Ushering me quickly through Magdalene’s dark green dining hall, Simon Stoddart, the College’s ‘keeper of pictures’, pulls at a dull iron handle behind the high table, pulling back a wall panel to reveal a musky stone chamber. This is where the fellows gather to enter formal, he explains, before turning back towards the hall and throwing open the door, exclaiming: “Hall is theatre. Theatre is art.” After emailing Stoddart about my project on dining hall art, he insisted we speak in person and, given his effusive passion for this space, I understand why. Given that many like Stoddart take such pride in their dining halls and the figures that hang on them, I want to understand where this passion comes from, and how this theatre is directed.

Upon entering any college’s dining hall, I cannot help but take in the menagerie of faces which hang on its walls. Each student must sit eye-to-eye with their predecessors, sharing their meals with a stage-managed history of the college.

“Hall is theatre. Theatre is art.”

I enter Trinity Hall’s duck egg dining hall with Alexander Marr, the College’s picture steward. He tells me that dining hall art should at once represent “the history of the college” and “speak to current students, fellows, and staff,” and the way they perceive their institution. The first point on Marr’s to-do list, when he took the role in 2012, was to introduce female faces to an all-male collection. When showing his daughter (then four years old) around his new place of work, she stepped into the dining hall and exclaimed: “Daddy, where are all the mummies?”. It’s a memory that has stayed with him: “That’s one of the reasons it’s important to think about who is on the walls.” The first portrait of women in the hall has since been introduced, of the College’s first two female fellows, Dr Kareen Thorne and Dr Sandra Raban, but more are on the way, Marr says.

The position of female figures in these spaces is an uneasy one. Speaking to two friends at Caius and John’s, they report shockingly similar memories of when female masters’ portraits were mounted in their dining halls. The criticisms were apparently because these masters are still in post, and so breaking an unspoken tradition of fellows only being given a portrait after leaving the college, but are no doubt grounded in gender. “What’s this woman doing on the wall with all these old men?”, was apparently the sentiment among some at John’s.

The aura of the dining halls themselves is a testament to the insistence of many of the people I have spoken to that they represent not just an aesthetic representation of the college’s image, but are by-products of a college’s storied history and its key players. These portraits, then, appear to drip down from the ceilings in drops of red and gilded gold, a fact of life here, accumulating slowly like driftwood on the shore of the Cam.

But perhaps not all change is easily captured in a simile. Can we shift the status of dining hall portraits through our reception of them, even if the portraits themselves remain mounted? We shouldn’t have to, says Trinity Hall alum and artist Sophie Mei Birkin. “I don’t think the onus should be on the viewers to have to change. I think there should be an openness to thinking about what we put on the walls and what that communicates,” Birkin believes.

A 17th-century painting of a fowl market was thrown out of Hughes Hall because it was “putting vegans off their food,” reads a 2019 Daily Mail headline. The painting was returned to the Fitzwilliam to show “sensitivity” to students who found the work, ‘The Fowl Market’, to be “slightly repulsive”. That the Mail’s anti-woke crusade turned on those asking politely for a painting to be taken down proves that to simply unhang an artwork is seen as tantamount to dismantling the building brick by brick.

Discussing my project with friends, my suspicion is confirmed that art is seen as a permanent part of a dining halls’ walls, as fixed and unimpeachable as the wallpaper. To consider the art as something that could be moved around and commented on, as something that was once hung up rather than which just materialised, is seen as odd and rather futile. “There’s basically nothing there other than a huge picture of Henry VIII, and we were founded by Henry VII,” one friend remarks of her college, Jesus.

“I think there should be an openness to thinking about what we put on the walls and what that communicates”

Where art at Jesus is viewed as arbitrary, the selection process at my own college, Homerton, is seen to be totally at odds with its students’ wishes. There is a legend here that the principal was given the choice between building a swimming pool and buying a new painting, and he chose the painting. ‘A Florentine Procession’ is a grand, metres-long painting depicting dozens of lavishly-dressed worshipers marching from right to left. It now squats behind a thick red curtain in our rarely used old dining hall, which now hosts more silent disco bops than formal dinners.

And if students are ambivalent towards their dining hall art at Jesus, resentful at Homerton, then they are downright aggressive at Downing, at least according to rumour. The many paintings in the College’s grand red dining hall, so the story goes, were locked away from the hands and forks of drunken students who couldn’t resist flinging scraps of their dinner at the faces of their former masters.

At King’s, Nicky Zeeman, the College’s keeper of collections describes the collection of paintings she has introduced, mostly of members of the Bloomsbury group: “My two criteria,” in introducing this new collection to a space which had been dominated by traditional portraiture, “were paintings that are beautiful and have interest in themselves, but also paintings where the sitter is an interesting person, part of the history of the college or Cambridge more generally”. Suddenly, two large, wall-height paintings at either side of the display catch our eye, clearly out of place in this celebration of a recent intellectual history of King’s. “We still need to work out what to do with our really big 18th century guys,” Zeeman says, waving a mock-exasperated hand.

Later, she takes me to a smaller collection of portraits of current students and fellows of the College, a proud reminder of common sense prevailing over tradition: “Previously there was a rule that there couldn’t be any portraits in here that weren’t of former members, which by definition meant that they were all guys.” As I gesture towards another cluster of older portraits in the corner of the room, Zeeman nods. “In my view, these guys are all placeholders,” soon to be replaced by a full collection of contemporary pieces, she says.

“All paintings discolour and age. Nothing is eternal, nothing is fixed”

Zeeman’s awareness of portraits as static moments in time is refreshing. She admits of the collection of Bloomsbury paintings: “What this obviously doesn’t do is reflect King’s now we’re 100 years on.” But, this is an improvement on the hall’s previous iteration, she says, which “reflected a picture back at ourselves which stopped sometime in 1860”. “It’s a slow process,” she says, but one which is constantly in progress.

In Magdalene, Stoddart takes me through the newer additions to Magdalene’s hall, keen to emphasise that these are living spaces: “This is obviously a traditional college, but tradition needs to be reheated. Tradition develops. Tradition is not static, otherwise it dies.”

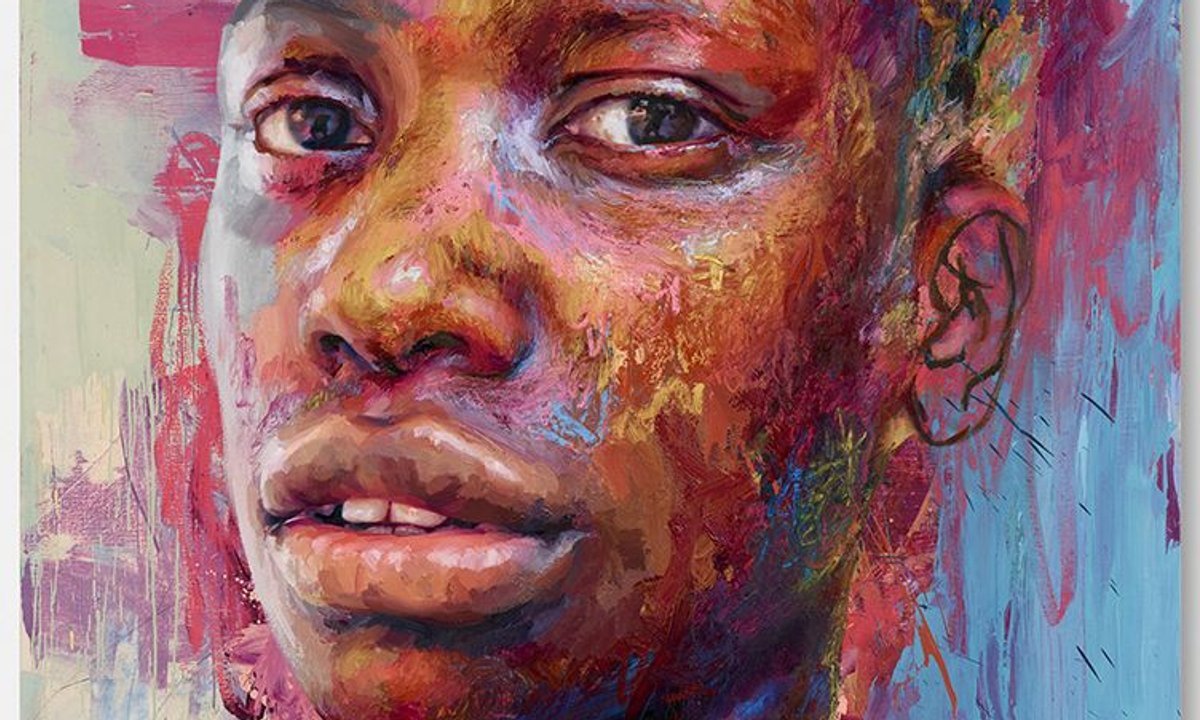

Similarly, Gonville and Caius’ art attempts to connect with its identity more meaningfully than just by putting frames around each of its past masters. A large portrait of Stephen Hawking, which noticeably celebrates rather than masks his disability, is centre stage, framed by stained glass above him on either side. These geometric shapes playfully balance between ecclesiastical tradition and the cutting edge research that Cambridge is known for.

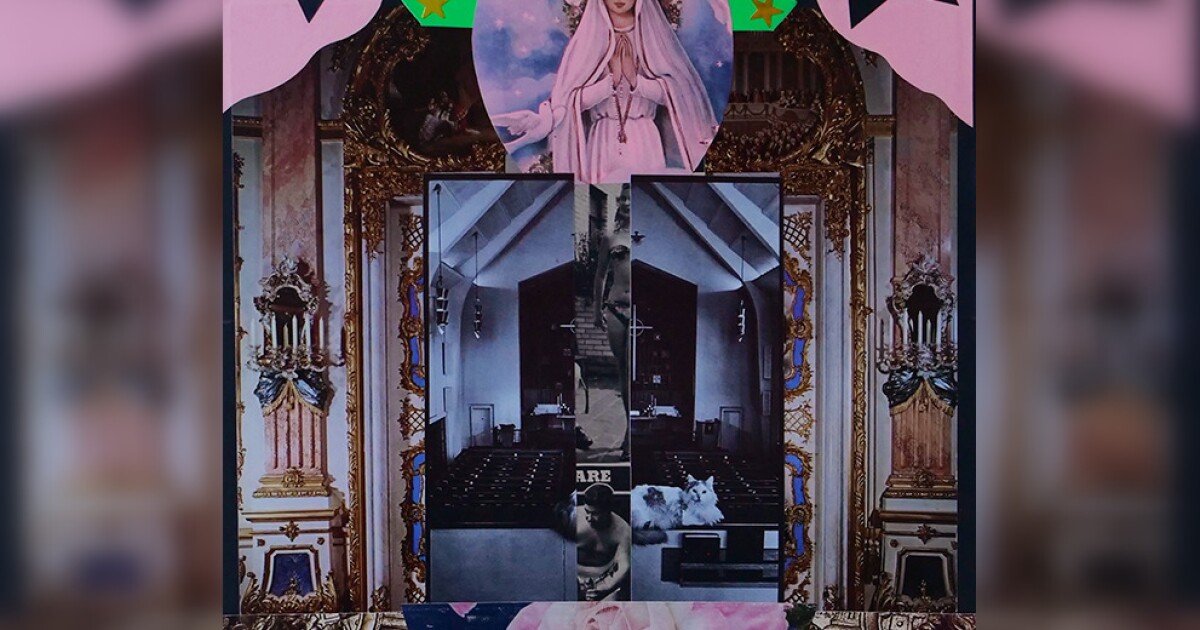

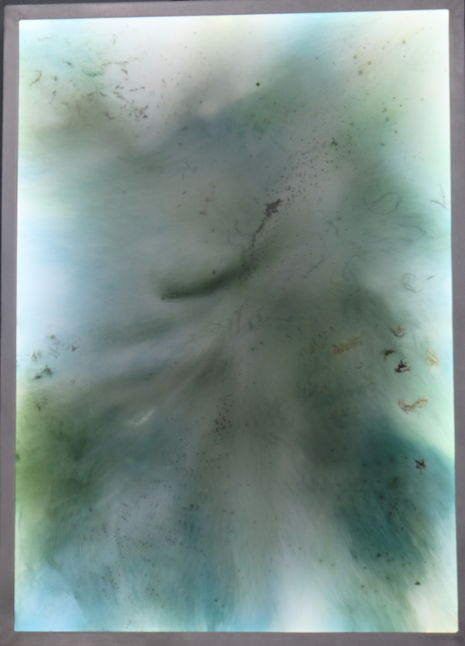

One of Marr’s introductions to Trinity Hall was Birkin’s ‘The Willow Will Submerge in Time’, an abstract piece made entirely from biological materials collected from the Cam. While “portraits are about human achievement,” Birkin says, she wanted to take a “radical” approach to reflect a cumulative, multifaceted image of Cambridge. Both Marr and Birkin tell me that the piece was in part inspired by Xu Zhi Mo’s ‘On Leaving Cambridge’, which presents the city as a “changeable” place. Though her own work is particularly likely to degrade over time due to its materials, Birkin emphasises that all paintings “discolour and age, nothing is eternal, nothing is fixed”.

But despite the efforts of art experts like Stoddart and Zeeman, some colleges are moving faster than others. In Corpus Christi, few traditional portraits still hang, as the walls are now filled with photographic portraits of dozens of its female staff and academics. Each of the picture keepers I met are intensely proud of their colleges’ traditions, but also intensely eager to add to their chronology. But waiting for tradition to wash away, they seem to acknowledge, can be a lot like watching paint dry.