Most artists aged 92 aren’t still producing works. Few are having exhibitions. And the majority certainly aren’t confident doing interviews via a computer screen.

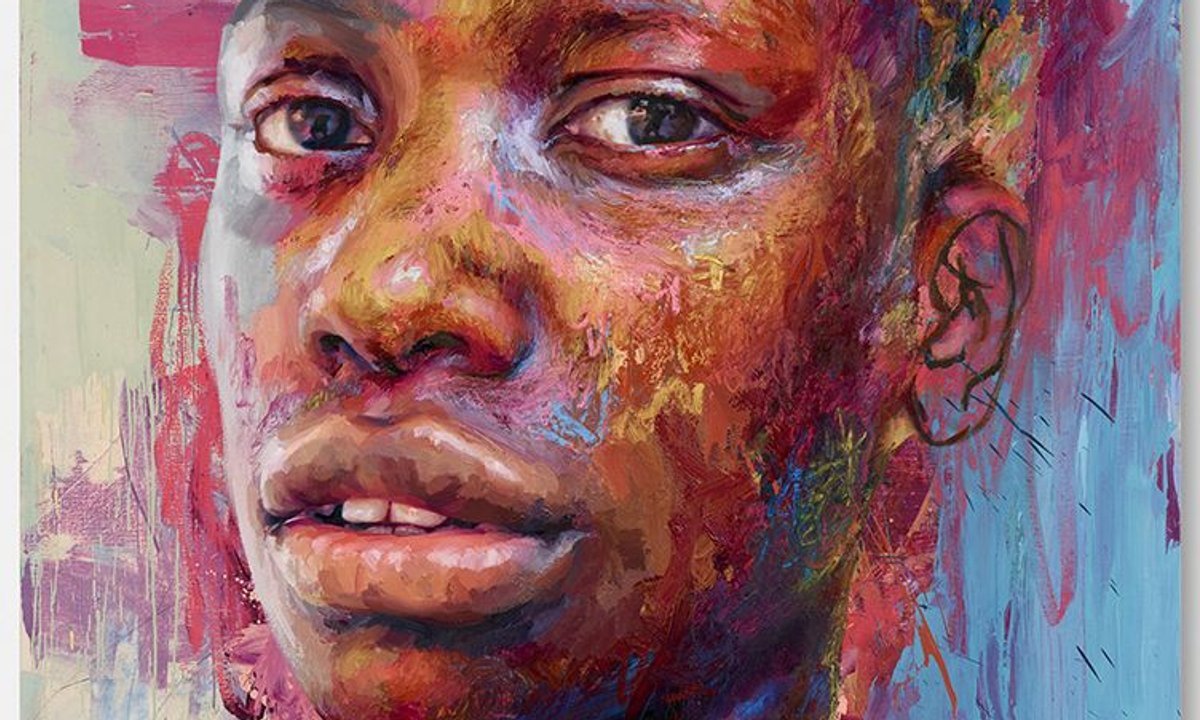

But Olga de Amaral isn’t like most nonagenarians. Talking to me on Zoom from her daughter’s office in Bogota, the Colombian seems as vibrant as the artworks she creates. With her white hair pulled back into a chic bun, her body draped in an elegant blue jacket, and her eyes glittering behind giant black round spectacles, she’s the Iris Apfel of the South American artworld.

Who she is — and what her art represents — she wants to make clear to me immediately. For a start, she says, she doesn’t really care what people think of her. And second, the reason she works is not to produce items for exhibitions or sales (including Sotheby’s, where this year she sold a work for almost $700,000). Creating pieces from various fibres — whether that’s linen and cotton or strands of horsehair, which she then knots, weaves, knits, sculpts and sometimes coats with gesso, paint or gold — is part of who she is. It’s what she has done since she was a child. If she doesn’t produce art during her waking hours, she doesn’t feel alive.

Cenit, 2019

©OLGA DE AMARAL. PHOTO ©JUAN DANIEL CARO

Círculo V-VI (diptique), 2004

©OLGA DE AMARAL. PHOTO ©JUAN DANIEL CARO COURTESY GALERIA LA COMETA, BOGOTA, COLOMBIE

Her true love — as her daughter, who is sitting beside her, attests — has always been textiles. That’s probably because, she surmises, they were always the most beautiful items in the markets she went to as a child. “I saw the way my mother would look at blankets and materials, the way she touched them. I could see that they were impressive. And I felt the love she felt.”

Wool was the first fibre she started to experiment with: weaving, knotting and shaping it into elemental forms. Then she tried horsehair “because there were many horses around”. At the start the shapes and patterns that she made were inspired by nature “because that’s all I knew: mountains, forests, plants, horses”. This changed when, after a degree in architecture, she enrolled at the Cranbrook Academy of Art in Michigan, the American equivalent of Germany’s Bauhaus school, and took lessons with Marianne Strengell, a Finnish-American experimenting with three-dimensional fibre art.

By the 1960s, de Amaral had been recognised alongside Sheila Hicks and Magdalena Abakanowicz as one of the world’s most innovative fibre artists, responsible for creating a new art form — modernist fibre art — that, for the first time, didn’t hang on a wall, but was often part architecture, part sculpture, part painting, part installation.

La Casa Amaral, Bogota

©JUAN DANIEL CARO

Bruma T, Bruma Q, Bruma R, 2014

©OLGA DE AMARAL, COURTESY LISSON GALLERY

Of the 90 works of hers on show at the Fondation Cartier in Paris, most are abstract and strongly graphic in their design: a “rainshower” of bright blue threads falling from the sky; a trio of upended gold-covered, rolled-carpet shapes; a Rothko-like almost Majorelle-blue layered hanging painted with a simple red square; a triangle of linen fibres hung in parallel rows, each painted in reds and blacks to give a 3D effect.

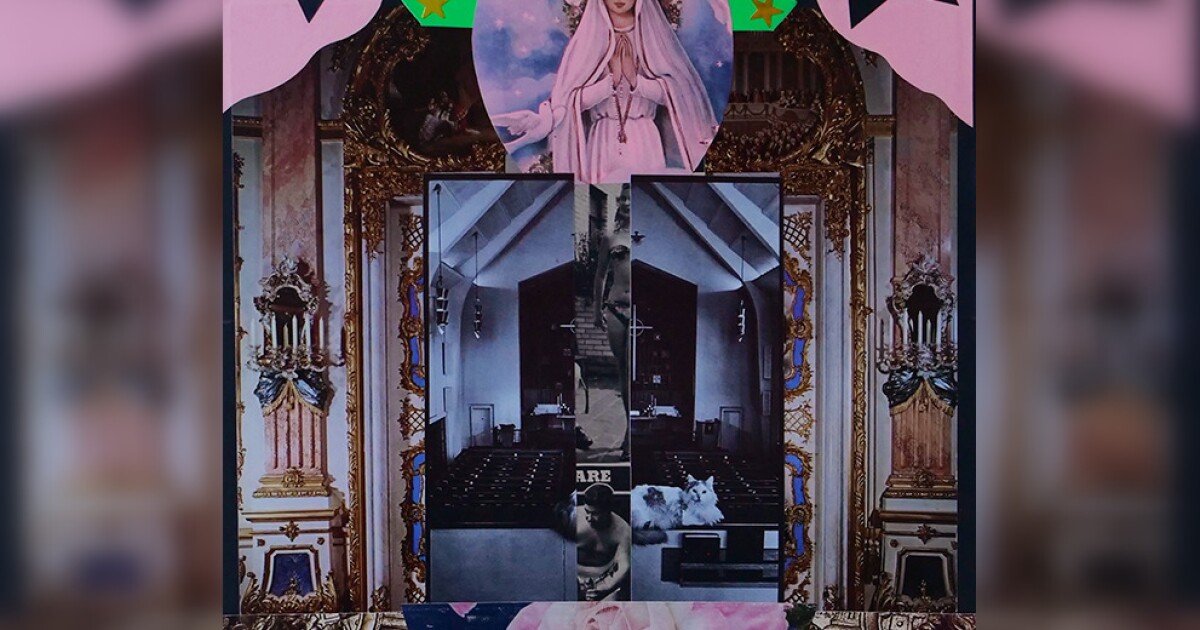

Perhaps the most famous are her “gold” works: intricate weavings into which she adds small squares of gold on gesso. Some are enormous, undulating hangings in vivid blue with little glints of gold, while others are pure-looking contemporary white “altars” of thread, stippled with gradations of gold.

A key part of her work is bright colour, particularly the hues of the Colombian countryside. “In the little towns in the campo, the walls of the houses were always painted white and blue. Everything was white and blue. I loved that. So at the beginning I used it a lot.”

Gold soon became her signature colour, however. “I can’t say why. I just fell in love with it,” she says. Perhaps it was its sheen and warmth, she says. Or perhaps its link with pre-Colombian art, or the local Catholic churches she’s visited all her life. “Also, in Bogata we also have a wonderful gold museum,” she adds. “Gold is everywhere.”

Bruma D1, 2018

©OLGA DE AMARAL, COURTESY LISSON GALLERY

Olga de Amaral in 2024

©JUAN DANIEL CARO

She first saw the metal being used in contemporary art by her friend the ceramicist Lucie Rie, who incorporated the Japanese technique of kintsugi — adorning cracks with gold powder — into her works. Soon after, de Amaral started to coat her enormous hangings, made of thousands of little woven squares, with gesso, then gold leaf. The whole process, she admits, “takes a long time. And I had to learn to do it and have special tools because gold is very delicate.”

Slowly her art started to appear in galleries round the world. After her work’s first European appearance in the 1960s in the third Biennale of Tapestry in Lausanne, leading institutions and collections began to follow, from the Tate Modern and Moma to the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris and the Art Institute of Chicago.

Why no European gallery has mounted a major retrospective of her work until now “is not clear”, she says, shrugging. “I don’t know why. And honestly it doesn’t bother me.” Although the work clearly does make her happy. “I love to do art, and that people will be able to see that is wonderful. I guess that it’s in Paris is fantastic — not because I need to be celebrated, but because I love my work. So the pleasure for me is that at last it, not me, is being recognised.”

Bruma T, 2014

©OLGA DE AMARAL, COURTESY LISSON GALLERY

Essentially, she says, making art is the love of her life, and all she wants is for other people to feel that love too. She loves making it, she loves doing it. And she is delighted that textile art has gone from “women’s work” and something “that’s not very manly to do” to an internationally recognised, non-gender-specific art form.

What does make her slightly sad it’s that she probably won’t get to see the greatest retrospective of her life’s work. The journey from Bogata to Paris is, she says regretfully, “a long and heavy one. While I have the energy to work — because works are my best friends — can I get on a plane? I’m not sure. We’ll see.”

The Olga de Amaral retrospective is at the Fondation Cartier pour l’Art Contemporain in Paris until March 2025, fondationcartier.com and is accompanied by a book of her works (€49)