Russia’s war in Ukraine continues to influence Alyona Yaseneva’s and her children’s art, although less so today.

Alyona Yaseneva is 39 years old, a mother of three sons and a painter. She is also the daughter of the renowned Ukrainian painter Oleg Yasenev, and the wife of Valery Stratyuk, 53, also a painter.

Today they all live and work in Rimavská Sobota, a town of 22,000 in southern Slovakia. Alyona and her husband arrived three weeks after the outbreak of the war in February 2022. Her father arrived later. This spring, in the town gallery, they presented their paintings alongside other Ukrainian artists.

Alyona exhibited, among other artworks, a painting of 528 crosses. The large black-and-white work evoked a great response. It shocked, but most importantly, faithfully depicted the pain the artist poured into it. Each cross symbolised one child killed in the war in Ukraine.

“Today there are even more of those children,” says Alyona.

Invitation from strangers

“We considered both Poland and Slovakia, a country close to Ukraine. We asked friends and acquaintances about who would be able to help,” Alyona says, describing the days before they fled Ukraine.

Through a few friends, they were informed that there was a family in Slovakia ready to take them in. The invitation came from complete strangers. Alyona did not want to believe it, surprised that someone wanted them all – an entire big family of seven.

“We said there were a lot of us, we also had a cat and rabbit,” she recalls. The answer was, “We have two dogs so feel free to come.”

“Don’t die without me!”

The days before they left were not safe at all. Alyona’s husband stated in a documentary how shocked everyone was by the war. The house they lived in was not built for shelling. They did not even have a cellar where they could hide.

The family lived 25 kilometres from Kyiv, under occupation from the first days of the war, the bombing close. There were days without electricity and since they had no gas, they could not even cook.

“We were hiding under mattresses. We don’t know if that would have really helped. But it helped then, at least mentally.

One time we ran to our hiding place. Our older son was the last one to run to us from the top floor, and he said, ‘Don’t die without me!'” the husband describes in the film with pain in his voice.

Alyona with her son Ivan. (Source: Elizaveta Blahodarova)

Alyona with her son Ivan. (Source: Elizaveta Blahodarova)On the road with pets

Today, Alyona sits with her eldest son Ivan in the community centre of the Kŕdeľ civic association on the Main Square in Rimavská Sobota and describes how they fearfully got into cars in March 2022. The parents and their three children – Ivan, who is now 16, Zachar (10), and Anton (8), Alyona’s mother, also a painter, and her husband. And of course, they were taking the cat and the rabbit.

They arrived in Rimavská Sobota in the evening, at the exact address, where a cooked meal awaited them.

“Of course, we were stressed. We were welcomed by very nice people. It all seemed unreal to me that something like this was happening,” says Alyona. She adds that the family was attentive and kind, while they were lost and tired.

Having someone waiting for them and supporting them brought them peace.

“They told us right away that their house was our house, and we would live as a family, and that’s exactly what happened. After two years, they are like parents to us,” she describes her relationship with her hosts.

They not only helped the Ukrainian family with the first accommodation, but also with moving into a separate flat, the necessary paperwork upon arrival, arranging medical care and school for the boys.

A flock of refugees

The Ukrainian community in Rimavská Sobota and its surroundings consists of around 200 refugees today. The most active of them, Aleksander Zhukov, founded a civic association here. It is called Kŕdeľ (Flock), a community platform for Ukrainian refugees and local residents.

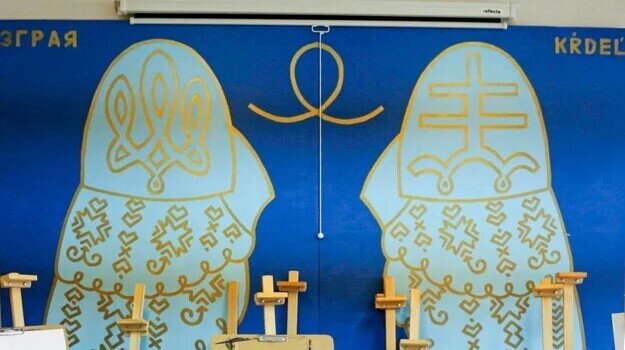

The association’s symbol consists of wings, one bearing the Slovak and the other the Ukrainian legacy. The flock for the refugees in Rimavská Sobota symbolises a group that can do something good together.

“Aleksander encouraged us to go and do something together, to help Ukrainians here and in Ukraine. He brought us together,” says Alyona, who herself thought about how she could help after arriving in Slovakia.

In Ukraine, she taught painting. She had her own private studio where she mainly taught children. Her husband painted pictures and already had his own clients. Alyona brought her passion for the teaching of drawing to Slovakia. She not only volunteers at Kŕdeľ, but also teaches academic drawing classes for children and adults.

To this day, she still teaches some of her Ukrainian students online. However, plans to expand the studio to Kyiv were interrupted by the war. The place where she used to teach already served as a military headquarters, and today it is a classroom.

Alyona has been devoted to art all her life. She graduated from an art school in Dnipro, her hometown in eastern Ukraine. Then, she studied painting at the National Academy of Fine Arts and Architecture in Kyiv, where her father Oleg is still a professor. Although he does not live in Kyiv right now, he commutes there from Rimavská Sobota for occasional consultations. He still has his students, holding consultations with them online.

Kŕdeľ logo. (Source: Elizaveta Blahodarova)

Kŕdeľ logo. (Source: Elizaveta Blahodarova)Drawing therapy

“I don’t like to draw what my mother tells me in class, I want to express my opinion and emotions in my paintings. When I have an idea in my head, I want to add my imagination and put it out there,” Ivan describes how he creates.

He says that drawing helps him.

“I can leave an emotion on the paper and when a year or two passes, and maybe I’m not in Slovakia any more, I’ll take it, look at it, and I’ll be able to relive those emotions and remember what was happening that day I drew it,” he says.

Alyona shows pictures painted by her boys. Cheerful rabbits and pandas were drawn according to the assignment. And then, there are many scenes from the war. The boys draw it often, though less and less as time goes on.

“A year ago it was much more. We have the paintings somewhere. I was thinking that we could also use them for an exhibition, a children’s exhibition – how children see the war, or even a joint exhibition, adults with children,” she explains.

Children often drew their house, with planes, missiles, Russian troops, and even the Russian president around it, she adds.

Ukrainian community worker has helped others. Now she needs help Read more

More black and red in Alyona’s images

The war also determined the atmosphere of Alyona’s paintings. A sad one, of course.

“My first paintings in Slovakia depicted our family stories, what it was like in our house, the journey from home to another country, what we felt, I wanted to portray all that,” she describes.

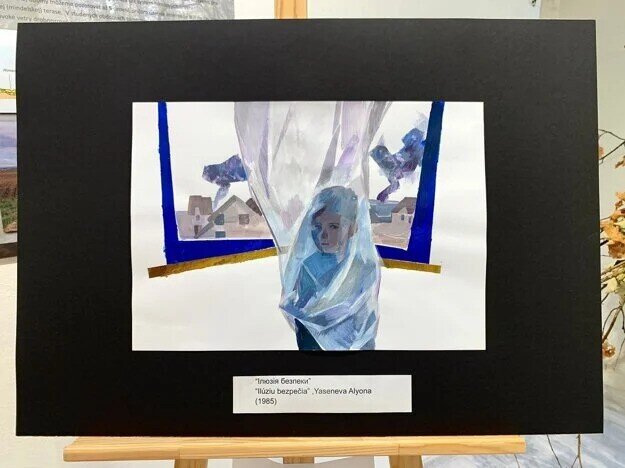

The titles of the first paintings she painted in Slovakia speak for themselves – Illusion of Safety or Journey to Nowhere. Alyona often drew her children, depicting how they experienced the war, standing by the window during the bombings.

“I was drawing the reality of what was happening,” she says.

Her paintings also reflected the war in terms of colour, applying more black, dark shades, and red, different to her previous work.

Although Alyona perceives Slovak nature as beautiful, when she paints it, the emotion of war prevails. And once again, black or dark colours will take their turn.

The opposite is true for her father, who came to Slovakia in the summer of 2023.

“After the outbreak of the war, my father couldn’t work for a long time, he didn’t have the strength. He only started to create here,” says Alyona. “While my works are sadder, my father’s are the opposite. What he used to create was black and white, grey. Now he creates more colourful paintings. He paints nature a lot,” she adds.

“Illusion of Safety”, Alyona’s first painting after her arrival in Slovakia. (Source: Courtesy of A. Y.)

“Illusion of Safety”, Alyona’s first painting after her arrival in Slovakia. (Source: Courtesy of A. Y.)It took some time to find friends

“The first day at school I understood almost nothing, I couldn’t speak like I do now, I just observed everything intensely. I made my first friends in the classroom – I had real friends by about the third month of going to school,” Ivan describes the beginnings in his new reality.

Before he began to go to school in Slovakia, he had no Slovak friends. He only met Ukrainian children in Rimavská Sobota.

He found two close friends. As a trio, they went out after school, travelled home together and talked a lot. When they could not understand each other, they translated words into English.

“I think my brothers feel a hundred times better than I do in the Slovak school,” he says. He is referring in particular to Anton, the youngest, who started first grade in Slovakia. “It’s all easy for him. After six months, he was talking very well and doing his homework as if he were a Slovak pupil,” says the eldest brother.

For him, Slovak was the hardest. For example, there are no accents in the Ukrainian language. However, Ivan is already handling all the other subjects well. He says that while children here have six lessons, in Ukraine they were at school longer, having up to eight lessons. He also finds the curriculum in Slovakia simpler.

Reading a spelling book

Alyona says with a smile on her face that if she had gone to school herself, she would know Slovak much better. She remembers how good it was for her when she read a spelling book with Anton, because she was learning with him.

“Even now, when I don’t understand or don’t know something, I ask Anton. Anton, how is it in Slovak? He already knows everything,” she adds.

Ivan joins in.

“Even after this conversation, I will tell my mum what she didn’t say right. I think about it all the time, you can’t say this and this like that,” he says kindly.

Alyona laughs out loud.

Ivan is a good student. He says that his grades are sometimes better than those of his Slovak pupils, even in Slovak.

“Yesterday we took a Slovak language typology test, I got a B and my friends got Cs,” he says.

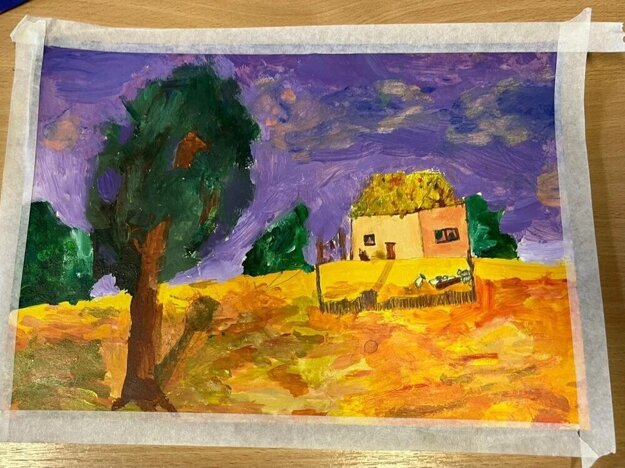

A typical Ukrainian village, according to Ivan. (Source: Katarína Kozinková)

A typical Ukrainian village, according to Ivan. (Source: Katarína Kozinková)Ukraine is s**t, said a pupil

A pupil at school told Ivan that Ukraine is s**t.

“I told him I didn’t want to have a conflict with him. I told him what I had been through in the war and how hard it was. Eventually he agreed with me, and we shook hands,” Ivan describes how calm and almost adult he was.

He has no such experience in his classroom at all, and he also feels support from his teachers. They do not make a difference between who is Slovak and who is Ukrainian.

If there happens to be a pupil at school who says that they wish Russia would win, according to Ivan it is something the pupil picked up from home and does not really understand what they are saying. And nowadays, he says, it often happens that many Slovak pupils even stand up for children from Ukraine.

He also experienced such support at the very beginning.

“They tried not to hurt me. They saw that I’d come from the war and how tired I was of it. That help meant a lot to me then,” he recalls of the good experience.

Alyona adds that it is unpleasant to meet people who do not understand how Ukrainians feel and what they have been through. However, in her opinion, this is happening less and less and as a family they have experienced a lot of humanity in Slovakia.

“Overall, I was surprised by the support,” she concludes.

On Telegram, she helps Ukrainians. In Bratislava, she stands with protesting Slovaks Read more

Fewer questions about the war

Ivan says that the first months of the war somewhat strained the relationships between the brothers.

“We didn’t have the strength for discussions, nor the patience, we were more closed off,” he recalls.

In Slovakia, the boys share a room. In the evenings before bedtime, they now talk about how their day was, what they experienced at school, and they only talk about the war and Ukraine when they have news that something happened back home.

“You have to live for today, I understood that. I can’t always think about the bad things. Soon I’ll be going to secondary school, and who knows if I’ll ever return to Ukraine,” says Ivan.

For a long time, they kept asking when we would return to Ukraine, says Alyona about the boys. Now, she says, they ask this question less, and sometimes even say that maybe they will not go back.

“They already understand that we don’t know what will happen. Maybe the war will last a long time. Nobody knows,” she concludes.

This text was produced with support from UNESCO under the Support for Ukrainian Refugees through Media programme, funded by the Japanese government.