I didn’t intend to fall in love with Erica Rutherford. In fact, before I saw the late Prince Edward Island artist’s survey exhibition at the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa, I had never even heard of her. One walk through Erica Rutherford: Her Lives and Works later, and I was in the back of a cab, hastily pitching a story to my editor.

Rutherford’s paintings had an immediate and profound effect on me, which only deepened after I discovered more details about her extraordinary biography. It’s a travesty that this important Canadian artist –– the first from P.E.I. to have a solo exhibition at the NGC –– is only now getting the national and international recognition she is due.

“I knew nothing of her story when I saw the work. I was really blown away,” says curator Josée Drouin-Brisebois, who organized the National Gallery’s presentation of Erica Rutherford: Her Lives and Works in collaboration with senior curator Pan Wendt of the Confederation Centre Art Gallery in Charlottetown.

Wendt has been working on the exhibition for more than a decade. “I grew up in Prince Edward Island, and she was just kind of around,” he says. After settling down in the small community of Pinette in 1985, Rutherford enjoyed a kind of hometown hero status on the Island. “She was very influential on younger artists in P.E.I.,” Wendt says.

Wendt introduced Rutherford’s work to Drouin-Brisebois, who is director of national engagement at the NGC, when she visited Charlottetown in 2023. “He very rightly asked the question, ‘What has the National Gallery done for P.E.I.?'” Drouin-Brisebois says. “That really piqued my interest.”

While the exhibition was in development, by happy coincidence, Rutherford’s work was exhibited in the Tate Britain exhibition Women in Revolt! Art and Activism in the UK 1970-1990, acquired by the National Portrait Gallery in London and selected for inclusion in the exhibition Foreigners Everywhere at the 60th Venice Biennale. The timing was just right for Canada to mount its own celebration of this long-overlooked artist.

Canada has good reason to claim Rutherford, though she didn’t call it home until later in her life. Born in Edinburgh in 1923, she spent five nomadic decades seeking a place to belong, jetting from London to Paris to Ibiza to Missouri to Johannesburg, with a handful of other stops along the way (as well as four marriages, three divorces and two daughters). Rutherford received gender-affirming surgery in 1976, and afterward, moved to Canada, where she began living as her authentic self.

Acknowledging and understanding Rutherford’s identity as a trans artist is vital to a full appreciation of her work — but it’s also not the only facet that merits attention. “Her autobiography is called The Nine Lives of Erica Rutherford, which is, of course, a reference to her love of cats,” Wendt says, “but also the fact that through personas, she turned herself into a kind of work, and slowly established who she really wanted to be. Artwork was a vehicle for her life story.”

During the Second World War, Rutherford began her career in theatre, working first as an actor and later as a stage, set and costume designer. Then she moved to apartheid-era South Africa to manage a banana farm, and produced African Jim (1949), the first feature film made with a Black cast and intended for a Black audience. Thanks to funding from the National Gallery of Canada, the film has been newly restored, and is now in the permanent collection, along with two paintings by Rutherford. African Jim is presented in full in the exhibition alongside scholarship that places it in context and discusses its historical significance.

After Rutherford’s stint in South Africa, she returned to the U.K., opened a women’s fashion boutique and started getting serious about painting, creating muted, semi-abstract paintings and collages. She moved to Ibiza with her wife, Gail, and had a daughter, Susana. By this point, she was a great fan of Carl Jung, and she borrowed some of his ideas to use as coded language when describing her own struggles with gender dysphoria..

“She made statements to the effect that her work was always working through her self-image, her sense of herself,” says Wendt. “Making art was an arena for her to deal with the ambiguity of her identity.” In 1968, the family moved to the American Midwest, and Rutherford began teaching at universities. Her artistic style hardened into something more bold and controlled.

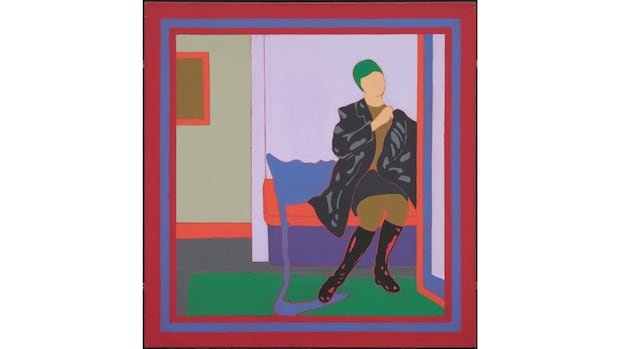

Her compositions from this time are claustrophobic, presenting faceless, stylized figures in saturated, discordant palettes. At the National Gallery, they are joined by photographic self-portraits Rutherford made as working notes for the paintings. Seeing all the paintings from this Women series grouped together in Ottawa changed Drouin-Brisebois’s reading of them. “I felt the amount of pain in the work,” she says.

In 1975, Rutherford came out to her friends and colleagues in Missouri, separated from Gail, and soon after felt the familiar restless urge to start fresh in a new location. She found acceptance in Prince Edward Island, where she had been visiting for many summers. She founded a beloved artist-run centre and printmakers’ guild and lived there –– eventually joined by Gail as a live-in companion –– until she died in 2008.

“Most of the audience in P.E.I. is not familiar with the Women paintings or the early work,” says Wendt. Locally, Rutherford was known “as this kind of grandmother figure,” he explains, “with her cats, flowers, beautiful landscapes and children’s illustrations. Gail describes it as her ‘exploring being a dainty female’ period.” The works from this era are still striking, with their Day-Glo hues and precise renderings, but the subject matter is far more demure, decorative and domestic.

In the late 1980s, Rutherford pulled out her old Olivetti typewriter and started composing her memoirs, which she published in 1993. Over the next 10 years, until dementia took her out of the studio, she produced the masterpiece of her long career: The Human Comedy. Delivered as the grand finale of the exhibition in Ottawa, this series of 50 large-scale oil paintings depicts mythical beings acting out scenes of gore and glory, like performers in an ancient play. “It brings everything together,” says Drouin-Brisebois. “It’s the theatre, figure painting, set design. It is about these strange beings that we are, these hybrids.”

“So much of our identities and social relationships are structured by stories and myth,” Wendt says. He believes that Rutherford must have recognized the importance of constructing her own mythic place as a way to find a peaceful resolution in her life. “If you put them all together,” he says of the works in The Human Comedy, “it’s like the fables that make up a culture or a world.”

Most importantly, the scenes in The Human Comedy make room for others. Where the alienated figures in Rutherford’s early works gasped for air, here they breathe easy. Technically, these paintings are looser and more gestural. The works show that the world is strange and full of horrors, but it’s also social and porous. “It’s as if she’s not alone in the world,” Wendt says. “I find them really uplifting paintings, even though they’re really disturbing.”

While Rutherford’s career survey is, expectedly, organized chronologically — guided by the structure of her own autobiography — it would be wrong to read her works as diary entries. As Wendt says, the idea of pinning Rutherford down “as one thing would be her worst nightmare.” “What she’s clearly interested in is open-endedness, and the idea that, in a certain sense, identity is actually a trap,” he says. While some criticize exhibitions that foreground the experience of marginalized groups for privileging advocacy over art, Rutherford’s exhibition demonstrates that the facts of a person’s life are not the end of their story.

“I think she’s a really interesting artist for this moment, because she complicates the question [of identity art],” says Wendt. “The work’s universal pull is obvious.” The exhibition is also a case study in how national institutions can improve. Rather than parachuting into faraway institutions without context, they can engage in thoughtful partnerships that honour local knowledge, family archives and decades of curatorial legwork.

While Rutherford is not here to enjoy the recognition she is receiving for her work, or her trans identity legitimized in most progressive nations, her art lives on as her legacy. Instead of being hidden away in secret or wielded as a cudgel, it is propping doors open, letting people in to discover a great multiplicity of meaning.

Erica Rutherford: Her Lives and Work is on view at the National Gallery of Canada until Oct. 13. The exhibition will then tour to The Rooms Provincial Art Gallery in St. John’s, Owens Art Gallery in Sackville, N.B., and MSVU Art Gallery in Halifax.