Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

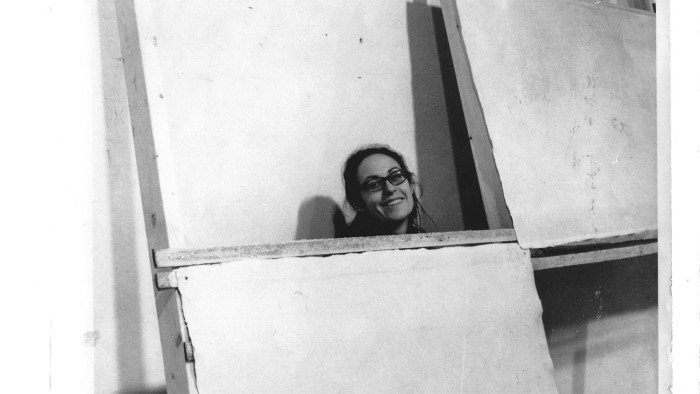

Roll up the door on the old fire station in Linlithgo, upstate New York, just east of the Hudson River, and you’ll find quite a surprise within. No truck, no fire hoses, but instead sculptures hanging from the ceiling, with tools and parts of other artworks scattered everywhere. For 20 or so years, this has been the studio of the artist Alice Adams. It’s an out-of-the-way place and, for a while now, she’s been mostly out of view herself. This year has been different. First, Adams was featured in an exhibition at London’s Courtauld Gallery, in equal billing with Louise Bourgeois and Eva Hesse. Now she has a solo presentation with Zürcher Gallery at Frieze Masters. It’s the “better late than never” syndrome that frequently afflicts women artists, and Adams is an extreme case: she’ll be 95 years old in November.

This isn’t the first time the art world has beaten a path to her door. Raised in Queens, Adams graduated from the painting programme at Columbia University in 1953, a classmate of Donald Judd’s. She then received a grant to travel to Aubusson, the historic centre for French tapestry. While she’d had no previous experience with the medium, she found it immediately intuitive — “the simplest kind of weaving, one up, one across” — and started working in textile. Her timing was perfect. Experimental fibre art was just then taking off, and Adams was more experimental than most. One early work, from 1959, incorporated the head of a dust mop, anticipating the later feminist art movement. She parodied patriotic militarism in “The Major General” (1962), just as American involvement in Vietnam was getting under way.

“The Major General” was one of two works by Adams included in Woven Forms, a groundbreaking exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Crafts in New York (today the Museum of Arts and Design), which also introduced luminaries of fibre art such as Lenore Tawney and Sheila Hicks. Adams also began writing for the magazine Craft Horizons, then adventurously edited by Rose Slivka.

At the same time, though, she was circulating within avant-garde circles (her brother-in-law was the pop artist James Rosenquist). She had always meant to be an artist, not a weaver, and in those days that distinction was widely enforced. Soon after Woven Forms she decided to abandon her loom, taking up materials like wire, foam and latex. When she had her next gallery show, Adams asked Slivka not to have it reviewed, effectively cutting her ties to the craft world.

Today Adams says that she feels badly about that decision, but at the time it was probably a good career move. In 1966, Lucy Lippard, one of New York’s most influential curators, included her in another bellwether show, Eccentric Abstraction, which moved away from hard-edged minimalism in favour of softer process-based forms. The Courtauld exhibition held earlier this year, Abstract Erotic, revisited that moment by gathering the three women who were in Lippard’s show. Even in the illustrious company of Bourgeois and Hesse, Adams’ work impressed. Looming over the proceedings was “Big Aluminum 2” (1965), a twisting volume of chain link fence. “Resin Corner Pieces” (1967) consists of several layers of paint on to wire lath, making hardened brushstrokes that lean against the wall. “Pleated Sculpture” (1969) combines a ruffle of fine metal mesh with a thin coat of latex. Textile thinking is evident in these works — an orientation to the grid, a tension between structure and pliability — but their ghostly beauty is also very much akin to Hesse’s contemporaneous sculptures, as well as those of later figures like Rachel Whiteread.

Adams’s work was uncompromisingly non-commercial, but she was not too concerned — there wasn’t much money in the art world anyway, back then. And she was at the very centre of things, with a studio on the Bowery in downtown Manhattan. Nearby, she co-founded a co-operative gallery called 55 Mercer, where she created site-specific work so subtle that it came close “to being confused with its setting”, as Artforum noted in one positive review. Further recognition came with her inclusion in the 1973 Whitney Biennial.

Adams was not one to stay put, though. She got off the wall, making assemblages that look like fragments of old buildings, unsheathed and released into the wild. Some sport arches that suddenly stop halfway up, as if gesturing to some larger invisible structure. In 1977, she realised the haunting “Adams’s House”, a partial recreation of her own childhood home, on the grounds of the Nassau County Museum in Long Island. A few walls and doorways were sketched in upright timber framing, and there was cross-bracing for a floor — but no actual floorboards. The whole structure petered out in mid-air: an affecting portrait of memory, partially reconstructed.

The last chapter in Adams’s career has seen her embark on a series of commissions for transit stations, parks and university campuses. As is often the way with public art, some of these remained unbuilt, while others have not survived. Meanwhile, many of her early textiles and fragile sculptures of the 1960s were also lost, while “Adams’s House” and related projects were always meant to be temporary. This is one reason for her relative obscurity — the other being the disrespect that all women artists of her generation faced. Seven decades into her career, though, she’s still at it, working in her Linlithgo studio. Adams has been many things: weaver, writer, sculptor, one of the last living links to the rough-and-tumble art scene of 1960s New York. She’s a shape-shifter, and above all, a survivor.

Find out about our latest stories first — follow FT Weekend on Instagram, Bluesky and X, and sign up to receive the FT Weekend newsletter every Saturday morning