The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s exhibition Mary Sully: Native Modern (until 12 January 2025) features a recently rediscovered trove of works by the self-taught Yankton Dakota artist. In her lifetime, Sully produced drawings imbued with humour, wit and political and social critique that went unseen for decades—until her great-nephew brought them out of his mother’s basement and into the world.

Sully was born Susan Deloria (later taking her mother’s name) on the Standing Rock Reservation in 1896, one of two daughters of an Episcopalian minister. She descended from a strong artistic lineage: granddaughter of Alfred Sully (an American Indian Wars general and artist) and great-granddaughter of the 19th-century portraitist Thomas Sully, who was known for painting the Andrew Jackson likeness that would later be used for the $20 banknote and for his 1838 portrait of Queen Victoria. Unlike these predecessors, Sully was reclusive and suffered from anxiety disorders that stunted her own professional pursuits.

As an adult, Sully was primarily supported by her sister, Ella Cara Deloria, a linguist and scholar who worked with the anthropologist Franz Boas and is known as the first Native American woman ethnographer. Sully’s sister is represented in the Met’s show with her 1944 book Speaking of Indians, which examines the assimilation of the Dakota people and features cover art by Sully. Although the sisters struggled financially, they travelled and lived throughout the US—including New York, where Sully began her Personality Prints series, which make up the majority of the approximately 200 works in her surviving archive.

The aforementioned series comprises 134 vertical triptychs that show an abstracted version of a subject like Babe Ruth, Gertrude Stein or Fred Astaire. The top panels all have some metaphor to the subject, the middle have abstract geometric patterns (some with the markers of commercial prints) and the bottom panels vary widely—some have layers of Native American designs while others are purely abstract. In this series and other works, Sully explores the syncretism of her heritage and her contemporary influences, sourcing many subjects from mass media.

Sully is thought to have stopped making art around the mid-1940s. Her works were stored in a box after she died in 1963 in Omaha, Nebraska, and were passed down through the generations after her sister’s death in 1971. In the mid-1970s, Sully’s works came to the attention of the artist’s great-nephew, Philip J. Deloria, whose mother had stored them in their basement. In the mid-2000s, he began looking at the drawings more closely.

Deloria, a history professor at Harvard University, first presented Sully’s images in 2008 in a conference organised by the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian and the National Gallery of Art. He spent the next decade documenting the works for his 2019 book, Becoming Mary Sully: Toward an American Indian Abstract. He set up the Mary Sully Foundation in 2023, from which the Met acquired 12 works and was gifted seven last year.

The Met’s associate curator of Native American art, Patricia Marroquin Norby, co-curated the exhibition with Sylvia Yount, head curator of the museum’s American Wing. Norby tells The Art Newspaper that the term “Native Modernism” has been “typically placed in the context of the Southwest or the Plains, and it’s a label that’s largely attributed to painting and sculpture”. She adds that the schools associated with the movement were “primarily started by non-Native people, and had the influence of an aesthetic meant for non-Native people. With Sully’s cache of works being discovered, that previous narrative is entirely blown out of the water. Because she worked in isolation, she was not only working within her own ideas and aesthetics but also developing an intercultural visual language that’s completely her own.”

Below are four key works by Sully from the Met show.

Courtesy the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Three Stages of Indian History: Pre-Columbian Freedom, Reservation Fetters, the Bewildering Present (around 1920s-40s)

In Deloria’s book, he describes the panels in this work as a “signifying abstract”, a “geometric abstract” and an “Indian abstract”. This is one of Sully’s more outwardly political pieces. The top panel contains four scenes, beginning with feet crushing suffering silhouettes and descending to a fenced-in reservation and a pre-colonial Native American community. The middle and bottom panels abstract the four scenes with geometric patterns, reducing the images to colours and shapes evoking Native American weavings and beadwork.

Courtesy the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

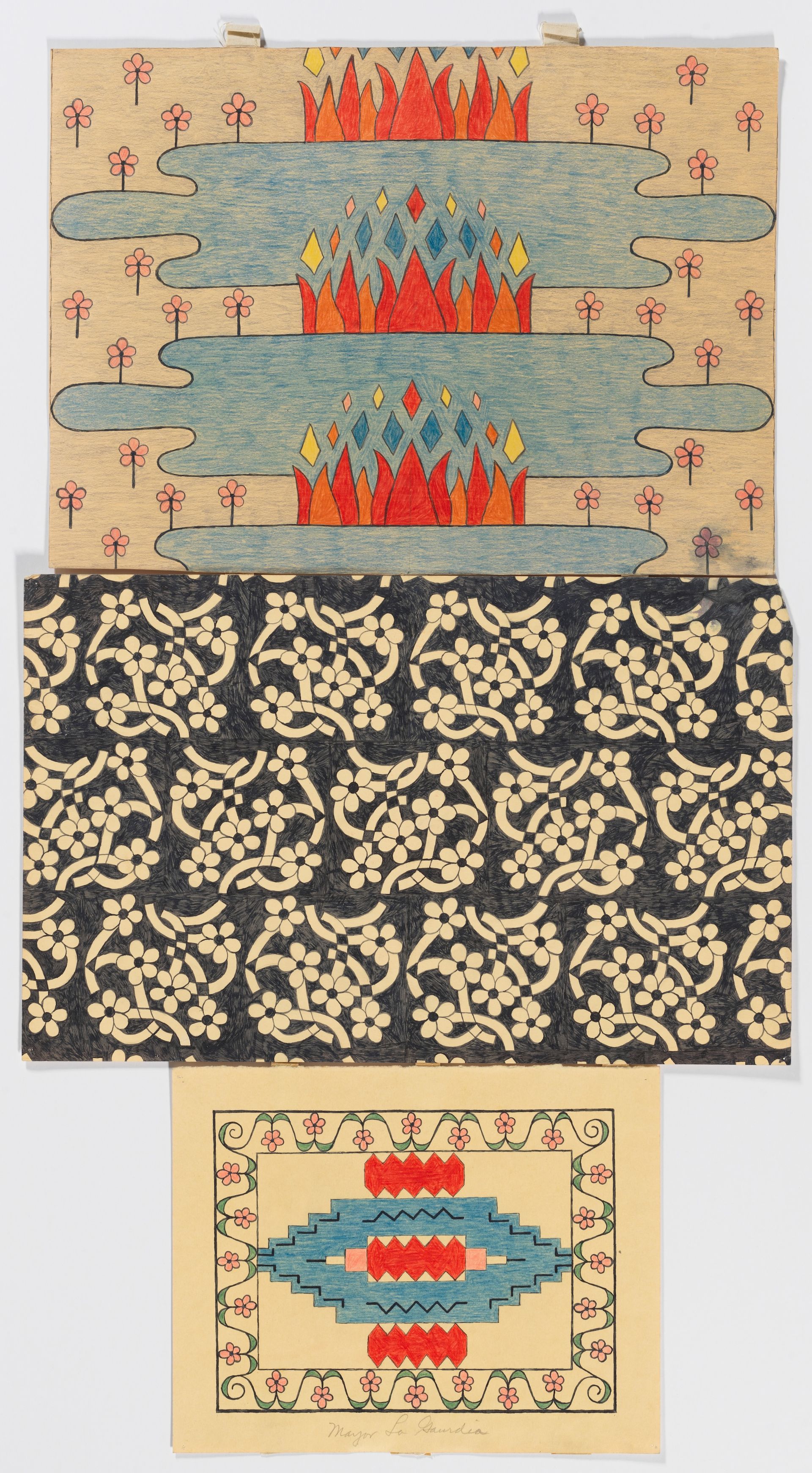

Fiorello La Guardia (1882-1947) (around 1920s-40s)

Sully, like her great-grandfather the portraitist, was enraptured with celebrity—a world she was detached from but observed via magazines like Life and Good Housekeeping. Some of her works, however, suggest that she also took inspiration from real-life experiences, like living in New York. In this “personality print”, she represents the New York politician Fiorello La Guardia, adorning his three panels with floral patterns in reference to the meaning of his first name in Italian, “little flower”.

Courtesy the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

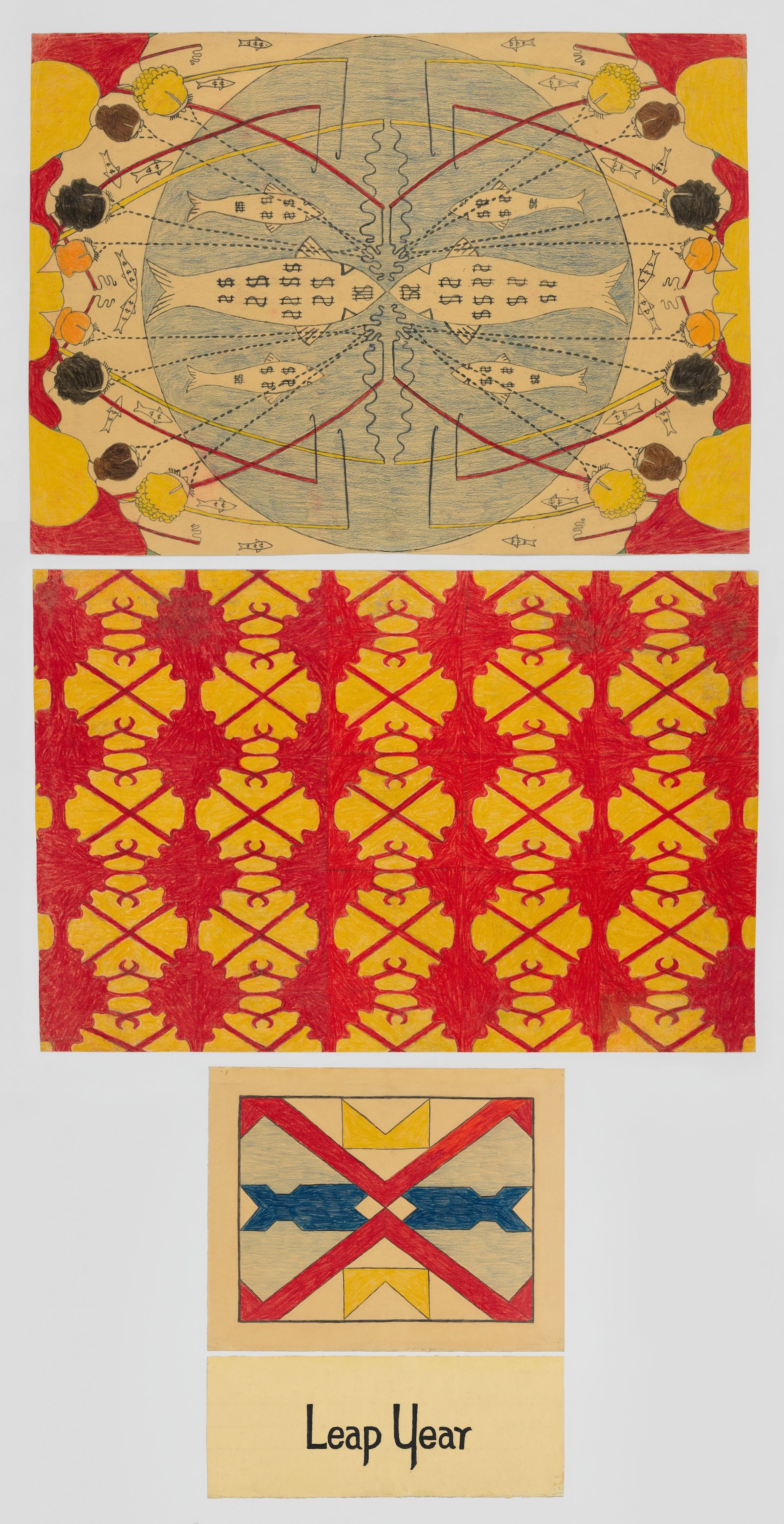

Leap Year (around 1920s-40s)

Many of Sully’s works take a unique approach to perspective, oftentimes presenting subjects from an aerial view. In this one, Sully draws women wielding fishing poles, each attempting to catch the biggest or “richest” fish and overlooking the smaller, more accessible ones branded with fewer dollar signs. In the subsequent panels, she abstracts the image with kaleidoscopic effects. The work encompasses humour, social critique and romantic relationships—a theme also visible in pieces like Lunt & Fontanne, a floral work that references a famed Broadway couple believed to have had a lavender marriage.

Courtesy the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

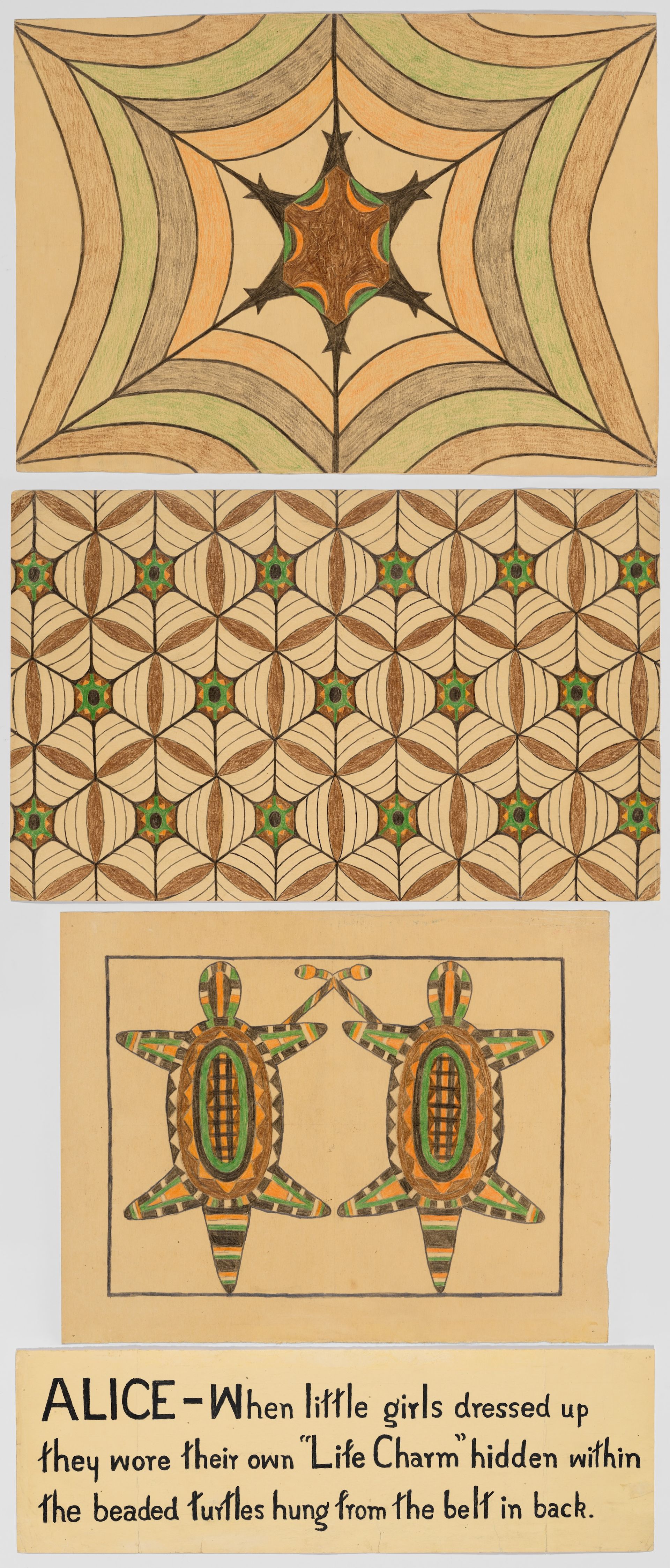

Alice (around 1920s-40s)

A centrepiece of the Met’s exhibition, this work features a series of turtles representing young girls. When a Dakota child is born, their umbilical cord is traditionally placed inside an amulet, with girls receiving containers shaped like turtles and boys getting lizards. The amulet could be worn on a dress, belt or sash, symbolising that the child will never become disconnected from their community or family. In this work, the two turtles tethered together by their umbilical cords perhaps reference Sully’s close relationship with her sister, the earliest and only known proponent of Sully’s art practice in the artist’s lifetime.

- Mary Sully: Native Modern, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, until 12 January 2025