Daria Khozai is a Ukrainian interdisciplinary artist and architect who has been based out of Amsterdam for 8 years. Along with her installations, she is simultaneously conducting self-initiated research on traumatic memory at the Amsterdam Medical Center Department of Psychiatry. Her unique triad of disciplines have resulted in the fusing of craftsmanship, architectural research, and academic psychology, enabling Khozai to analyze the anatomy of individual and collective traumas and their relationship to the built environments they occurred in.

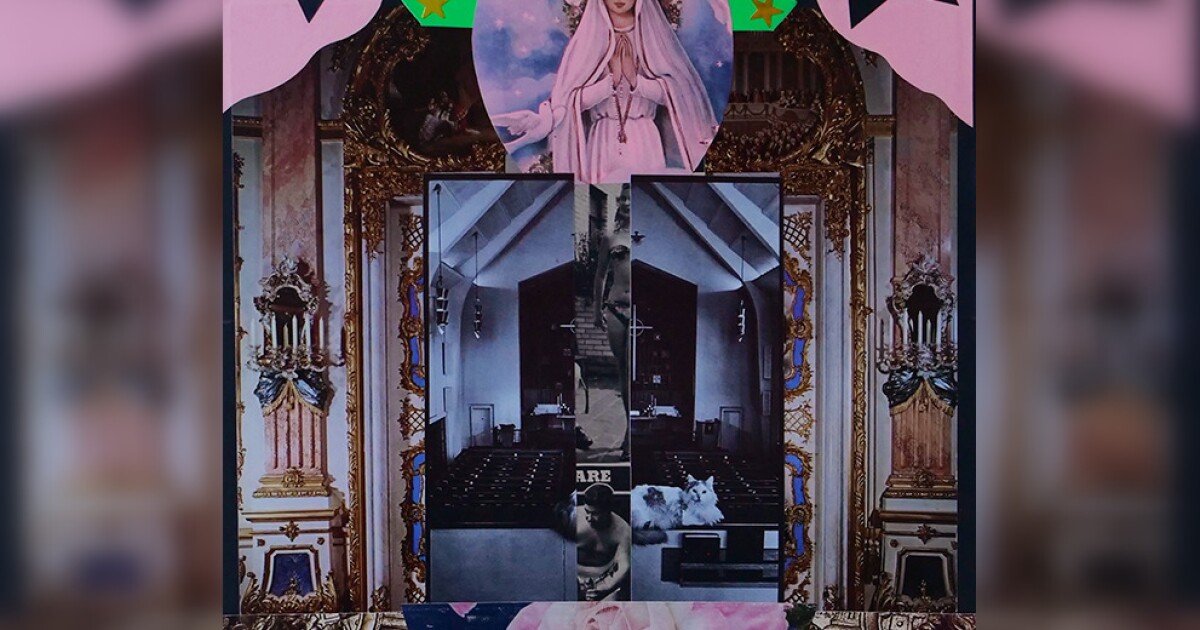

Khozai received the 2025 Galatea Kunstprijs for artists with a refugee background for her installation “If Walls Could Talk”. The installation is inspired by a Sovetskaja Stenka from her childhood home. This iconic cabinet wall full of porcelain, glittering crystal and propaganda books reflected the Soviet ideology of communism, censorship and complete state control. The embalmed mealworms on the installation symbolize the rot from within. Her work, along with that of the four other nominees, can be viewed at the Dordrecht Museum until October 5th.

Khozai sat down with the Dam Yankee Podcast, in partnership with NL Times, this week to discuss the success of her project. She also touched on what home means to her, if she will return to Ukraine, and what is it like to be an artist in the Netherlands.

DY: When the war in Ukraine eventually does come to an end and if there is a call for the diaspora to come home, is that something that you would look towards?

DK: Well, it’s difficult to talk about it like this because today is the fourth of July and it was a horrible night in Kiev. So I, of course, I really feel for it, and I didn’t sleep all night myself. So of course I want to come back, but I want to say, I want to be a bit realistic.

Ukraine has much more problems than just the war. We still have a lot of corruption. I really don’t think this will change anytime soon, even after the war finishes. So I don’t see too many possibilities for myself because I’m trained as a landscape architect. I have a big project that I would love to present there because I know Ukraine more than, for example, Norman Foster Company, who’s to construct something there after the war finishes. I would like to contribute.

But I don’t really see possibilities, at least not during my life. So yeah, I would like to come back. Of course, I would love to do something there professionally, yes. To live there—I don’t think I can fit there anymore or something. I don’t feel welcome there. Also in the professional field, the same like here, the same like anywhere—I feel like in between.

DY: Can you expand on that a little bit more—how you don’t feel welcome when you go back to Ukraine?

DK: Well, first of all, I don’t have too many people who stayed there. So now they are spread all over the world. Of course, I have my mother and my younger brother there. So yeah, of course I’m welcome there, but…

The art field there works a little bit differently. They have their own group of artists that they are really taking care of, and the young artists don’t have really that many opportunities. I also heard it from the artists in the Netherlands that it’s difficult to succeed in the country you’re coming from because people are even more critical to what you do.

I also got comments that, yeah, how can you talk about this problem—you left, you know? But yeah, I didn’t leave because I wanted to. So it’s a bit strange. I also get comments because sometimes I can speak Russian, so I get comments on that as well. But if you comment on my language, how are you different from the Russian person that forbids speaking different languages in the country? We are multinational, and we should respect it also.

It’s a bit controversial, especially now. People united at first and were very supportive. And now it’s kind of the opposite. It feels like everybody’s a bit against each other and even more critical, even more angry. Yeah. It’s a difficult conversation.

DY: That division that you see and those sorts of divides you were just reflecting on—is that something that you’ve also noticed elsewhere as well?

DK: Yes, exactly. So I heard—because I don’t have this experience—but I heard from Dutch artists in the Netherlands that it’s also very difficult to succeed, just because people are more critical. They are more interested to see the stories from outside. And I want to say that I actually don’t mind because everybody in Ukraine knows what’s going on in Ukraine. Okay, my role is to show it here for the people who don’t know enough or don’t pay attention enough—to talk about it. To bring it to the table again.

For example, I was in the Dordecht Museum recently, and there was a group of tourists from the USA. I was really very happy and surprised to see that for them it was just like a touristic location—they just visited a museum. But then it really touched them, because maybe they never thought about migration in this way, from the point of view of the refugee who flees. So it also opened up something for the people who maybe were not even thinking about it before.

All of Daria’s work and happenings can be kept track of on her website. If you’d like to see some of her other work, a 360 replication of her exhibition ‘Pravda’ has been made available to explore online.

Listen to this entire episode of Dam Yankee wherever you get your podcasts, or watch the full videos on YouTube. Daria goes on to explain how she uses art a coping mechanism, why she will never make work for clients, and how so much of her life as an artist is just like any other job.