“I’m one of those people that uses horror as catharsis,” said artist Robin F. Williams, as we walked through her current exhibition “Good Mourning” at P.P.O.W. in Tribeca. Vibrantly colorful gouaches with scenes inspired by horror films filled the central wall of the gallery, arranged like intimate film stills in a grid. Blood reds and ultramarine suffused their surfaces. Certain archetypes repeat: in some, women stand pensively, in darkened hallways, concern or confusion on their brows; others scream, blood-soaked and wild-eyed, at an unseen villain.

Robin F. Williams, 2024. Photo: Curtis Wallen.

This P.P.O.W. exhibition is something of a bookend to a pivotal professional year for the Brooklyn-based artist. Earlier this year, Williams, an Ohio native, opened “We’ve Been Expecting You” at the Columbus Museum of Art. The exhibition spanned over 17 years of her career and coincided with the publication of the first major monograph of her work. Brian Donnelly, better known as KAWS, loaned three works he owns by Williams for the exhibition. Demand for her work is strong; most recently, Alive with Pleasure sold for £88,200 ($115,339.35), reaching past its high estimate.

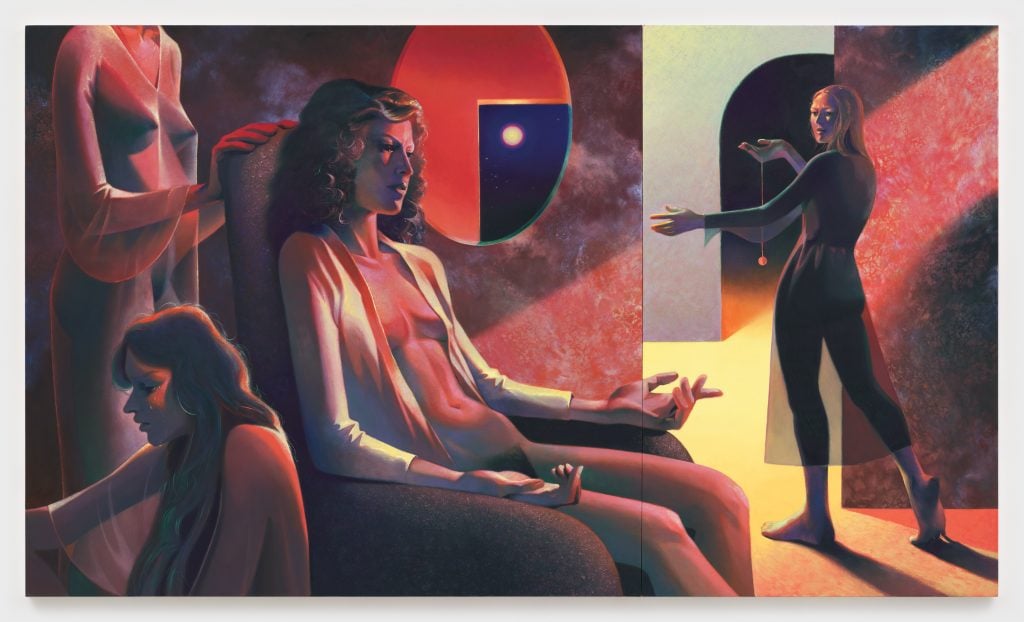

For her newest exhibition, she has taken inspiration from scenes in The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, Suspiria, and Carrie, among other films. “These are mostly from movies from the ’70s and ’80s, but sliding all over the highs and extreme lows of the genre,” she noted. These aren’t always 1:1 translations but imaginary scenes made from an “intuitive process of collecting images and processing the patterns.” In the gallery, the gouaches give way to large-scale paintings in iridescent pigments. Perception of these paintings shifts from step to step. These, too, take cues from horror while integrating (and interrogating) art historical and even sci-fi antecedents.

Robin F. Williams, Slumber Party Massacre 2 (2023). Courtesy of Robin F. Williams and P·P·O·W, New York. © Robin F. Williams. Photo: Ian Edquist.

The Theater of Cruelty

Williams is an avid cinephile who believes scary movies and the visceral responses they elicit offer a safe avenue for expressing complex emotions, for allowing uncertainty and contradiction. “Horror films give you a container for unsolvable, unspeakable, unexplainable.” she said, “Horror, comedies, romances, and porn all elicit unbidden bodily responses. We can experience wonder terror, and ecstasy, again and again.”

For Williams, movie theaters are “spaces where we can have a communal, ceremonial practice.” The darkened anonymity of theater is a place of collective escape into narratives. “We get together to have a physical release of emotion,” she said. “Maybe these moments used to be in a church, but America is such an evangelical Christian place that tries very hard to separate us from our body.”

The exhibition “Good Mourning” takes its name from a pulpy 1979 Gothic novel Flowers in the Attic, which was later adapted into a film. The ambiguity of the narrative appealed to Williams. “It’s a low-brow, sensationalist, young adult novel that was marketed to teens,” she explained. “But it has a very recognizable folk fairytale structure of evil villain witches and princesses and princes. It’s just a horrible story, where children are abused and, in the end, there is not a nice resolution or a lesson to be taken away. But there is an acknowledgment that cycles of abuse perpetuate themselves if no one breaks them.”

Artemisia Gentileschi, Judith and Maidservant with Head of Holofernes (c. 1623–1625).

Women appear, throughout these images, in moments of terror, realization, and transformation. In some ways, these works are a continuation of William’s ongoing investigations of folklore, gender, and the ways our online lives shape our perception. But they also more directly grapple with the messy realities of victimhood and trauma. “I think these paintings are about grief,” said Williams.

Tricks of Light

The artist said that the P.P.O.W. exhibition feels like a moment of transition. The exhibition (which closes on Saturday, October 26) offers a powerful vision of what contemporary figurative painting can explore.

The artist, for the first time, is working with iridescent pigments and an otherworldly glow characterizes the large-scale canvas works. Her choice of medium was partially inspired by the total solar eclipse earlier this year. The artist was in her native Columbus, Ohio, for the opening of the Columbus Art Museum exhibition, when the eclipse occurred. The city fell in the path of totality. Williams’s experience of the eclipse was an odd sensation of the contrast being dimmed. “It was a completely unfamiliar light source, a very strange way to be illuminated,” she said. “And there’s ominous, even dreadful sensations, that go along with it.” All that goes into these works, too.

Robin F. Williams, The Cult (2024). Courtesy of Robin F. Williams and P·P·O·W, New York © Robin F. Williams Photo: JSP Art Photography.

This uncanny light is also influenced by more mundane sources. Williams has long investigated the ways our online lives and technologies shape our realities (in a previous body of work, she imagined Siri, the disembodied ‘digital assistant’ on iPhones, as her central character). The paintings bear the heightened hues of digital glow and documentation. “There is a deep sensory color saturation in the horror films of the ’70s, ’80s, and ’90s,” she said, “But I’m also mostly not in a movie theater, I’m looking at a screen. That heightens and distorts how we perceive this imagery.”

Robin F. Williams, Out the Window (2023). Courtesy of Robin F. Williams and P·P·O·W, New York © Robin F. Williams Photo: JSP Art Photography.

Art History Horror Show

References to Baroque artwork, with its dramatic tenebrism, and even violent subject matter, surface again and again. The gouache, Slumber Party Massacre 2, shows a group of teenage girls gathered in the dark with candles dramatically lighting their faces, conjuring Artemesia Gentileschi’s Judith with her Maidservants as well as Georges de La Tour’s Penitent Madgalene, complex biblical heroines.

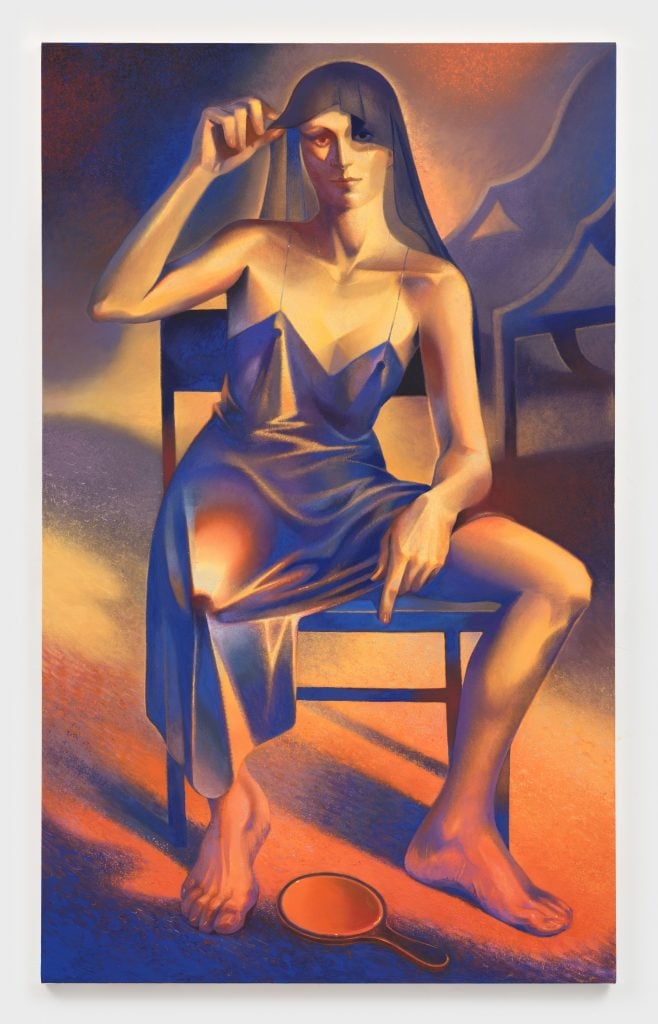

Robin F. Williams, Good Mourning (2024). Courtesy of Robin F. Williams and P·P·O·W, New York © Robin F. Williams Photo: JSP Art Photography

In Suspiria 1 , a woman appears with her mouth open and head thrown back, in violent terror. Compositionally similar, is another gouache based on the famous scene in When Harry Met Sally, in which Meg Ryan’s character fakes an orgasm. Both compositions are similar to Bernini’s famed Ecstasy of St. Teresa, with the nun’s almost pained expression of pleasure.

Williams’s works thrive in this prickly emotional terrain. In the show’s titular work Good Mourning (2024), a woman in a slip dress and a black veil, sits astride a chair. Her feet are bare, almost sculptural. She points down to a mirror on the ground in front of her. The painting reimagines Francisco Goya’s Black Duchess, a famed portrait of the recently widowed Duchess of Alba, adorned in a black veil. Goya and the Duchess were lovers, and, in his image, she points to the artist’s name which is written on the ground, committing herself to him.

Francisco Goya Year, Portrait of the Duchess of Alba (1797). Collection of the Hispanic Society of America.

Williams’s widow is sexually awakened even in grief, and melds the Goya work with references from a famed Anjelica Houston photoshoot and the infamous white dress Anna Nicole Smith wore to her husband’s funeral. “Sad and so sexy aren’t things we’re comfortable putting together,” said Williams “These are hybrid emotions, hybrid characters, people that don’t fit clearly into one category.” This complexity, Williams notes, in horror films, often takes the form of “gender slippage” where the protagonists are often unconventional women.

And while Williams’s works often linger in uneasy spaces, sometimes their conclusions are more open-ended than others. In Out the Window, Williams invokes Minimalist artist Carl Andre’s infamous words, “She went out the window,” in his 911 call following the suspicious death of his wife, Ana Mendieta. A dark-haired woman stands a the ledge of a window, two wine glasses beside her, one spilled, almost ominously. While Williams’s paintings often seem to offer alternate endings, at times, we are paused on a precipice where history’s circle seems set to spin around again.