retrospective, Archibald Motley: Jazz Age Modernist, originating at the Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina.