2025 was so rich in expectation that it seemed unlikely to deliver even a fraction of its many enticing promises. And yet, it really has been a truly vintage year for art – some consolation perhaps for what has in other respects been a mixed bag.

Blockbusters to suit all tastes ranged from cutting edge fashion at the Barbican to Constable & Turner at Tate Britain via an epic celebration of Nigerian Modernism at Tate Modern. On a smaller scale, but with no less pizzazz, were revelatory shows on the formidable, campaigning Chilean photographer Paz Errázuriz, and the little known modernist painters Paule Vézelay, and Ithell Colquhoun.

The Courtauld Gallery continued its run of gorgeous and scholarly boutique shows, and Hampshire Cultural Trust in Winchester staged a small but glorious exhibition of Hans Coper’s lost murals. Dulwich Picture Gallery unveiled its magical new sculpture garden, and sensory play pavilion, and the National Gallery had a not uncontroversial rehang as part of its Sainsbury Wing revamp. These are my picks for the 10 best art exhibitions of the year.

10. Ben Edge: Children of Albion, Fitzrovia Chapel

I’m sorry to say that by the time you read this, Children of Albion, an exhibition by Folk Renaissance pioneer Ben Edge will only just have closed. Optimistic and intelligent, Edge’s reimagining of our ancient shared traditions, reworked through the visual worlds of William Blake and prehistoric land art, Hieronymus Bosch and local folk groups, is a passionate and deeply personal entreaty for community, creativity, and care for our environment and each other. The exhibition centred on Children of Albion, an epic retelling of the history of the British Isles in the jewel-box interior of Fitzrovia Chapel. If you missed it, don’t worry – I bet my hat that 2026 brings more chances to see his work.

9. Wes Anderson: The Archives, Design Museum

There’s absolutely no excuse for neglecting this beautifully curated look inside the world of idiosyncratic auteur Wes Anderson, creator of films from The Grand Budapest Hotel to Fantastic Mr Fox. Just opened at the Design Museum, this is the perfect way to while away a few hours over the Christmas holidays, and has something to placate even the most recalcitrant of family members.

Its film-by-film structure will satisfy movie buffs, but even if you’re not an Anderson devotee, you can’t fail to be beguiled by displays of puppets, miniature sets, props and storyboards. The precision and perfectionism lavished on these productions is inspiring, and with barely a whiff of the digital, it’s a moving love letter to creativity, craft and the power of the imagination. To 26 July 2026, Design Museum, London.

8. Lee Miller, Tate Britain

It was only after her death in 1977 that Anthony Penrose, son of legendary photographer Lee Miller, discovered the truth of his mother’s remarkable career. In the decades since, her role as a lynchpin of the Surrealist movement, and the creator of some of the most unforgettable images of the Second World War, have become clear, culminating last year in Kate Winslet’s star turn in Lee, which shared her story still further.

This exhibition, the biggest and most comprehensive ever staged, has been made with the close co-operation of Miller’s son and granddaughter. With all the famous pictures you can think of, and many more that have never been seen, this is a chance to appreciate Miller anew, in pictures that look better than ever in the flesh. To 15 February 2026, Tate Britain, London.

7. Tirzah Garwood: Beyond Ravilious, Dulwich Picture Gallery

Some of the most memorable and enchanting objects in Dulwich Picture Gallery’s winter exhibition were the doll-sized, three-dimensional collages made by Tirzah Garwood, an artist whose prolific creative talent found any outlet amidst the endless demands of domestic life. She was first and foremost a wood engraver, and her characteristically humorous, beady-eyed observations are a hallmark of the prints of her early career. With a family to look after, she shifted to marbling paper, and became the country’s leading maker; with scrapbooks, embroideries, and costume-making, it kept her creative flame alive. The combined blow of a terminal breast cancer diagnosis and the death of her husband coincided with a final period of strange, surrealist paintings that hint at the artist she might have become had she survived.

6. Mary Kelly: We Don’t Want to Set the World on Fire, Pippy Houldsworth Gallery

Queen of feminist conceptual art, American Mary Kelly reflects and reprises the major themes of her six-decade-long career in an exhibition of new work at Pippy Houldsworth Gallery in Mayfair. Featuring the compressed tumble drier lint that she has been perfecting as a medium for the past 25 years, the exhibition centres on her World on Fire Timeline (2020), described as a coda to decades of the artist’s work, linking global conflicts with her personal story.

Sobering and optimistic, Kelly’s catalogue of disaster measures the power of protest through the filter of a tumble drier, a symbol of domestic, predominantly female, individual action. And if all you can think is how do you make anything sensible from tumble-drier lint, wonder no more – just go! To 24 January 2026, Pippy Houldsworth Gallery, London.

5. Siena: The Rise of Painting, 1300 ‒1350, National Gallery

This is exactly the type of exhibition that the National Gallery was born to stage, and it was no coincidence that this superlative event took place as part of the gallery’s 200th anniversary celebrations. Some of the earliest paintings in the collection, by masters including Simone Martini and Duccio, formed the core of the show, which focused on the intense innovation and creativity that swept through Siena in the early 14th century, spreading far beyond to influence all the art forms in the generations that followed. Spectacular reunions of multi-panel altarpieces, broken up centuries ago, were reunited, including Duccio’s Maestà, the surviving pieces of which were brought together for the first time since the 18th century.

4 Edward Burra, Tate Britain

How is it that this time last year I knew almost nothing about genius watercolourist Edward Burra? In part it’s probably because he couldn’t bear publicity, or talking about “Fart” as he liked to call it; and then chronic poor health meant that he was a virtual recluse by the time he died in 1976. Based on the vast archives entrusted to Tate at his death, this show was nothing short of a revelation – not just because of Burra’s evocative scenes of the Harlem Renaissance, and seedy Paris jazz clubs, or his sinister war pictures. Nobody has ever used watercolour like Burra, before or even really since – he was an exceptional, one-off talent. Now we know him, we won’t forget in a hurry.

3. Wayne Thiebaud: American Still Life, Courtauld Gallery

A feast for the eyes, Wayne Thiebaud’s cakes and pies are a festive treat to rival The Nutcracker’s Land of Sweets. Well known in the US, Thiebaud is much less familiar in Europe, and this is the first exhibition of his work ever staged in a UK museum. For all their sugary appeal, Thiebaud’s works are deeply nostalgic, a memory of the deli counters and diners of his childhood that by the 1960s were being overtaken by supermarkets selling prepackaged food. A lonely slice of pie, or a melting ice cream, carries the anxiety of the American Dream on the turn, as a new era of violence and uncertainty took hold. To 18 January 2026, Courtauld Gallery, London.

2. Letizia Battaglia: Life, Love and Death in Sicily, Photographers’ Gallery

When I finally got to see this survey of the remarkable and terrifying career of Sicilian photographer Letizia Battaglia during its final week in February, I could barely think of anything else afterwards, and had no choice but to go back for a final look before it closed for good. Working almost exclusively in black and white, Battaglia slipped through gaps to get horribly close to the crime scenes she was sent to cover for daily newspaper L’Ora in the 1970s and 1980s. She made some of the most powerful and best known images of the Mafia’s bloody reign in Palermo, that though instrumental in the fight for justice, came at considerable personal cost.

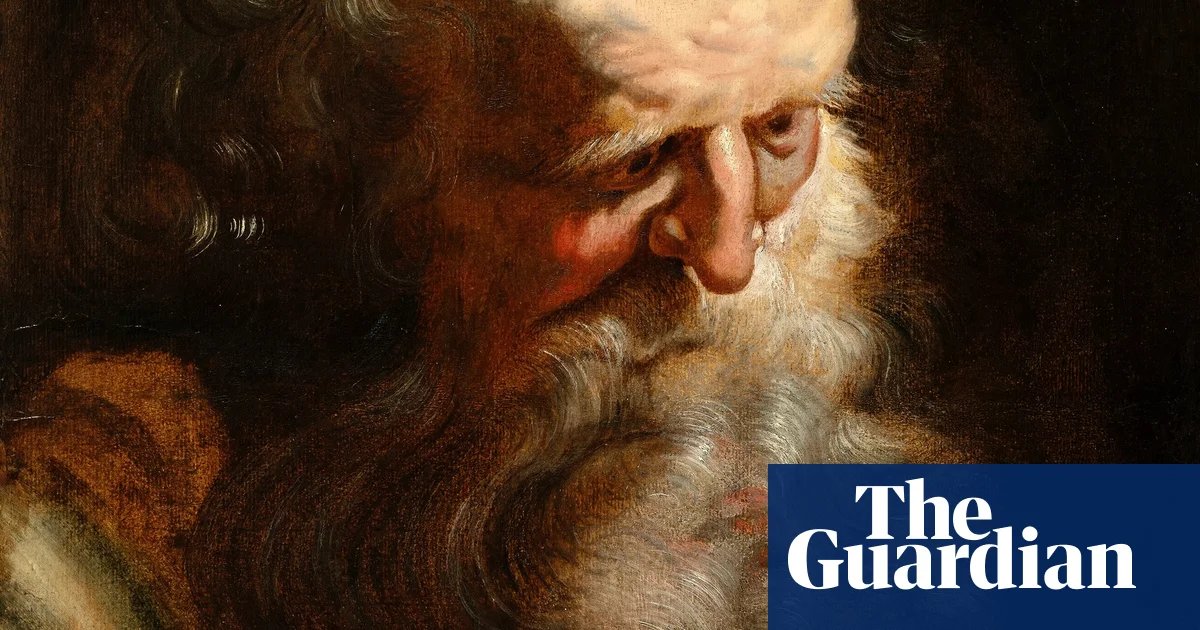

1. Munch Portraits, National Portrait Gallery

Small but perfectly formed, this show comprised a mere 45 paintings and prints, most of which had never before been seen in Britain. This was a chance to move beyond Munch the tortured soul, to see him instead as an inquisitive, culturally voracious member of society, operating a professional practice.

It was the perfect opportunity to study the Norwegian painter’s evolving portrait style, with which he captured the likenesses of Norwegian and European high society, from financiers and surgeons to the likes of Nietzsche, Mallarmé and Delius. He didn’t hold back in his judgements, either, and from psychedelic backgrounds to cartoon-style “action lines” he found countless perplexing and entertaining ways to say exactly what he thought.