Artist Olivia Erlanger has worlds inside of her. Or at least that’s what she told Contemporary Art Museum Houston curator Patricia Restrepo when asked a while back about what she would create if she could take on a big project with zero limitations—every artist’s dream. While there are plenty of people walking around with worlds inside of themselves, from folks with overzealous internal monologues to probiotic-poppers who take their gut health a bit too seriously, most of them don’t result in solo exhibitions.

Fortunately for us, Erlanger’s did. You can explore these inner worlds in Houston at her new show, If Today Were Tomorrow, which is open at the CAMH now through October 27. It’s the New York–based artist’s first solo museum exhibit in the United States, and one W magazine heralded earlier this year as one of the most anticipated shows of 2024. Through all newly commissioned work—from a short film to dioramas and sculptures—Erlanger transformed the museum’s basement into an exploration of what we call home.

Much of Erlanger’s work has been built upon the examination of “closed worlds,” or human-made and climate-controlled environments. These are worlds that should be quite familiar to Houstonians since the coupling of our city’s Herculean sprawl and oppressive climate means we spend much of our time hopping from one hermetically sealed environment to another: from home to car to work to car to bar to car and back home again. The exhibit continues that exploration while also taking inspiration from Erlanger’s research into the semiotics of suburbia.

“I’m really interested in the myth of the American Dream and how that relates to homeownership—that in the twentieth century, this idea that buying a home would result in some sort of social mobility. It’s kind of, in the twenty-first century now, you know, increasingly harder to achieve,” Erlanger said during a preview of the exhibition, before diving into the history of redlining practices and how it excluded vast swaths of Americans from homeownership, plus a bevy of other historic perils of property.

Erlanger’s pieces in If Today Were Tomorrow engage in that discourse while also exploring the ways the architecture of homes and the infrastructure of our built environment—from roads to appliances—create a “suburban noir” and all that leads to.

If you’re curious about what exactly suburban noir means to Erlanger, a Q&A her friend Aubrey Plaza did with the artist for Interview in the lead-up to the exhibit’s opening provides some insight.

“You love that shit,” Plaza said, when the discussion turned to suburban noir films like American Beauty and Safe and how they relate to the short film component of the show. “You love pill-popping suburban women just cutting themselves.”

“Suburban noir. Yes,” Erlanger replied. “It’s like a Gregory [Crewdsen] and Todd Haynes mashup, an ode to both of them.”

Make of that what you will.

The 17-minute short film Appliance is the first thing you see when you walk into CAMH’s basement, which has been separated into distinct zones designed to frame each other as you walk through the space. Upon descending the museum’s staircase, visitors enter a homey area, complete with a blanket-draped couch, a table and chairs, and other domestic accoutrements like a lamp and books. The furnishings are all made to look like the set of the film, and it’s on this furniture that guests can sit as they watch it. Written and directed by Erlanger, it tells the story of a protagonist named Sophie who moves into a new home only to be haunted by strange noises and visual distortions that all seem to be perpetrated by her appliances.

Or are they? A psychic and her small child come over to investigate.

Instead of personifying the appliances, which the artist says wouldn’t have been very chic, they’re all stationary. Though nonliving, they do play heavily into the film’s soundtrack by way of on-set recordings, which, in effect, give them a voice. It’s like if Ryan Murphy made an adaptation of The Brave Little Toaster where, instead of setting off on a magical adventure, the merry band of appliances all decided to stay home so they could poltergeist their owner into a 5150.

It will make you want to unplug your oven and yeet your Instant Pot into the ship channel.

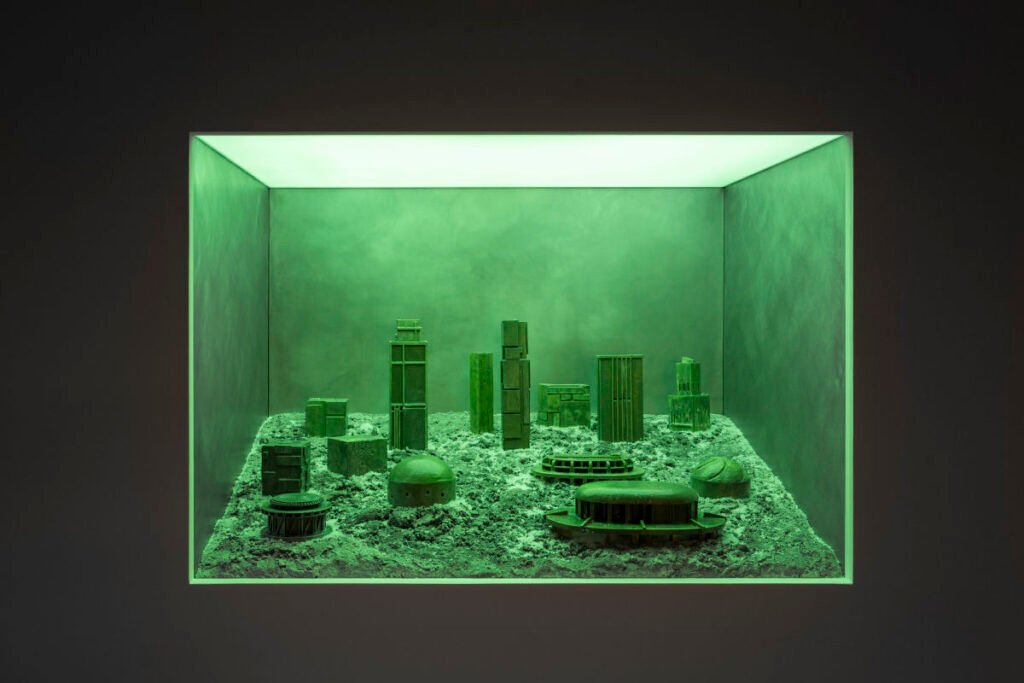

Erlanger’s exploration of property continues in the diorama section, located to the left of the film viewing area. The four dioramas each display distinct environments: a city, a park, a mountainscape, and a desert mesa. They’re meant to explore the ways in which we delineate property and ownership and the equity concerns that result from those delineations. The diorama of the park, for example, explores the economies of shade and how studies have shown that affluent areas tend to have more trees, leading to cooler temperatures.

Meanwhile, the cityscape, which sports a futuristic vibe and an ominous green atmosphere, features brutalist architecture and buildings that appear to be mostly vacant, which you could take as a nod to the speculative nature of real estate. The streets are also barren and free of any bike paths or pedestrian walkways, a backslide in livability that we imagine would leave Mayor John Whitmire salivating.

Behind the dioramas you’ll find Eros (when the night was last dark), a sculptural piece in which Erlanger has embedded polished aluminum arrows into the walls of the museum’s central staircase. The arrows form a partial star map of the sky over Houston on January 26, 1880, the day before Thomas Edison patented the light bulb, which, according to Erlanger is “the last day the sky was dark.” It was a time before light pollution obscured most of the stars by way of streetlights and, depending on where you live in Houston, chemical plant flares.

The decision to make the arrows out of aluminum was inspired by Ovid, who in Metamorphoses wrote that Eros had two arrows: a golden one that inspires desire and a leaden one that repels. According to the artist, the myth, as it relates to the sculpture, is meant to represent the conflicting desires to both return to and escape from the home.

The final section of the exhibition takes things to a planetary scale. Antimeridian and Prime meridian are two massive planet sculptures, one painted in blue and the other yellow, that present stylized representations of suburbs. On the globes, small homes, featuring windows filled with light, are connected by a crisscrossing of highways that circumnavigate each of them. According to Erlanger, they’re meant to reflect the ways in which urban epicenters are connected to the suburban periphery.

The featured highway is a representation of I-95, the main north-south highway used to navigate the East Coast, where Erlanger was raised. It was a smart choice for her to select that highway instead of, say, the sprawling Katy Freeway, as there wouldn’t have been room for any of the houses.

Like the other pieces in the exhibit, this one too is an exploration of the American myth of social mobility through home ownership. And although you can choose to navigate the separate spaces in whatever order you would like to, it makes sense to end your journey in this planetary portion of the show.

Carl Sagan has that famous excerpt from his book, Pale Blue Dot, which was inspired by the image Voyager 1 took of the Earth in which our planet appears as a tiny speck in a massive sea of space.

“Look again at that dot. That’s here. That’s home. That’s us,” Sagan wrote.

In a way, Antimeridian and Prime meridian are representations of what most of humanity actually sees the Earth as. Instead of a small blue dot magically lost in the cosmos, they view our planet as a massive piece of property to be gobbled up, delineated, and developed through, as Sagan wrote, “the folly of human conceits.”

And in Olivia Erlanger’s worlds, there are few things more foolish than a suburb.