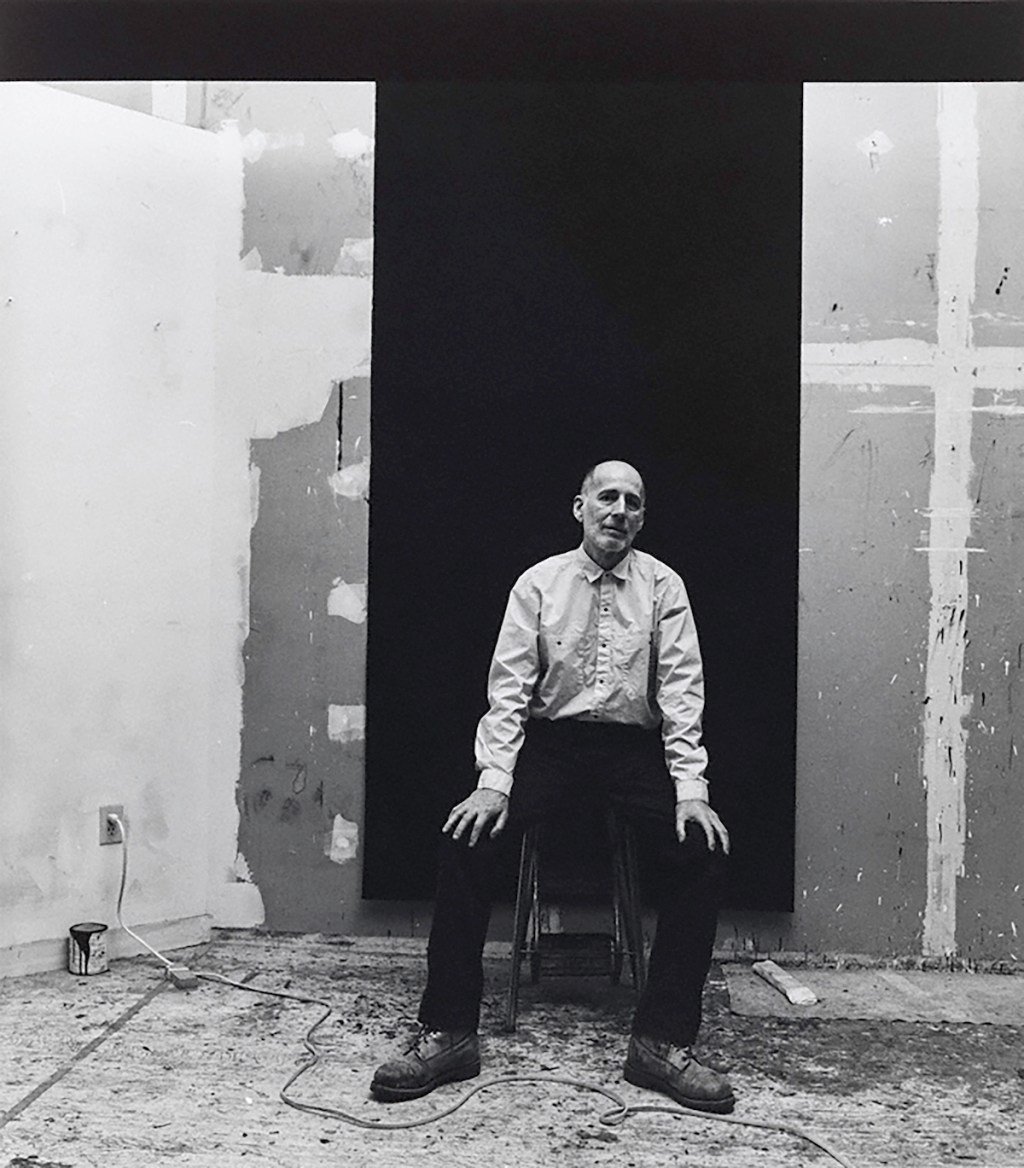

Photo Arnold Newman/Getty Images/Courtesy Moskowitz Studio and Peter Freeman, Inc.

Robert Moskowitz, an acclaimed New York–based painter known for crafting spare, mysterious images that flit in and out of recognition, has died at 88. His New York gallery, Peter Freeman, Inc., confirmed his death on Wednesday, saying that he had been battling Parkinson’s.

Many critics have attempted over the years to peg Moskowitz’s work to a particular movement, noting his work’s similarities to movements like Pop and Minimalism, as well as a figurative painterly mode that emerged during the 1970s. But Moskowitz’s work conformed to no dominant aesthetic style, flirting with what was en vogue and then subverting it.

He frequently painted pictures which include familiar symbols and imagery: New York’s skyline, Rodin’s Thinker, a baseball, a windmill. Moskowitz would represent these things only as silhouettes, often cropping out certain elements in the process, abstracting their forms, and setting them against fields of color. These paintings are imbued with a sense of loss that is palpable, even if there is no death imagery represented.

His most famous work, Swimmer (1977), features a bather moving across a plane of Prussian blue. One arm and part of a head are visible, but the rest of this swimmer’s body are hidden away beneath the surface. Where the swimmer is headed is left ambiguous, since there is no geographical information to be gained. Moskowitz’s subject appears lost, forever traveling.

Today, Moskowitz is most commonly aligned with New Image Painting, a tendency formalized by a 1978 Whitney Museum show of the same name. The exhibition surveyed artists whose imagery “is radically manipulated through scale, material, placement and color,” allowing it to be “released from that which it is representing.” Moskowitz figured in the show alongside Jennifer Bartlett, Neil Jenney, and Susan Rothenberg, all of whom rose to fame at a time when both figuration and painting had been pronounced dead by many critics.

“I always have an image. I might not know exactly what it means, but you could say the image is the idea,” Moskowitz said in a 1988 interview. “First, it’s intuitive—I’ll want to paint a particular image. Later, I find out what the image means to me, usually after the painting is finished. I’m never quite sure why I realize one image or another.”

Moskowitz died just days after his latest solo exhibition went on view at Peter Freeman, Inc. There, he is showing paintings made over the past four decades that contain an array of imagery: the Flatiron Building, red crosses, a diver culled from a ceiling fresco in Pompeii.

Robert Moskowitz’s current show at Peter Freeman, Inc. in New York.

Photo Nicholas Knight/ Courtesy Moskowitz Studio and Peter Freeman, Inc.

Robert Moskowitz was born in 1935 in Brooklyn. Moskowitz’s father, a Jewish dry cleaner, left his wife and children 13 years later. Moskowitz’s mother could not support the family in New York, and sometimes took work in Florida to make money. Robert ended up having to look after his youngest sister Karen alongside his teenager sister Elaine.

Initially, Moskowitz did not intend to become an artist, instead entering an engineering program at the Mechanics Institute of Manhattan. But after he was pushed toward becoming a technical illustrator once he entered the workforce, he ended up attending the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, where one of his instructors was the famed Abstract Expressionist painter Adolph Gottlieb. That ended up becoming one of many key connections to various artists established by Moskowitz, who worked as an assistant to photographer Walker Evans later in his career.

Moskowitz’s big break came following his inclusion in the 1961 Museum of Modern Art show “The Art of Assemblage.” In 1962, Moskowitz had a solo show at Leo Castelli Gallery, where he exhibited a series of paintings that featured real shades. He was playing, he said, on the notion that painting offered a window onto the world—and gently needling that centuries-old idea, since the shades didn’t reveal much behind them. In 1983, art historian Robert Rosenblum remarked, “They seemed to push both the basic language of painting and the fundamentals of image-making to a rock-bottom economy, where suddenly the two worlds were forever fused — a flat painting equaling a flat window shade.”

Robert Moskowitz, Untitled, 1961.

Photo Nicholas Knight/Courtesy Peter Freeman, Inc.

Critics greeted the Leo Castelli exhibition rapturously, with some comparing the work to Jasper Johns’s art of the era. Those comparisons seemed particularly apt once Moskowitz introduced small replicas of everyday objects in his paintings, producing, for example, a 1964 work paying homage to John F. Kennedy that featured a tiny rocking chair. But that same year, Moskowitz had exited Castelli’s roseter, perceiving an unwillingness on the dealer’s part to exhibit “a slower kind of painting.”

That slower kind of painting was something Moskowitz went on to practice. To craft it, he drew on his studies with a Zen master, something he had been undertaking for years. “The only thing that is clear to me about Zen is sitting to look at yourself—looking inward,” he said. Yet as he was working toward a new kind of painting, he also struggled financially, having fallen out of favor with critics. After the “New Image Painting” show at the Whitney, however, he once again found acclaim.

In 1988, Moskowitz received a mid-career survey with the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden in Washington, D.C.; the show went on to travel to the La Jolla Museum of Contemporary Art and the Museum of Modern Art. “It’s both difficult and educational to see your life in front of you like this,” he told the New York Times in 1989, the year of the MoMA iteration of the show, speaking from the Tribeca loft where he lived with his wife, the painter Hermine Ford, and his son Erik.

Robert Moskowitz, Falling Leaf for Louis Moskowitz, 1974.

Photo Nicholas Knight/Courtesy Peter Freeman, Inc., New York

Moskowitz would return to his familiar motifs over the years, but his imagery lost none of its impact. In 2016, when he staged a small show of new works at New York’s Kerry Schuss Gallery, critic Barry Schwabsky wrote in Artforum that these works were “probably among his best, and, for that matter, are among the best anyone is making today.”

Yet Moskowitz remained modest about his work throughout this career. He once said, “Art can be like nature, and as an artist you become part of nature and the world. Maybe that is in my work as well.”