Keep out! That, seemingly, is the unfriendly message conveyed at the start of this centrepiece of the Edinburgh Art Festival, a stunning retrospective of ceaselessly inventive work by the 68-year-old British artist Andy Goldsworthy. Despite the public’s adoration, he still undervalued by the art establishment in this country.

An impenetrable screen of rusty barbed wire, like a rampant and malignant thorn bush, twisted around and between a pair of imposing columns, impedes progress into the galleries of Edinburgh’s Royal Scottish Academy. Don’t be deterred. Far from acting as a barrier, Fence (2025) – as this installation is called – elicits our engagement by confounding expectations.

Fence is an impenetrable screen of rusty barbed wire twisted around and between a pair of imposing columns – Stuart Armitt

It’s 50 years since Goldsworthy – the son of a mathematics professor who spent much of his teens working formatively as a farmhand – enrolled as an art student, not at one of London’s fashionable colleges, but in Lancashire, at Preston Poly. Ever since, this former motorcycle gang member, with a hazy tattoo of Elvis Presley on his forearm, has remained apart from the metropolitan art world. “I’m an outsider in every respect,” he told me defiantly this week. (The Tate owns next to nothing by him.) It probably didn’t help that, during the 1980s, Goldsworthy’s art was featured on Blue Peter.

Goldsworthy, a former motorcycle gang member, has remained apart from the metropolitan art world

Typically, his work takes one of two forms: large, site-specific installations in the great outdoors (involving, say, cairns and arches or surreal, switch-backing dry-stone walls), or ephemeral interventions also in natural settings that, before they disappear, are photographed for posterity. Examples of the latter, inside the exhibition, include photographs of a beach-ball-like clump of yellowing leaves, and a black-and-white zig-zag fashioned from the split feathers of a dead heron.

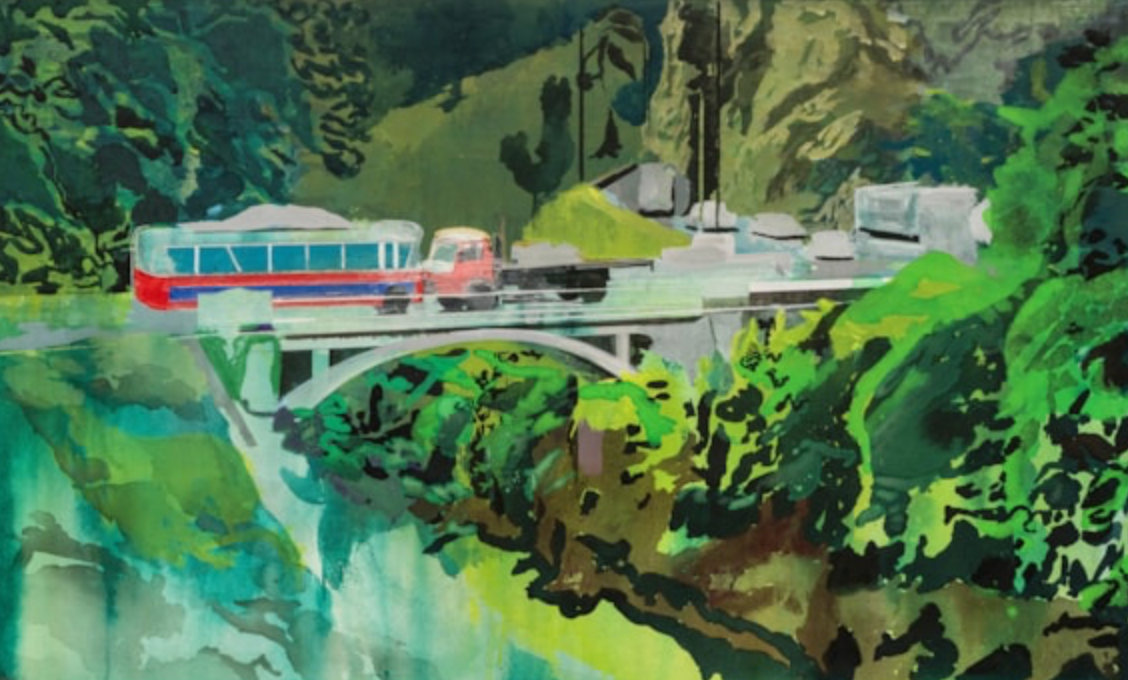

His art often takes the form of large, site-specific installations in the great outdoors, such as Frozen Patch of Snow – Andy Goldsworthy

The trouble is, these photographs are often too lyrical and pleasing to the eye for Goldsworthy’s own good, and there’s a perception that – compared with the supposedly tougher conceptual output of other British Land artists such as Hamish Fulton or Richard Long – his imagery is mindlessly bucolic.

This is unfair, as Fence – like the wider show – insists. Goldsworthy’s first big British exhibition since one at Yorkshire Sculpture Park almost two decades ago reveals him to be a prickly, obsessive artist capable of evoking difficulty as much as delicate beauty – as befits his vision of the land that, for decades, has inspired him.

Cracks and fissures abound in his work, which is also preoccupied with walls and fences, and confronts contentious rural issues, including land ownership and access. Unlike, say, Long, whose subject is the wilderness (and despite having worked at the North Pole), Goldsworthy is an artist of agricultural land and labour – who has also, surprisingly frequently for someone so associated with nature, made art in cities.

Cracks and fissures frequently appear in his work (Elm leaves held with water to fractured bough of fallen elm, October 2010)

He’s unafraid, too, to tackle lofty themes. In an early gallery, here, he presents Skylight (2025), an enfolding, chapel-like installation of cascading (or ascending?) interlocking bulrushes gathered from lochs, illuminated only by daylight from a grimy aperture above.

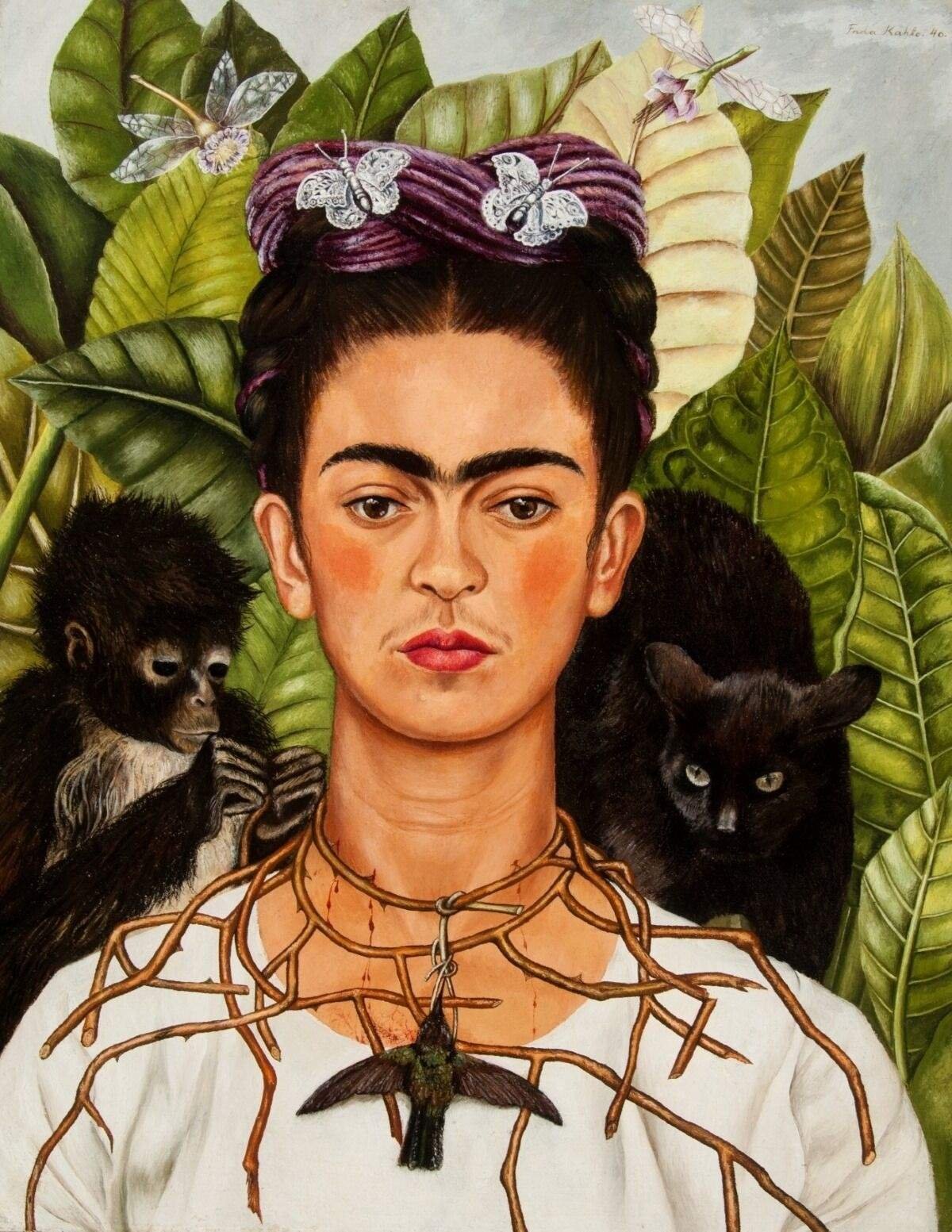

Nearby, he lays out a companion piece, Gravestones (2025), an expanse of lumpy stones of various sizes displaced, during burials, from more than a hundred graveyards in Dumfries and Galloway, where he’s lived since 1985. The former seems to levitate, and evoke the heavens and ethereal things; the latter, ponderous and apparently immovable, speaks of the inevitability of death, and – also naturally lit – should be especially gloomy come the show’s end, in November.

A proposal drawing for Gravestones, an expanse of lumpy stones of various sizes displaced during burials from graveyards – Andy Goldsworthy

“Of course, the land can be tranquil,” Goldsworthy says, while finishing an installation of battered work gloves pinned to a board within a stairwell recess. “But it’s also tough, difficult, challenging, brutal, and gory.” The same could be said, surprisingly, of his art, which is both beautiful and raw.

Runs from 26 July until 2 November; tickets: nationalgalleries.org