The first picture you encounter was painted during a family holiday in Cornwall and dates back to 1900, the year before Bell became a student at the Royal Academy. Two thatched cottages cling to a steep slope by the sea. Punctuated only by the brown slits of windows and doors, their walls form a solid slab of white against the blue of sky and ocean. With its flattened space and limited colour range, the view is simplified almost to the point of abstraction.

It’s in striking contrast to the picture hung next to it, a Rembrandt-inspired portrait of her elderly father, Sir Leslie Stephen painted while she was a student. These early pictures indicate the twin poles of abstraction and figuration to which she was continually drawn, sometimes leaning towards one, sometimes the other.

It’s in striking contrast to the picture hung next to it, a Rembrandt-inspired portrait of her elderly father, Sir Leslie Stephen painted while she was a student. These early pictures indicate the twin poles of abstraction and figuration to which she was continually drawn, sometimes leaning towards one, sometimes the other.

Abstract Painting 1914 (pictured right) is one of her few totally abstract canvases and it makes you long for more. Floating on an ochre ground are six blocks of colour perfectly poised between stillness and implied motion. Separating the shapes are infinitesimally small gaps in the paintwork. And in one of her loveliest pictures, Still Life with Wildflowers 1915 (pictured below left) this idea is expanded to the point where each element of the composition is surrounded by a ghostly outline of raw canvas.

Yellow ochre was clearly one of Bell’s favourite colours. Later she added (Test for Chrome Yellow) to the title of Abstract Painting. The year before, critic Holbrook Jackson had described chrome yellow as “the colour of the hour… associated with all that was bizarre and queer in art and life, with all that was outrageously modern.”

The colour features in Bell’s calmest and most nearly abstract compositions. For instance, the wall behind her delightful portrait of pianist Saxon Sydney Turner is a soft ochre, while the fields curving round the pond at Charleston (pictured bottom left), the farmhouse she rented from 1916 until the end of her life, are portrayed in various shades of ochre and green.

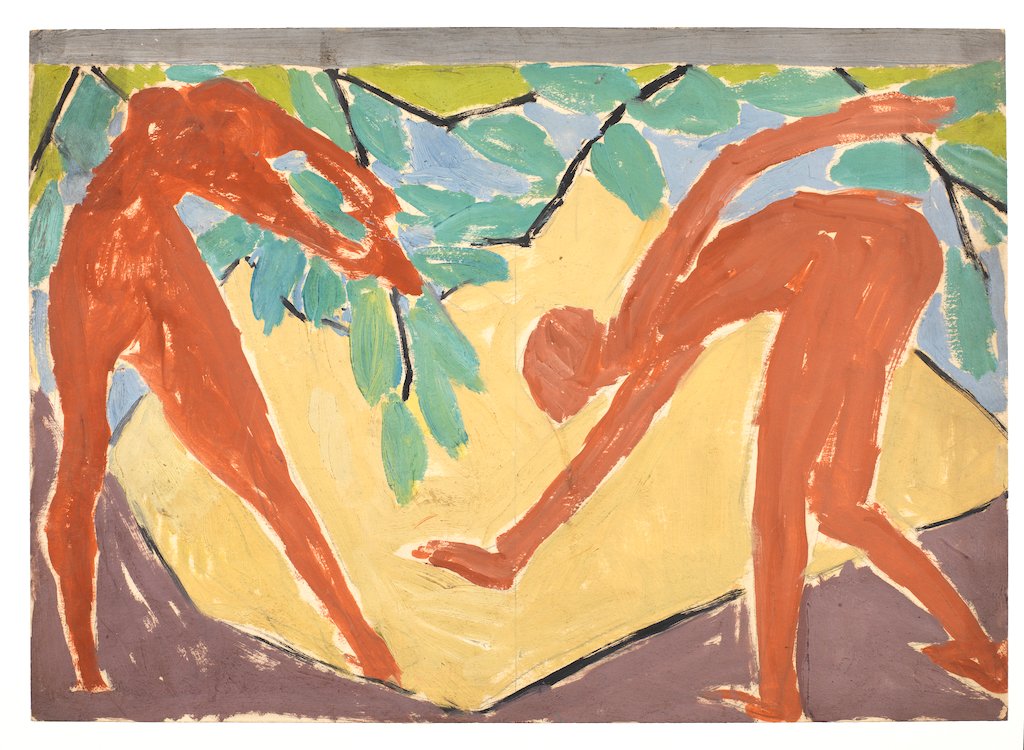

It also forms the backdrop to one of her most dynamic and “outrageously modern” designs – a screen featuring Adam and Eve having a ball in the Garden of Eden (main picture). Inspired by Matisse’s The Dance 1909 (that Bell would have seen at the Post-Impressionist Exhibition of 1912), it features the naked couple prancing about with unashamed delight in the freedom of their nudity. There’s no hint of shame and, perhaps more significantly, little differentiation between the man and woman. They are portrayed as equals, both involved in shaking the fruit from the tree.

It also forms the backdrop to one of her most dynamic and “outrageously modern” designs – a screen featuring Adam and Eve having a ball in the Garden of Eden (main picture). Inspired by Matisse’s The Dance 1909 (that Bell would have seen at the Post-Impressionist Exhibition of 1912), it features the naked couple prancing about with unashamed delight in the freedom of their nudity. There’s no hint of shame and, perhaps more significantly, little differentiation between the man and woman. They are portrayed as equals, both involved in shaking the fruit from the tree.

The screen was made for the Omega Workshops, set up in 1913 by critic Roger Fry in conjunction with Bell and the painter Duncan Grant to sell fabrics, furniture and other household items designed and made by artists. The aim was to blur the distinction between fine and applied art and to introduce brighter colours and radical designs to people’s homes.

Bell clearly felt freer to explore abstraction in her Workshop designs than in her paintings. Especially dynamic is her 1913-14 design for a rug. Thin black lines slice like blades through bands of ochre, green and grey as they jostle for position. The dynamism of the image is like a foretaste of the spiky angularity that would characterise the work of Vorticists like David Bomberg and Wyndham Lewis, both of whom were briefly involved with the Workshop.

On show are the covers Bell designed for her sister, Virginia Woolf’s books and the dinner service she produced with Duncan Grant for the art historian Kenneth Clark (pictured right: Virginia Woolf). It features portraits of 50 famous women including queens, courtesans, writers, artists, poets, dancers, film stars and Bell herself, most of whom had to defy social norms in order to pursue their goals and make their voices heard.

On show are the covers Bell designed for her sister, Virginia Woolf’s books and the dinner service she produced with Duncan Grant for the art historian Kenneth Clark (pictured right: Virginia Woolf). It features portraits of 50 famous women including queens, courtesans, writers, artists, poets, dancers, film stars and Bell herself, most of whom had to defy social norms in order to pursue their goals and make their voices heard.

Bell’s interest in design wasn’t limited to making products for sale. She and Grant turned Charleston, their mutual home, into a total work of art by painting every surface and filling the farmhouse with their own furniture, fabrics and paintings. In turn, her domestic environment weaves its way into her paintings; whether still lives, interiors or portraits, her pictures focus mainly on her friends, family and immediate surroundings, as though art and life were inextricably intertwined.

In her 1915 portrait of Mary St John Hutchinson (mistress of her husband Clive) this idea becomes palpable. Mary poses in front of an abstract painting coloured the same fleshy pink as her face and neck, so that sitter and ground fuse into a single surface. Meanwhile, patches of blue seem to have migrated from the edge of the backdrop to the sitter’s cheek, chin and the whites of her eyes as if to stress that the likeness is made of the same substance as the painting visible behind her.

One of Bell’s most memorable portraits is of Dr Moralt, who nursed her seriously ill daughter, Angelica back to health in 1919 and became a long term friend. Wearing a black hat and what looks like a bulky fur stole over a black jacket, she fills the frame. Bell abandons her favourite, autumnal colours – ochres, oranges, reds and browns – for an almost monochrome palette as though to emphasise the seriousness and importance of the doctor’s profession.

One of Bell’s most memorable portraits is of Dr Moralt, who nursed her seriously ill daughter, Angelica back to health in 1919 and became a long term friend. Wearing a black hat and what looks like a bulky fur stole over a black jacket, she fills the frame. Bell abandons her favourite, autumnal colours – ochres, oranges, reds and browns – for an almost monochrome palette as though to emphasise the seriousness and importance of the doctor’s profession.

Her 1923 painting of a seated nude emphasises the power and resilience of the female body. This woman is built to withstand anything that life can demand of her. Rather than being an object of desire, she is her own person – a tower of strength. All the women in Bell’s paintings, in fact, demonstrate a similar independence of spirit. The three figures in A Conversation, 1913-16 (pictured below right) are formidable presences. Engrossed in a discussion that is clearly urgent, they pay no heed to the viewer eavesdropping on their conversation.

This makes the self-portrait that Bell painted not long before her death in 1961 especially poignant, since she looks so frail and wan. ‘I am absolutely indifferent to anything the world may say about me,” she once declared defiantly, but now all the fight and joy seem to have gone out of her. A few years earlier she portrayed herself with paint brushes in hand, her body alert and questioning; now, like most female sitters before her, she appears passive – with no sign of any activity other than posing to be looked at.

This makes the self-portrait that Bell painted not long before her death in 1961 especially poignant, since she looks so frail and wan. ‘I am absolutely indifferent to anything the world may say about me,” she once declared defiantly, but now all the fight and joy seem to have gone out of her. A few years earlier she portrayed herself with paint brushes in hand, her body alert and questioning; now, like most female sitters before her, she appears passive – with no sign of any activity other than posing to be looked at.

Maybe she is anticipating her fate – the way she will be ignored or belittled as soon as she is dead, like most women artists who enjoyed success in their lifetimes. This retrospective is, though, the beginning of a process of reappraisal through which her contribution as an artist is being recognised once again.