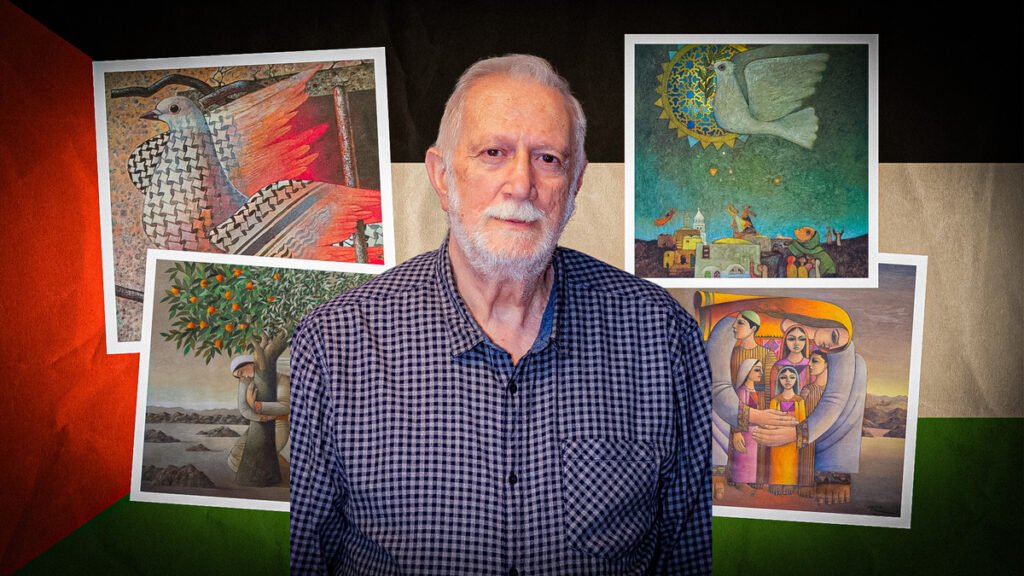

Palestinian artist Sliman Mansour reflects on the impact of the Gaza war, the life and legacy of his friend Fathi Ghaben, and the role of art under occupation.

Since the start of Israel’s war on Gaza, Palestinian artist Sliman Mansour has had trouble focusing on his work.

“I haven’t been able to produce much art,” he tells The New Arab. “I have only made three or four paintings in the last couple of months. Usually, I do much more, but then I listen to the news and it becomes hard to concentrate.”

It was only at the end of February that Sliman Mansour’s friend and colleague, Fathi Ghaben, died after Israeli authorities did not allow him to leave Gaza to receive medical help.

Ghaben, like Mansour, was a renowned Palestinian artist, and aside from their love of art, the two friends also had other things in common.

Both were born a year before the declaration of the establishment of Israel and Israeli authorities have imprisoned both throughout their lives because of their paintings which address Palestinian identity.

“I have been detained twice in my life, but only for two to three weeks each time; they just kept me for interrogation. Fathi, on the other hand, spent three months in prison because he had painted his nephew, who Israelis had killed. He was still a boy.

“Fathi painted him wrapped up in the colours of the Palestinian flag. So, they confiscated the painting with a couple of other artworks and imprisoned him,” Sliman tells The New Arab.

“The Israeli court gave him a prison sentence of six months. I, along with other artists, demonstrated against the court’s decision, and they finally agreed to let him out after three months under the condition not to repeat his actions. I think that was in 1983.”

The shift in colours: Art during the war

The few paintings Mansour has produced since the war are less colourful than before.

A couple of months ago, the 77-year-old artist held a group exhibition in Ramallah and realised that most of his colleague’s paintings also contained more grey tones.

“The paintings used to be more colourful before the war, maybe because we were more hopeful then,” he says.

The artist, who must go through time-consuming and humiliating checkpoints every day to get to his studio in Ramallah, still wants to convey hope with his art, even if it seems difficult now.

Symbol of Hope, one of Mansour’s most famous artworks from 1985, shows the residents of a Palestinian village looking up to the sky and seeing a dove of peace.

Framed print versions are seen often in Palestinian cafés and bookstores in East Jerusalem, where Mansour lives.

“The Israeli government’s main aim is to take our hope from us and dehumanise us. But we hope to live in this land peacefully and freely, with the same rights,” Mansour explains.

“The only way you can fight these campaigns of dehumanisation is through art and culture,” he continues.

During the First Intifada, Mansour started using mud for his artwork, as he took part in demonstrations.

When I mention to him that he has also lived through the previous Israeli wars, he laughs. “Yes, just my great luck.”

Nevertheless, he believes there has never been as much hatred in society as today and Mansour senses the constant tension.

“Of course, the situation was always tense, but now the tension has increased,” the artist says.

“When I am in Jerusalem, I feel less comfortable. Even if I am just in the hospital, I feel it. Recently I wanted to take a shorter route to my studio in Ramallah from Jerusalem, but we missed a sign because it was dusty and dark. We were warned by other Palestinians that the Israeli military might shoot us if we went further because they had closed the street. So, even if you make a small mistake, you might end up dead for absolutely nothing,” he explains.

The role of art in serving the community

For Sliman Mansour, it is important to depict his living environment in his pictures. Today, he notices that many artists are adapting to a certain trend without having a personal message.

He believes it is important to be inspired by different styles, but many gallerists in Israel deliberately exhibit abstract art to avoid the political reality.

Mansour explains that one doesn’t have to talk about war or occupation in every piece of art one creates. But he finds it bizarre when a Palestinian artist never talks about the political reality he lives in.

“As an artist, you have to be honest with yourself and with what’s happening around you and react accordingly. You shouldn’t forget about the lives of your friends and the lives of everybody around you. If you are ignoring things like occupation, then you are taking a political position to get away from the people and not deal with the real issues,” he says.

“For me, it’s a political decision. Of course, if you do artwork that deals with your life under occupation, then people will say you are doing political art. But if you ignore this fact and these problems, it is not less political.

“It is political art based on forgetting everything happening around you. People might love your art anyway, especially the art galleries. They might exhibit your work if you try to copy the trend of the museums in New York or Berlin. But you will ultimately lose the connection to local artists and the people around you. Art should serve one’s community,” he concludes.

Elias Feroz studied Islamic religion and history as part of his teacher training programme at the University of Innsbruck in Austria. Elias also works as a freelance writer and focuses on a variety of topics, including racism, anti-Semitism, Islamophobia, the politics of history, and the culture of remembrance

Follow him on X: @FerozElias