What’s the deal with Leonardo’s harpsichord-viola? Why were Impressionists obsessed with the color purple? Art Bites brings you a surprising fact, lesser-known anecdote, or curious event from art history. These delightful nuggets shed light on the lives of famed artists and decode their practices, while adding new layers of intrigue to celebrated masterpieces.

Hôtel Biron in Paris’ seventh arrondissement is something a misnomer. Over the past 300 years, it has been an ambassador’s villa, the seat of a papal representative, a girl’s boarding school, and an artist’s commune. Today, it houses the Rodin Museum, its surrounding gardens offering visitors an island of green in the heart of the French capital.

When Henri Matisse moved into Hôtel Biron in 1908, the early 18th-century mansion was derelict. Moss covered the front steps, walls were faded yellow, and windows were hard to open on account of the flora pressed up against them.

The nuns were partly to blame. After converting it into a school in 1820, they’d sold it for parts. They stripped and flogged its mirrors, banisters, paneling, and any other symptoms of rocaille exuberance. The state kicked the nuns out in 1907 and the building’s liquidator offered cut-rate rent ahead of what seemed an inevitable demolition.

Rodin’s The Thinker in front of Hôtel Biron in 1957. Photo: Getty Images.

But where some saw squalor, artists saw cheap rent and dilapidated charm. Soon, Hôtel Biron was abuzz with a shabby clique of the city’s creatives.

Matisse was an early resident, moving in around 1906. Though well-regarded abroad, his reputation in France lagged behind his contemporaries and space in the mansion was the best he could afford for his fledgling art academy. Students arrived from the United States, Russia, Romania, and beyond. They took classes in a courtyard pavilion and slept in the attic. They complained, not about the living quarters, but that their teacher’s focus was too traditional.

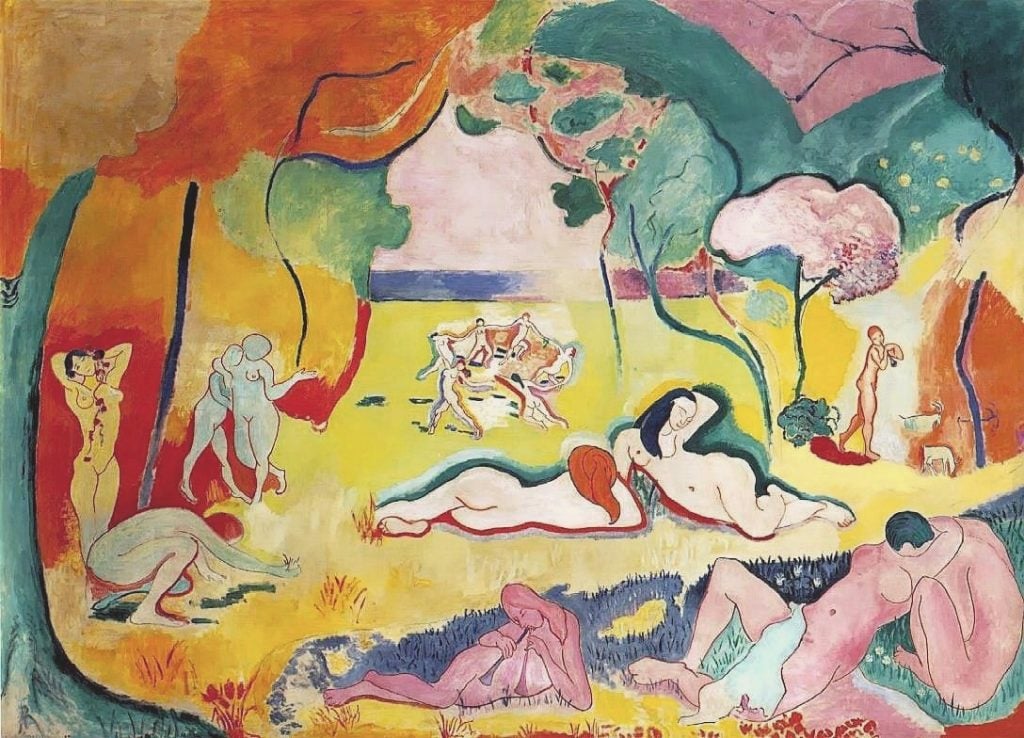

Henri Matisse, Joy of Life (Bonheur de Vivre) (1905–6). Collection of the Barnes Foundation.

A young Jean Cocteau happened upon the mansion’s garden while skipping school one day. To Cocteau, it seemed like something out of Baudelaire—he could see moonlit parties waltzing though the gardens and séances conducted in its darkened interiors. By evening, he’d installed himself in a second-floor room (he brought a piano). From his bedroom, Cocteau would launch Scheherazade, a magazine filled with contributions from Paris’ brightest.

The artists kept coming. Jeanne Bloch, a cabaret singer and cross-dressing comic actress, arrived. Edouard de Max, the tragedian actor known for his frequent partnerships with Sarah Bernhardt, moved into the chapel. Isadora Duncan, the American pioneer who helped unshackled ballet, found Hôtel Biron the ideal place for dance to meld with poetry and sculpture. German sculptor Clara Westhoff came along with her husband Rainer Maria Rilke—though unlike his sociable neighbors, the poet kept largely to himself.

Poet Rainer Maria Rilke with his wife, sculptress Clara Westhoff, circa 1910. Photo: Keystone/Hulton Archive/Getty Images.

The arrival of Auguste Rodin cemented the mansion’s reputation. By this stage in his career, Rodin was affluent and celebrated as the era’s greatest sculptor. He scattered his works around the garden and since he already boasted a production base in Meudon, he converted the first-floor rooms he took into a showroom to host collectors and journalists. The salon was sparse, nothing more than a table, bowl of fruit, and a Renoir painting.

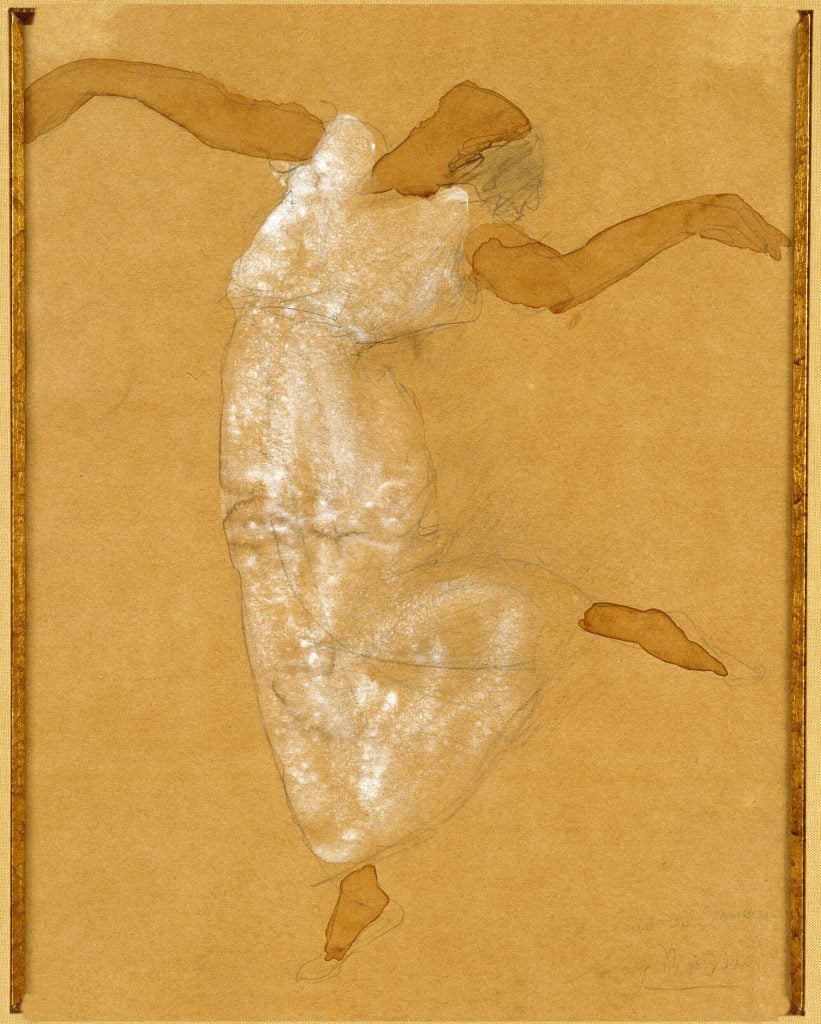

Auguste Rodin, Isadora Duncan (ca. 20th century). Photo: Universal History Archive/Universal Images Group via Getty Images.

Rodin filled the quiet with Gregorian chants flayed on a gramophone and liked to watch his young contemporaries dance and sing and party. Hôtel Biron offered Rodin an escape, a place of reprieve far from the demands of the public. Once he took over the entire building in 1917, however, he worked to turn it into a museum, a place the public could find him and all of his masterpieces.

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to get the breaking news, eye-opening interviews, and incisive critical takes that drive the conversation forward.