Norman Cornish from Spennymoor and L.S. Lowry from Salford both became acclaimed documenters of northern working-class life in the 20th century. It makes sense then to put examples of their work together in a joint exhibition. This was done many years ago in the late 1960s when the Stone gallery in Newcastle put on a joint exhibition, and the Bowes Museum at Barnard Castle, has done it again in an exhibition entitled Kith and Kin, which runs until 19 January next year. It is an exhibition that raises a number of questions both about the work of the artists themselves and how we remember the north of England, while going forward into the future.

Who were Norman Cornish and LS Lowry?

Norman Cornish was born in 1919 and joined the Spennymoor Settlement at the age of 15, where his natural talent as an artist was encouraged by the leader of the Settlement, Bill Farrell.

It has been said of Cornish that, “essentially self-taught, one of the very few lessons he took on board in his formative years came courtesy of a firm directive from the inspirational warden of the Settlement, Bill Farrell, who told him: “Draw what you see and paint what you know.””

Cornish was also a miner in the local Dean and Chapter Colliery for 33 years, before becoming a full time artists at the age of 46. This is important to remember as his insider status is very much displayed in his work. This is in sharp contrast to Lowry.

Lowry was born about 30 years before Cornish in 1887, in Stretford to a father, Robert, who worked as a clerk in an estate agent’s office, while his mother, Elizabeth, was a talented pianist. It has been noted that “for a time the family lived in Victoria Park, a leafy suburb of south Manchester, but in 1909 they moved to Pendlebury, an industrial area between Manchester and Bolton. At first Lowry hated it, but his surroundings gradually fascinated him. By the 1920s he was painting and drawing the industrial landscape around him.”

Lowry came from a more middle-class background than both Cornish and many of the subjects he painted in and around Manchester and consequently was an outsider, who painted with a greater sense of detachment than Norman Cornish 100 miles to the north east in Spennymoor.

How is their work similar?

The reason why the art of Cornish and Lowry is often compared and has been put together in more than on exhibition is simple; they both documented northern working class life in the 20th century. Both celebrated the ordinary, the mundane, some might even say the drab, but in so doing turned them into something special, something to be respected, as we develop empathy with the subject matter.

Both artists were fascinated by their surroundings and the communities that sustained them. Cornish and Lowry documented two of the world’s first great industrial communities, just as they were entering into a long decline and changes that are still resonating with us today.

Both men also painted the North East, even though Lowry is best known for his work in the North West. Cornish concentrated his work in and around Spennymoor, while Lowry, fascinated by the North Sea coast worked in places such as Berwick, South Shields and Sunderland.

How is their work different?

But there are some important differences between the work of the two men, which the exhibition at Bowes Museum rightly highlights. The main difference goes back to the status of the two men within their communities as mentioned earlier. Cornish was a miner for 33 years and was very much part of the community which he documented in his work.

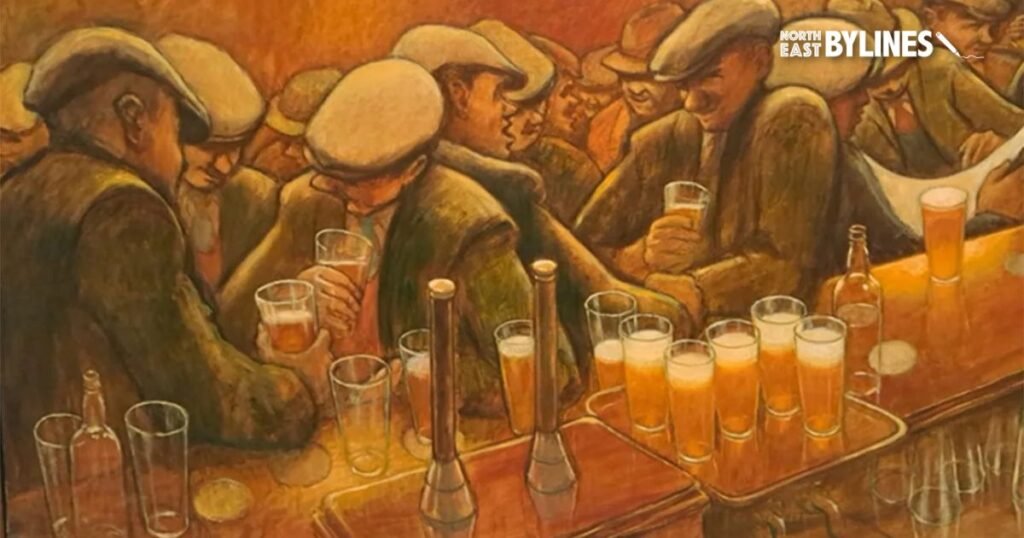

Consequently, there is a warmth and a familiarity in his work, which takes the viewer of the art into his pictures. When one sees a painting such as Busy Bar, you are drawn into the work, wanting to overhear the conversations and perhaps even join in.

By way of contrast Lowry was an outsider and consequently his work is more detached. He used his imagination more and would put people together from different times in the same scene. While Cornish was fascinated by the shapes of people and scenes around him, Lowry was often more fascinated by the overview of the places he painted.

There is another important respect in which the work of Cornish and Lowry differs, while representing two different strands of the northern experience in the 20th century. As in insider, Cornish painted many scenes involving working miners, emphasising both the difficulty of the job and the dignity of work.

On the other hand, in his more detached way, many of the subjects of Lowry’s paintings are seen hanging round in streets and are often assumed to have been unemployed, especially in those works from the 1930s. The difficulties of hard, skilled, manual work and the indignity and despair of unemployment were both vital parts of the northern experience, especially for men, in the 20th century. It is somehow appropriate that these two major artists have through their differences been able to bring both parts together and the exhibition manages that very well.

Remembering the north

This brings us round to questions of how we can use the work of both men to remember the north that they knew, a place that is in many respects now gone. In his review of the same exhibition North East writer Dan Jackson had this to say:

“How, then, might we assess the progress of the north of England since the days of Lowry and Cornish? The North East in particular has had a difficult last century, with only sporadic interludes of confidence and prosperity — notably in the fifties. It now has among the very worst health, education and employment outcomes in the country.

“By stirring our collective memory, the Kith and Kinship exhibition reminds us of what community life in the North East was and could be again. The challenge for anyone concerned about the region’s future is not to recreate the past, but to convey its history to inspire a new generation of community builders.”

This seems to me to be entirely correct. Sometimes it can seem that we are too nostalgic in the North East, for a region that never really was. If we are not careful, while a trip to Beamish Museum in County Durham, or to Woodhorn Colliery in Northumberland can give us a reasonable idea of what life was like in the region’s industrial heyday, there can be something missing from the experience; the hardship and the struggles that people went through both individually and collectively. It is not always easy to recreate these in a museum, but perhaps looking at the work of Cornish and Lowry can fill that gap, and it is surely important that both aforementioned museums do represent the work pf people like Norman Cornish and the Ashington Pitmen painters in Northumberland. Life in the industrial north was often hard and dangerous and people did struggle, and we shouldn’t always view it through rose-tinted spectacles.

It is vitally important to remember our heritage in the North East and across the wider north, but we should avoid becoming too backward looking. As the late North East born agony aunt Denise Robertson put it one way of dealing with history is to think about how you drive a car; you ned to keep your eyes on the road ahead, but at the same time you need to refer to you rear view and wing mirrors from time to time as well. We do need to look ahead in the North East, but use the work of people like Cornish and Lowry to remind us of how we got to where we are now. Similarly, Jackson is right to suggest that the work of people like Cornish and Lowry should inspire is to build a better future.

Dealing with a past that is gone – what can we learn for tomorrow?

So how can we learn from a past that is now largely gone? We can learn that we want to build a north which respects people and the warmth of community and the dignity of work as Cornish’s art shows so graphically. Similarly, we need to avoid the fate of so many of Lowry’s unemployed characters, while keeping the humour he reflects so well in his work.

We need to respect our heritage and take the positive things forward; this can include the community spirit and the passion for technological innovation which so clearly mark our heritage, while remembering that our industrial work in the future will be different and greener. Additionally, the work of both Cornish and Lowry in their own ways, acts as more evidence as to why we should have a just transition to the new, greener economy, in both the North East and the wider north.

This is an important exhibition as we consider how we deal with our past across the north and decide on how our future should look as we move further into the 21st century. Despite some differences, both Cornish and Lowry have left valuable documentation of how the north we know today was forged and how we got to where we are now. Perhaps we now need another generation of artists to reflect our communities as Cornish and Lowry did and to imagine what our individual and collective futures might look like.

For more details of how to visit the Kith and Kin exhibition at Bowes Museum please see here.

CLICK HERE TO DONATE TO OUR CROWDFUNDER AND GIVE CITIZEN JOURNALISM A BOOST!