Artificial Intelligence may be a cause for concern across many industries, but a panel of artists at Miu Miu’s Tales & Tellers program during Art Basel Paris approached technological advances with moderate enthusiasm.

This year’s inaugural event, held on Oct. 16 and 17, brought together directors, talent and artists who participated in Miu Miu’s Women’s Tales and/or collaborated with the fashion brand. The third panel of the series highlighted discussions between dancer-choreographer Celia Rowlson-Hall, choreographer Geumhyung Jeong, filmmakers Lila Avilés and Hailey Gates, and contemporary artist Shuang Li, and moderator Cécile B. Evans.

When asked how technology affects the creative process, visual and performance artist Evans discussed the intersection between art and tech. “I think a lot of our works get mistaken for being about technology when it’s just a condition of the time that we exist in,” she said. “A fork is technology because we didn’t want to eat with our hands anymore. A pencil is technology because we didn’t want to write in our blood. My phone is technology because we encounter so many images and people and instances that we would never be able to hold in our minds. In that respect, it’s a great privilege.”

However, Evans said technology is also something to be questioned and occasionally critiqued: “The phone is not just an extension of my body. It was a thing made by a company that also has intentions that go against what my body wants.”

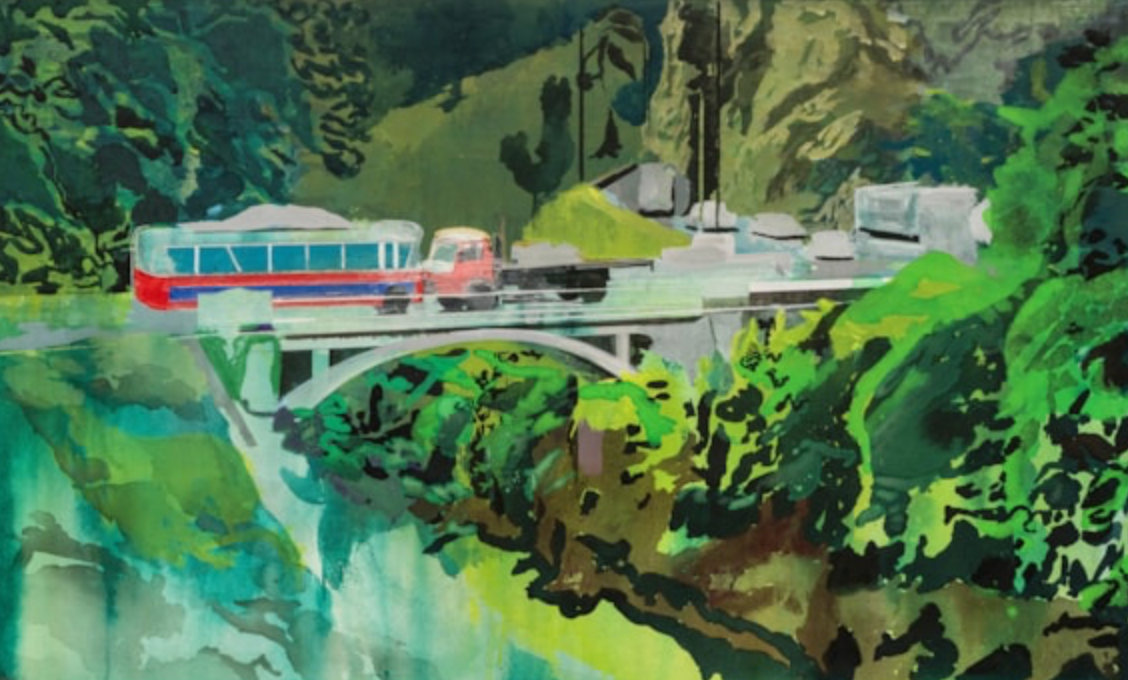

Rowlson-Hall shared that her next film project will feature AI along with classic film techniques. “I’m going to be using painted glass plates as a background that you film into, which is one of the oldest techniques used prior to CGI,” she said. “It’s just about implementing what is best for your vision and your artistry and take the good of what it is, but also honor what people were creatively figuring out as solutions in the past.”

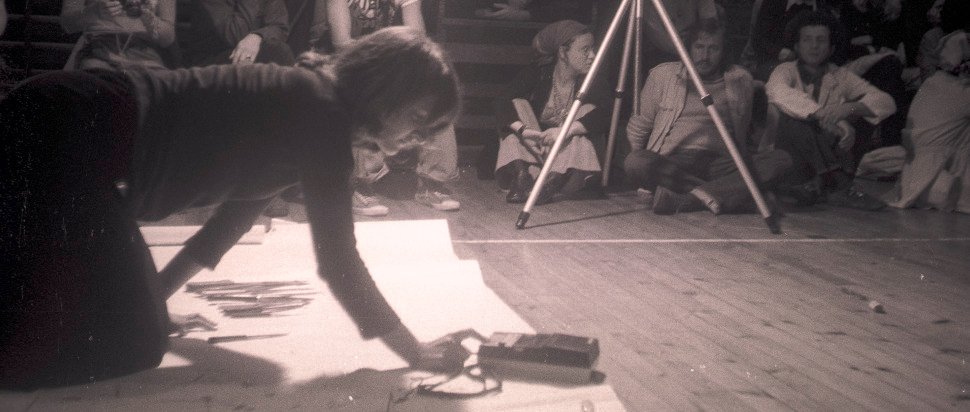

Choreographer and performance artist Jeong, who uses animatronic figures in her work, discussed the surprising effects of a recent project-gone-wrong. “There is a lot of failure throughout the process,” she said. “I don’t try to fail, but when a machine is doing something unsuccessfully, it becomes more human, and you’re creating emotion for the viewers, so in a way it’s more successful if I want to make a character.”

In general, the panel approached the future with a mix of optimism and, as Evans put it, “compassionate pessimism.”

“It’s basically to acknowledge that the systems and structures that we live in, many of them are broken and failing and that the world is very difficult, but people still have to wake up every single day and live in it,” said Evans. “There’s this great line of dialogue in Samuel Beckett’s Endgame that goes, ‘You are on earth, there’s no cure for that.’ And I want to propose that something like hope or similar, even if there is no cure, is a necessary form of compassion for everyone getting up and living in it.”

Aviles suggested that these complex circumstances are an opportunity to expand one’s artistic vision through curiosity. “Those moments that can be frightening are also seeds to ask more questions,” she said. “And to really try to engage with your art.”

Likewise, Rowlson-Hall insisted that a modicum of hope is necessary in her work. “If I do not infuse my work with some sense of hope, then I don’t think I am creating a future I want to live inside of,” she said. “I personally think it is my duty as a filmmaker and as a creator to create the world I want to live in, and that doesn’t mean creating something false around that.”

Meanwhile, Gates brought up the relationship between humor and tragedy in her work. “I was lucky enough to make one of the Women’s Tales, and I just want to thank Miu Miu for letting me make the film because I came to them and said, ‘I want to make a comedy about the military industrial complex,’ which they very generously let me proceed with,” she said. “But, for me, the importance of comedy in this truly, deeply horrific world that we live in is paramount because it’s really the way that we understand these horrors. So, as difficult as it is, I think I really lean towards laughing. It’s the only way to metabolize it I think.”

Piggybacking on Gates’ mention of the humorous side of tech, installation artist Li, whose work focuses on the gap between the digital lives we’re supposed to be living and the fragile infrastructure that supports that technology, shared her love/hate relationship with generative artificial intelligence chatbots. “When I write emails, I’m so dry, I’m just replying yes or no. And then, if I put it through [an AI chatbot with advanced natural language processing], they make me sound like a person,” she said. “That’s when I was so scared. I was like, literally, I sound more like a robot.”