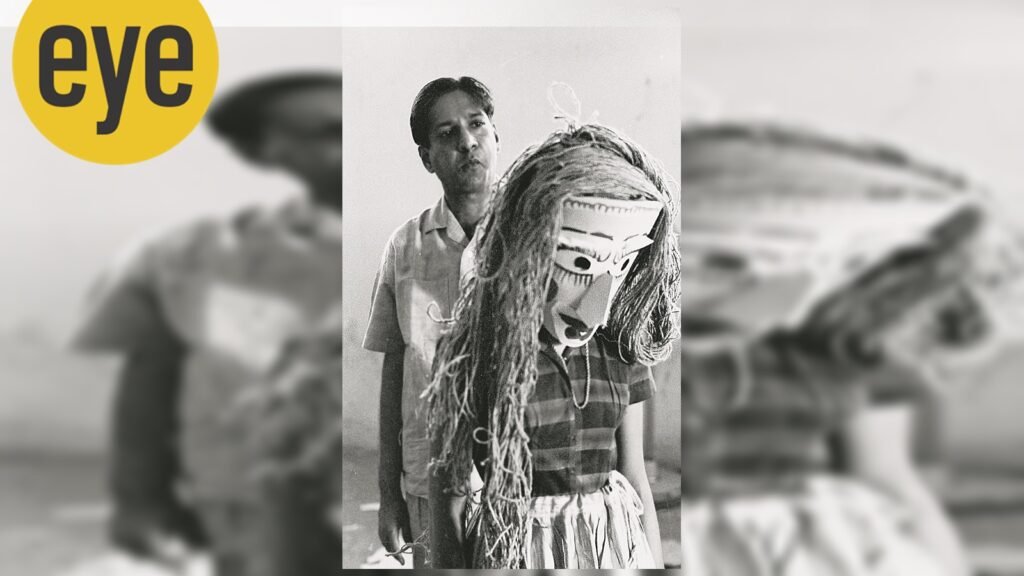

As a student in Santiniketan in the 1970s, artist KS Radhakrishnan recalls the excitement that preceded the arrival of KG Subramanyan at Kala Bhavana in 1977-78. Teaching painting at the Faculty of Fine Arts (FFA) at the Maharaja Sayajirao University (MSU) in Baroda at the time, Mani da — as he was fondly called — was in Santiniketan as a visiting fellow. “We had excellent teachers, including the likes of Sarbari Roy Chowdhury and Somnath Hore, and all of them spoke extremely highly of Mani da. As a student of sculpture, I spent a lot of time with him, learning how to approach my subject, the importance of values such as pluralism, compassion and connectedness. He would often sit under the Chinese Banyan tree on campus, light a cigarette and have long conversations over tea and coffee,” recalls Radhakrishnan, 68.

The Delhi-based sculptor was again visiting Santiniketan in the early ’90s, when he saw Mani da — then a resident of Santiniketan — standing on scaffoldings for long hours to paint his black-and-white murals on the facade of the Design department building. In 2009, when the colours started fading, Subramanyan returned to execute them again, mixing white ground and lampblack with Fevicol to paint images brimming with metaphors. It included peacocks perched on windows, prancing monkeys, tropical palms and mighty Durga. He was 85 at the time. “Age was no deterrent. He truly believed that everything had a life of its own. So instead of retaining the old, he chose to start anew,” says Radhakrishnan. In February-March, he curated an exhibition celebrating Subramanyan’s birth centenary this year at Arthshila in Santiniketan. An extension of the exhibition will travel to Delhi in winter. “Apart from his several contributions as an artist-scholar-poet-writer, his legacy includes the tremendous impact of his presence in MSU and Santiniketan. He was one of the most influential teachers of his generation,” adds Radhakrishnan. Subramanyan passed away in 2016.

****

The self-described “fabulist” and storyteller belonged to the last generation of artists who grew under the influence of the national movement. Subramanyan drew from diverse influences — mythology and folklore to calligraphy, Western Cubism and contemporary culture — to depict modern-day issues and narratives. While the numerous aspects of his creative genius included art, poetry, books and toy-making, he also imparted the values of artistic freedom to the illustrious students he mentored, which includes stalwarts such as Jyoti Bhatt, Haku Shah, Gulammohammed Sheikh and Mrinalini Mukherjee.

It would not be wrong to say that the polymath’s artistic trajectory was crafted by disposition and circumstance. While pursuing economics at Presidency College in Chennai, in 1943 he was jailed for six months for his participation in the Quit India Movement. His subsequent debarment from government colleges led his elder brother to approach Nandalal Bose for Subramanyan’s admission to Santiniketan. Tagore’s varsity introduced a new world to the young Kuthuparamba-born Tamil Brahmin from Kerala, who had grown up admiring temple murals and sculptures. Studying under the stalwarts of modernism in Bengal — Bose, Ramkinkar Baij and Benode Behari Mukherjee — he developed a language rooted in the indigenous traditions of India that also reflected global art practices. He would often recall how he was grateful to Mukherjee for allowing him to assist during the making of his monumental mural Life of the Medieval Saints at Hindi Bhavana in Santiniketan. His works in the early ’50s were also influenced by Baij’s expressionism.

Working as a freelance artist and vocational trainer at a rehabilitation centre for post-Partition refugees in Haryana in 1949, a clipping of a newspaper advertisement for vacancies at the newly-established FFA sent to him by artist-friend Sankho Chaudhuri took him to Baroda. In 1951, he became one of its youngest faculty members. The driving force behind the widely awaited Fine Arts Fair during its initial years in the ’60s, his toys were among its highlights. His students also recall his unconventional techniques — from teaching structural design by drawing on the floor with chalk, to appointing a craftsperson to teach a course in the department. The versatile and prolific modernist also involved students in his projects to introduce them to the varied techniques of mural-making.

Bhatt, his student at FFA, recalls assisting Subramanyan on his first independent mural for Jyoti Ltd in Gujarat in 1955. “My batchmate Feroz Katpitia and I worked with Mani da every evening, for almost a year. What we could learn during this, and three-four other mural projects, was manifold. It perhaps taught us more than the actual classroom curriculum… It also informed the visual language I followed for my own paintings and murals and is probably still alive in me,” says Bhatt, 90.

Recalling how the modest Padma Vibhushan awardee lived, Bhatt adds, “Mani da was very simple and always wore kurta-pajama and a sleeveless jacket. When we were working in Chinhat during Diwali vacations (1962), he had rented a small house in Lucknow for himself and his three student-assistants. Feroz was quite fond of good Western attire and also loved smoking cigarettes. Mani da had appointed a housekeeper to look after household activities, including cooking. Once he needed something from the market but the housekeeper was nowhere to be found. Eventually, when he returned and was asked where he had been, he replied, ‘I was sent to buy cigarettes by Bada Sahib.’ He had no idea who the real Bada Sahib was!”

****

After studying at London’s Slade School of Fine Art in 1955, through the ’60s and ’70s Subramanyan worked closely with craftspeople first as the deputy director of Weavers’ Service Centre in Bombay in 1958, followed by his appointment as design consultant for the All India Handloom Board in 1961, and president of Crafts Council of India in 1974. Like his other engagements, here too, he strove to build bridges between binaries. In a 1976 letter to the chairman of World Crafts Council, he wrote: “This role of the WCC is the more attractive one to me — to discover authentic pockets of craft practice all over the world, to study their structure, to document products and expertise, to bring together craftsmen from different parts of the world into a kind of fraternity, to help in the training of a new generation of craftsmen, to elucidate the necessity of craft practice in an industrialised society.”

While in 1963 he made a terracotta mural for the Ravindralaya building in Lucknow, based on Tagore’s play, King of the Dark Chamber, his art also reflected his engagement with the weavers, where he adapted their techniques into his own practice, producing powerful works such as the monumental textile relief showcased at the 1965 New York World Fair. Adapting old techniques of terracotta and glass paintings, he exemplified how older practices could be reinvented.

****

His first illustrated book for children — also cited among his initial politically explicit works — was conceived in the aftermath of the 1969 Gujarat riots. In When God First Made the Animals, He Made Them All Alike (1969), the disillusioned Gandhian spun a fable to emphasise how animals once lived as one single family. When they chose to divide themselves into species, they lost empathy and discovered violence. If in Robby (2008) he allowed readers the joy of embracing different identities, Our Friends, the Ogres (1985) was presented as a “parody of industrialisation and capitalism”. Rooted in the Emergency, The Tale of the Talking Face (1998) was an allegorical satire meant to question absolute power through the story of a princess whose autocratic rule brought suffering to her people. “He was not a political artist who was constantly dealing with political subjects, but his art reflected his deep engagement with what was happening across the world, and also how, perhaps, others were responding to it — which is also why he described himself as an artist-activist, not an activist-artist,” says art historian R Siva Kumar.

The following decades saw powerful politically-charged depictions, including famed terracotta reliefs such as Generals and Trophies (1971), made in response to the atrocities during the Bangladesh war of independence, and Anatomy Lesson (2008) that had dismembered body fragments representing collective turmoil. Paintings such as The City Is Not for Burning (1993) and Massacre of the Innocents (2002) were also born out of conflict situations. “The best incentive for civilised living can come only from loving the world. This alone will force everyone to live in peace, to care for the environment like it was a common park,” he stated in an interview with Siva Kumar (published in a catalogue for a 2014 exhibition in Kolkata, presented by Seagull Foundation for the Arts).

Cultural theorist and curator Nancy Adajania notes that Subramanyan’s political work also needs to be located within “his continuous process of political philosophising”. In the recently-concluded survey exhibition “One Hundred Years and Counting: Re-Scripting KG Subramanyan” at Emami Art in Kolkata, she pursued this objective, also contemplating his ambivalent take on female agency and sexuality in a critical spirit, through work beginning from 1953.

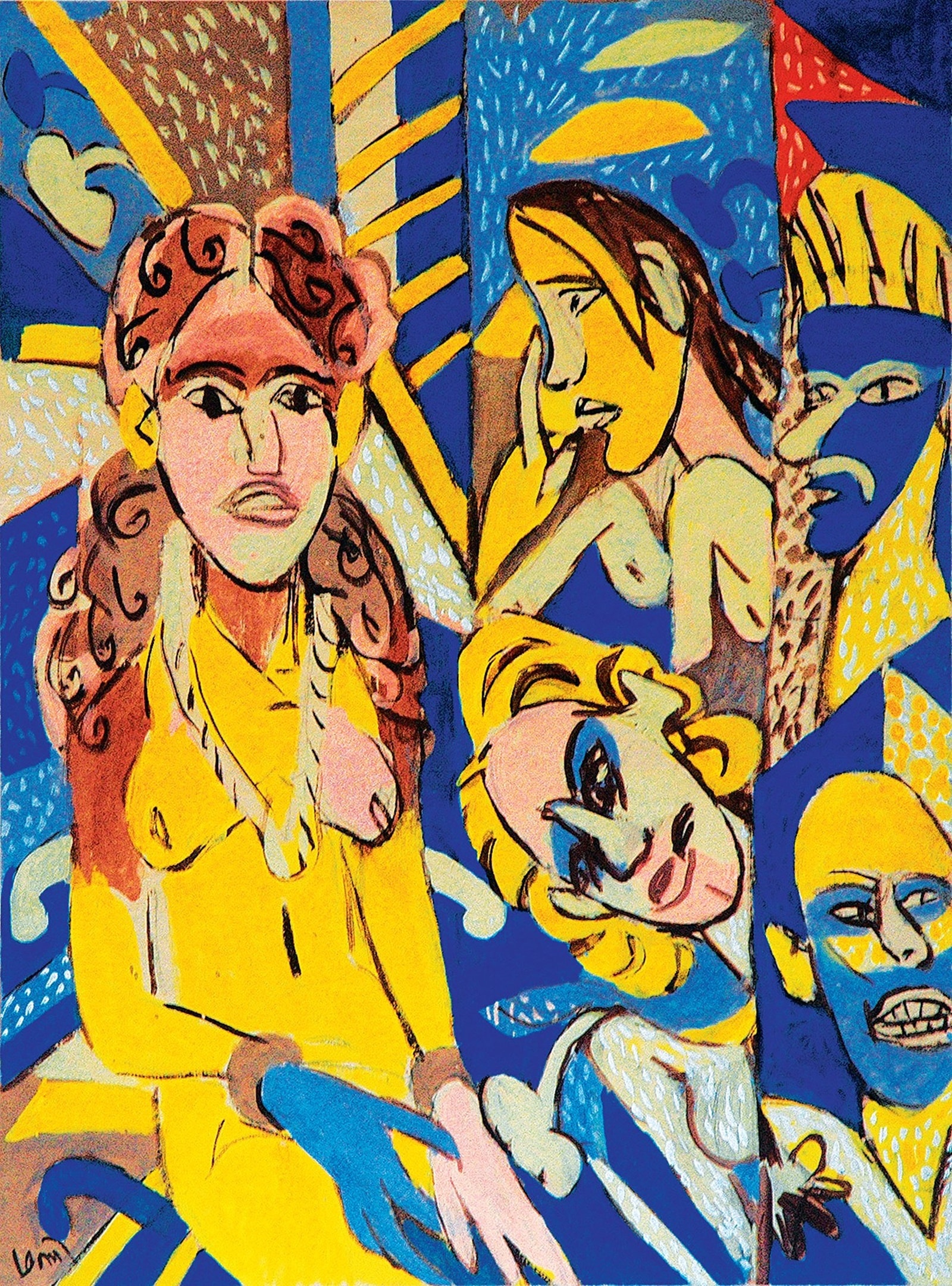

“He constructed and deconstructed the female figure in myriad ways, from the powerful bahurupee goddess-women hybrids, which occupied the liminal space between the sacred and the voluptuous, to the good mother/bad mother stereotype, as well as the tantalising women gazing unabashedly at the viewers. The female figure was often an object of sexual pleasure or a source of anxiety in his work,” says Adajania. She juxtaposed Subramanyan’s work with the practices of female artists Mrinalini Mukherjee and N Pushpamala “who were inspired by his non-hierarchical approach to art, yet reinterpreted female desire from a feminist perspective”.

There are personal memories, too. Artist Indrapramit Roy, associate professor at FFA, notes how the artist with a “dry humour” and “indomitable spirit” forever kept the doors of his home open. “As soon as one entered, they were offered tea and sweets. We sought his advice on so many occasions. Extremely generous, he never let anyone down, whether approached to contribute for an art fair or a charity event; he opened exhibitions of so many young artists,” says Roy. He shares how Subramanyan’s Saturday lectures at FFA in the ’70s weren’t limited to academic discourse, and drew students and teachers from across departments.

—————————————————————————————-

Story of an Artwork

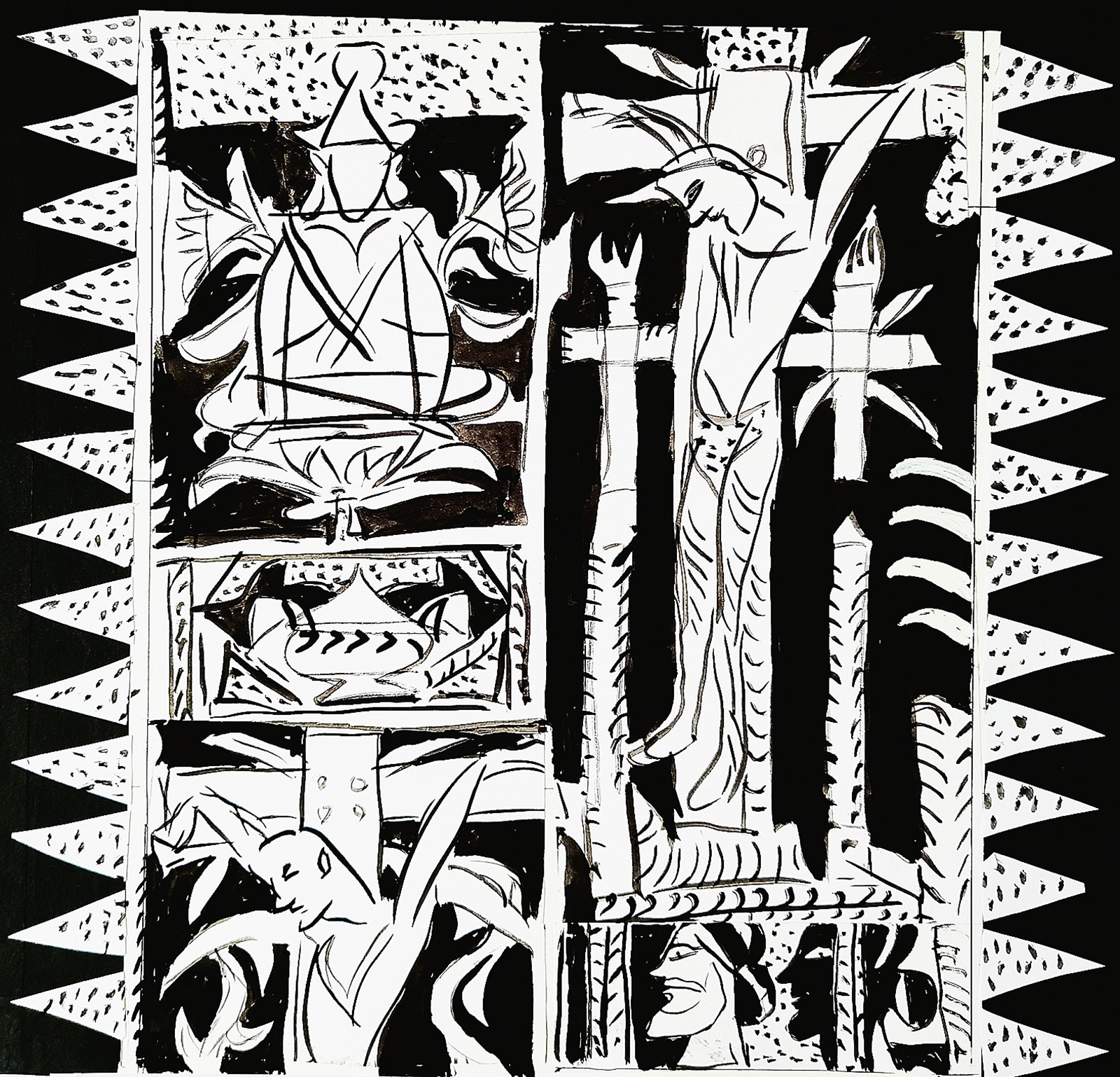

Art historian R Siva Kumar on War of the Relics, 2013

His last mural, painted barely three years before he passed away in 2016, was a comment on the most devastating conflict of the times, the war over relics from the past, especially religious. Although the communal tension unfolding around him was the immediate spur, he used it, as he often does, to contemplate the larger issue underlying the present reality. Rather than acting as a pacifist, in the mural, Subramanyan draws our attention to the absurdity of waging war over the relics of religions that were once devised to bring people together and foster fraternity. He found it disturbing that instead of moving forward and exploring possibilities of larger harmonious coexistence, we are reviving medieval mindsets and initiating new crusades and sectarian violence in the name of religious, national, racial and other identities.

On the one hand, by drawing upon religious motifs and heraldic images from different cultures and periods of history, he alluded to the present conflict’s history stretching back into the Middle Ages, and on the other, by rendering the mural with the boldness of graffiti, he gave it a sense of urgency. Its chaotic composition also hints at how human follies can potentially destroy social fabric. Completed after a hip replacement surgery, he worked on four-foot square canvases that came together to complete this 36×9 ft mural.