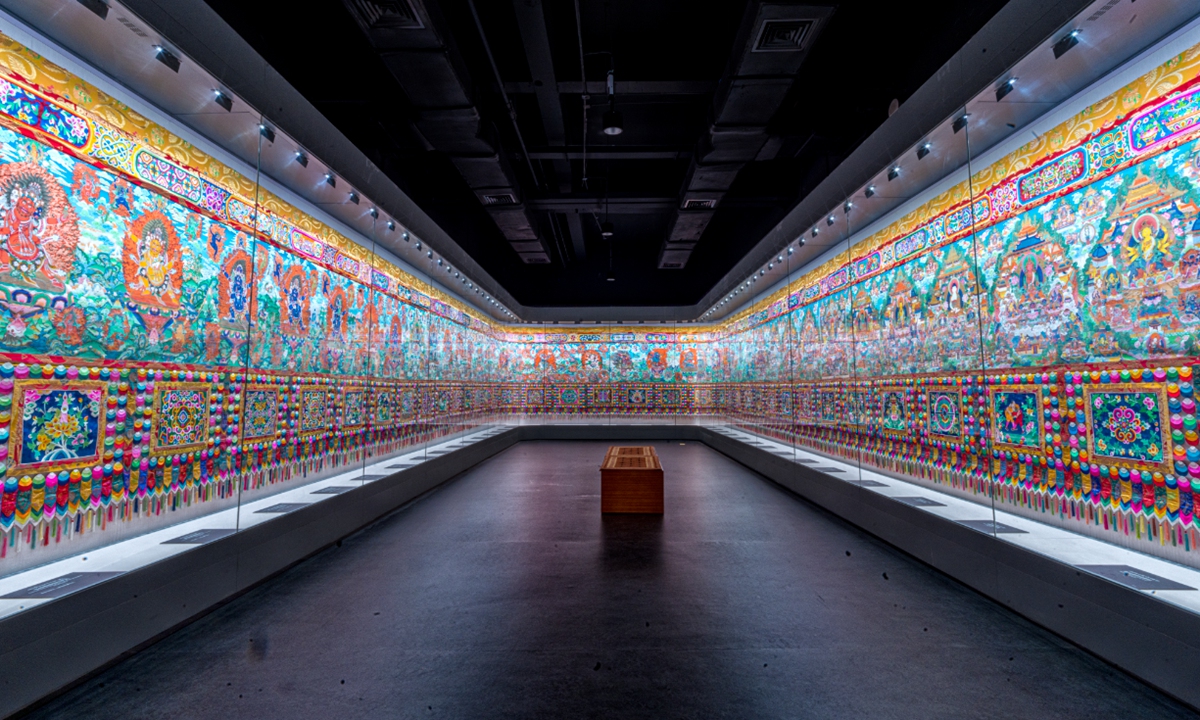

Thangka works at the Qinghai Tibetan Culture Museum in Xining, Northwest China’s Qinghai Province Photo: VCG

Editor’s Note:

The Yellow River, which began to form 1.25 million years ago, gave birth to the roots and soul of the Chinese nation. As it meanders through nine provinces and autonomous regions, the river not only shapes breathtaking natural landscapes but also nurtures the core wisdom and cultural richness of the nation. The intangible cultural heritages that have developed along the Yellow River – ranging from the Regong arts of Qinghai Province to the Weifang kite-making techniques of Shandong Province – serve as compelling evidence. In this series, the Global Times culture desk will guide readers through China’s most celebrated traditions that have flourished alongside the river, offering a glimpse into the pure essence of Chinese culture and how it continues nourishing contemporary life.

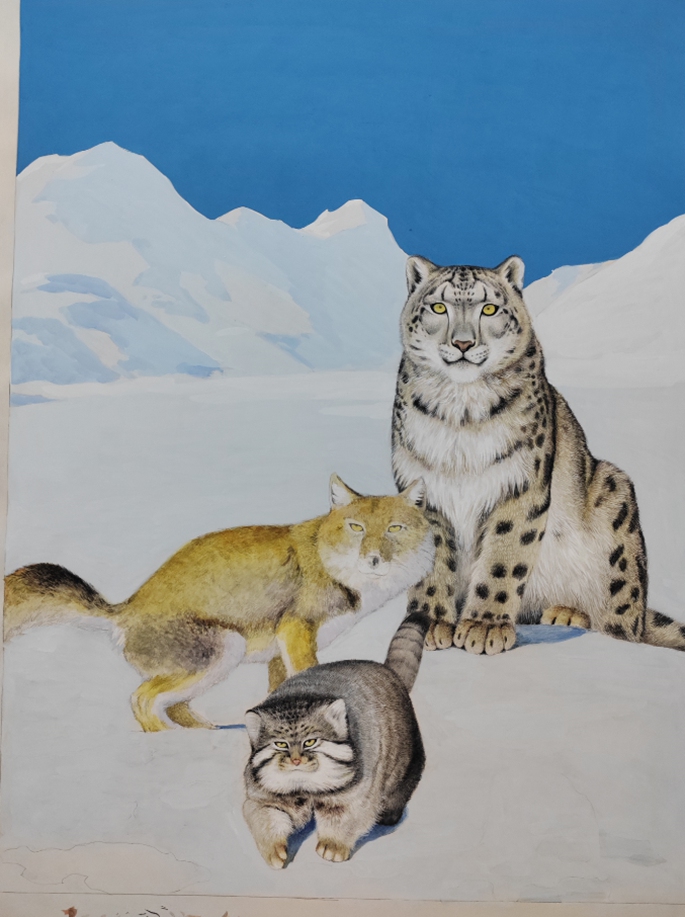

One of Fan Qingji’s works Photo: Courtesy of Fan Qingji

These days, Fan Qingji has been exceptionally busy. With the arrival of another harvest season, the villages across Tongren in the Huangnan Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture in Northwest China’s Qinghai Province are bustling with activity. As the crops ripen, people don the traditional attire of the Tibetan ethnic group, adorn themselves with jewelry, gather in the village courtyards, beat hand drums, and perform ritual dances to rhythmic drumbeats.

Having lived here to learn thangka art for 14 years, Fan has integrated well into the vibrant atmosphere of the plateau’s grand “Regong June Festival.” As an artist specializing in thangka that are usually painted on cotton or silk, he is now adept at meticulously painting thangka motifs onto the villagers’ hand drums, contributing his artistry to the joyful celebrations.

In the high valleys of southern Qinghai, the Longwu River rushes from south to north, cutting through mountains and gorges before joining the Yellow River. This river, a tributary of China’s “Mother River,” has long nourished the communities along its banks. This region is called “Regong,” which in Tibetan means “golden valley,” and is the birthplace of the rich artistic tradition known as Regong art. Among its many forms – from murals and embroidery to sculpture – thangka painting stands out, revered both for its spiritual significance and artistic complexity.

While the art of Regong thangka originated at the source of the Yellow River, Fan hails from East China’s Shandong Province, where the Yellow River meets the sea. Tracing the river upstream, Fan arrived in Tongren in 2011. He was instantly captivated by the rich and vibrant artistry of thangka painting, and decided to put down roots here. Day after day, he practiced outlining, tracing, and coloring, absorbing the essence of Regong thangka art.

Fan told the Global Times that the Yellow River cultural genes flowing in his veins is continually merging with the centuries-old tradition of Regong thangka in culture of Tibetan ethnic group, providing a deep wellspring of inspiration and support for his artistic journey.

Currently, there are around 30,000 artisans just like Fan engaged in thangka creation, inheriting skills passed down through generations. It is no exaggeration to say that in the Regong region, “every household has a painter, and everyone knows how to paint.” In 2009, Regong art was inscribed on the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity by UNESCO, following its inscription in China’s national list of intangible cultural heritage in 2006.

For Niangben, a thangka painter as well as a national inheritor of Regong art, the path to the mastery of this art has been a long journey. These painters’ stories with Regong thangka usually begin with preparing cloth and grinding pigments, then move on to color mixing, base layers, shading, line work, gilding, and finally, the delicate “eye-opening” that animates each figure. “Most importantly, you need to maintain inner-peace and stability before everything starts,” Niangben told the Global Times.

One of Niangben’s works Photo: Courtesy of Niangben

The art of color

When Fan first began learning thangka, he practiced line drawing every evening, a habit he still maintains, sketching outlines both morning and night. His days were devoted to learning how to apply base colors, dyes, adding gold detailing, and enhancing lines. Fan spent over two years mastering just the techniques of outlining and gold application, dedicating more than eight hours a day to studying the art.

Once he had established a solid foundation in sketching, Fan moved on to mastering the soul of thangka art – coloring. Having majored in oil painting at university and later working in an animation company, he already possessed a strong background in painting. Yet, he still had to repeatedly learn how to fill in thangka paintings with mineral pigments. During this process, Fan, echoing Niangben’s words, found a way to truly settle his restless mind and maintain inner peace. This balance of visual pleasure and spiritual tranquility deeply fascinated him.

Looking back on the past 14 years, Fan said he feels as though he has been swimming in an ocean of colors. He has come to realize that creating thangka requires one to fully unleash their imagination while strictly adhering to tradition.

Regong thangka painting follows time-honored practices, using only the finest materials. Artists employ precious minerals such as gold, silver, turquoise, and malachite, as well as plant-based pigments from saffron, rhubarb, indigo, and more. These are painstakingly ground together with other substances like animal glue and wheat juice until the pigments reach a creamy consistency suitable for painting. This results in natural colors that are vivid, rich, and enduring and resistant to decay and insects so they retain their brilliance for centuries.

The techniques of hand-painted thangka are predominantly meticulous and richly colored, though some pieces may be more expressive or rendered purely in line art. The process is highly intricate, involving the selection of canvas, preparation of the mounting, sizing, polishing, correcting linework, sketching, drawing facial features, and finally mounting the finished work. Creating a superior thangka may take several months, or even years, to complete. “Every step tests skill and patience,” said Niangben.

Niangben noted that the use of colors in thangka is inseparable from the local environment. The Longwu River, the mountains, and people’s daily life are reflected in its imagery, linking spiritual practices with the rhythms of the land. Many paintings depict lush valleys, flowing rivers, and Yellow River landscapes, emphasizing ecological awareness alongside cultural tradition. In these works, the spiritual, aesthetic, and ecological dimensions of life converge.

“Thangka is more than painting; it is education and a way to honor the river that sustains us,” the veteran painter told his students.

Niangben instructs students to create a piece of thangka painting. Photo: Courtesy of Niangben

Vitality from cultural integration

Today, Regong thangkas continue to innovate while remaining rooted in tradition.

“Contemporary thangkas must keep pace with modern aesthetics to ensure their continued transmission. Art must continuously innovate to attract young people, collectors, and museums,” said Niangben.

The Regong style has evolved over time, absorbing influences from Tibetan thangka and gongbi painting, a realist technique in traditional Chinese painting. Niangben himself studied gongbi skills in Chengdu, Southwest China’s Sichuan Province, under master Luo Jiakuan, copying more than 70 murals from the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644). This training allowed him to integrate meticulous linework with the soft colors and subtle shading of Regong thangka.

That style has been reflected in his and his apprentice’s works in recent years. For instance, The Great Unity of 56 Ethnic Groups is on display at the Cultural Palace of Nationalities in Beijing.

“From the initial sketches, every costume, gesture, and expression of each ethnic group was carefully arranged,” he told the Global Times. “We then layered mineral pigments, blended colors, and outlined details, until the work was complete. The finished piece is like a vivid photograph, showing the distinct styles of each group and their spirit of unity.”

In his fourth year in Tongren, Fan gradually shifted his focus from traditional thangka painting to the study and reproduction of ancient Chinese murals. He tirelessly studied the most famous temple murals from the Yuan and Ming dynasties (1279-1644) through books and online resources, experimenting with using traditional thangka techniques to create works that depart from conventional thangka styles.

Fan observes that today’s Regong thangka itself is a vivid testament to the fusion of various ethnic cultures. The landscapes he paints in his thangka works often echo the green-and-blue landscape style found in traditional Chinese painting. Under the influence of Central Plains culture, the subjects depicted in thangka art have also continued to expand beyond Buddhist stories. It can be seen that depictions in thangka paintings of historical figures such as Li Shimin, an emperor of the Tang Dynasty (618-907), architectural elements like traditional dougong brackets, and local wildlife such as snow leopards and Pallas’s cats. After the release of the animated blockbuster Ne Zha, Fan even used thangka techniques to paint the main character Ne Zha.

Another Regong thangka artist, Wande Jiancuo, told the Global Times that such innovation comes naturally. Nourished by the Yellow River, this golden valley of Regong is itself an integral part of Yellow River culture, so Regong art has inevitably been deeply influenced by the diverse ethnic cultures found along the river’s course.

As a national-level inheritor of the intangible cultural heritage, Niangben not only teaches his students the painting techniques of thangka, but also introduces them to the cultural roots of this intangible cultural heritage, which is as Wande describes, so as to foster a living cultural heritage.

“I teach them every step – mixing pigments, sketching, layering colors, and gilding,” he said. “It is through hard work and practice that students grow from simply being able to draw to creating true works of art.”

In every stroke, the influence of the Longwu River and the Yellow River basin can be seen: a convergence of land, culture, and faith, carried forward by hands dedicated to both craft and community.

“Regong thangka is our heritage,” Niangben said. “It is nourished by the Yellow River, and it will continue to thrive for generations to come.”