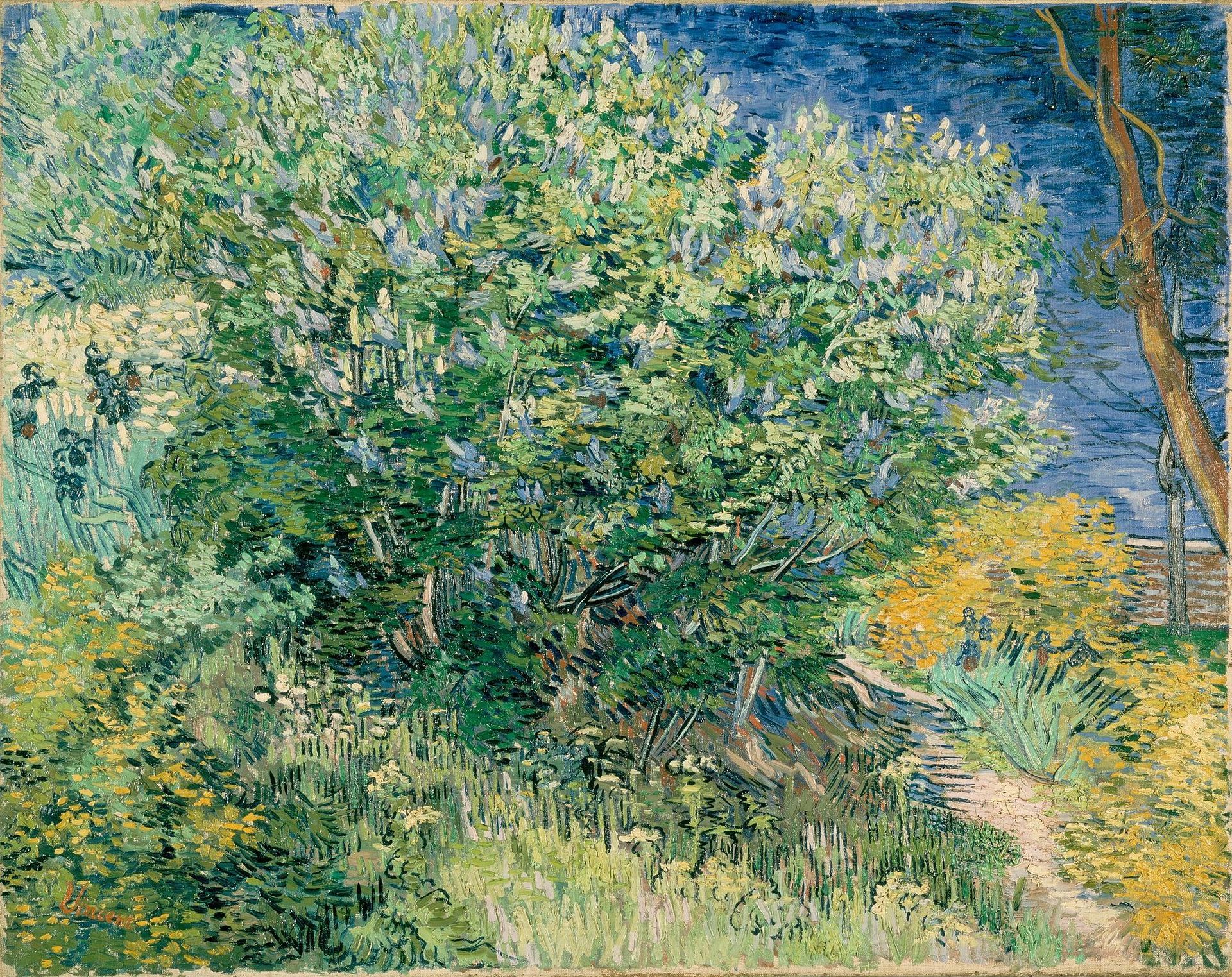

A fragment of pine pollen found within Van Gogh’s Irises has helped locate the place where the flowers flourished, at the back of the walled garden in the asylum where the artist stayed for a year. The painting, now at the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles, is among the artist’s most popular works.

Later this year the picture will be the focus of an exhibition at the Getty, Ultra-Violet: New Light on Van Gogh’s Irises (1 October-19 January 2025). In the meantime, we can reveal an important discovery.

Getty specialists have discovered a pollen cone embedded in Van Gogh’s thick impasto paint, in the lower left corner of the painting. Small male cones release their pollen into the air in early spring and a few end up fertilising female cones on neighbouring pines.

Enlarged detail of Van Gogh’s Irises, showing the pine pollen cone

J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

The pollen cone, measuring just over 1cm in length, is probably from an umbrella pine, an elegant Mediterranean tree which has long grown in the enclosed garden at Saint-Paul-de-Mausole, where Van Gogh lived for a year in 1889-90. Located just outside the town of Saint-Rémy-de-Provence, it is now a modern mental health hospital. Its walled garden survives relatively unchanged from the artist’s time.

The Getty specialists, conservator Devi Ormond and scientist Catherine Patterson, visited Saint-Paul in May 2022 and were allowed special access by the hospital’s medical director, Jean-Marc Boulon (who also runs an art therapy programme). He led them to a small mound at the back of the garden which he believes to be the spot where Irises had been painted—and where the flowers still grow.

On hearing about this, I was initially slightly sceptical that they were the exact type of iris which Van Gogh had seen, thinking that a similar variety might have been planted at some point in the 20th century in homage to the artist.

This spring I was also privileged to be taken into the garden, a private area of the hospital, and shown the mound by Boulon. This was on 29 April, but the flowers were already dead, whereas Van Gogh had painted them on 9 May, so I thought they might be an earlier flowering variety. With my limited botanical knowledge I wondered whether irises could flourish in the same place for nearly 150 years. And from the surviving traces of the shrivelled flowers, they appeared to be violet, not the blue of those in Van Gogh’s painting.

The iris mound at the back of the enclosed garden at Saint-Paul-de-Mausole, photographs taken in April 2023 and on 29 April 2024

Devi Ormond (2023) and Martin Bailey (2024)

But, on reflection, it now seems to me very likely that the surviving plants are indeed the descendants of those that Van Gogh had admired. Jill Whitehead, secretary of the British Iris Society, confirms that plants can live for very long periods in a garden and could well have survived from 1889. Global warming could account for the earlier flowering. As for the difference in colour, we’ll come to that later.

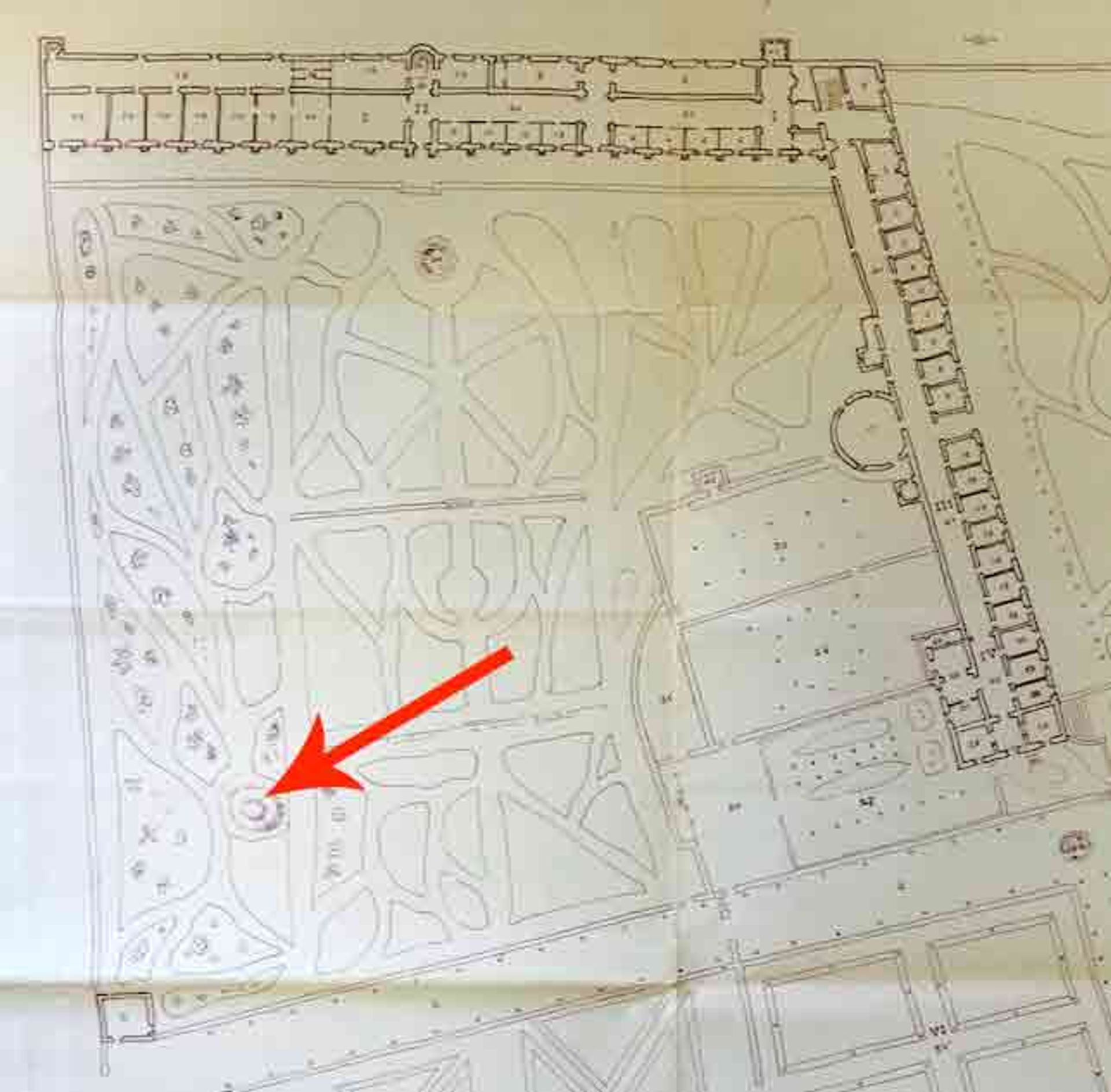

Plan of the walled garden and two medical wings at Saint-Paul-de-Mausole by Joseph Girard (1855), with mound indicated

Archives Municipales de Saint-Rémy-de-Provence

I was also able to identify the mound on an 1855 plan of the garden. Although the feature, which is a few metres high, could be man-made, it nevertheless existed in Van Gogh’s time.

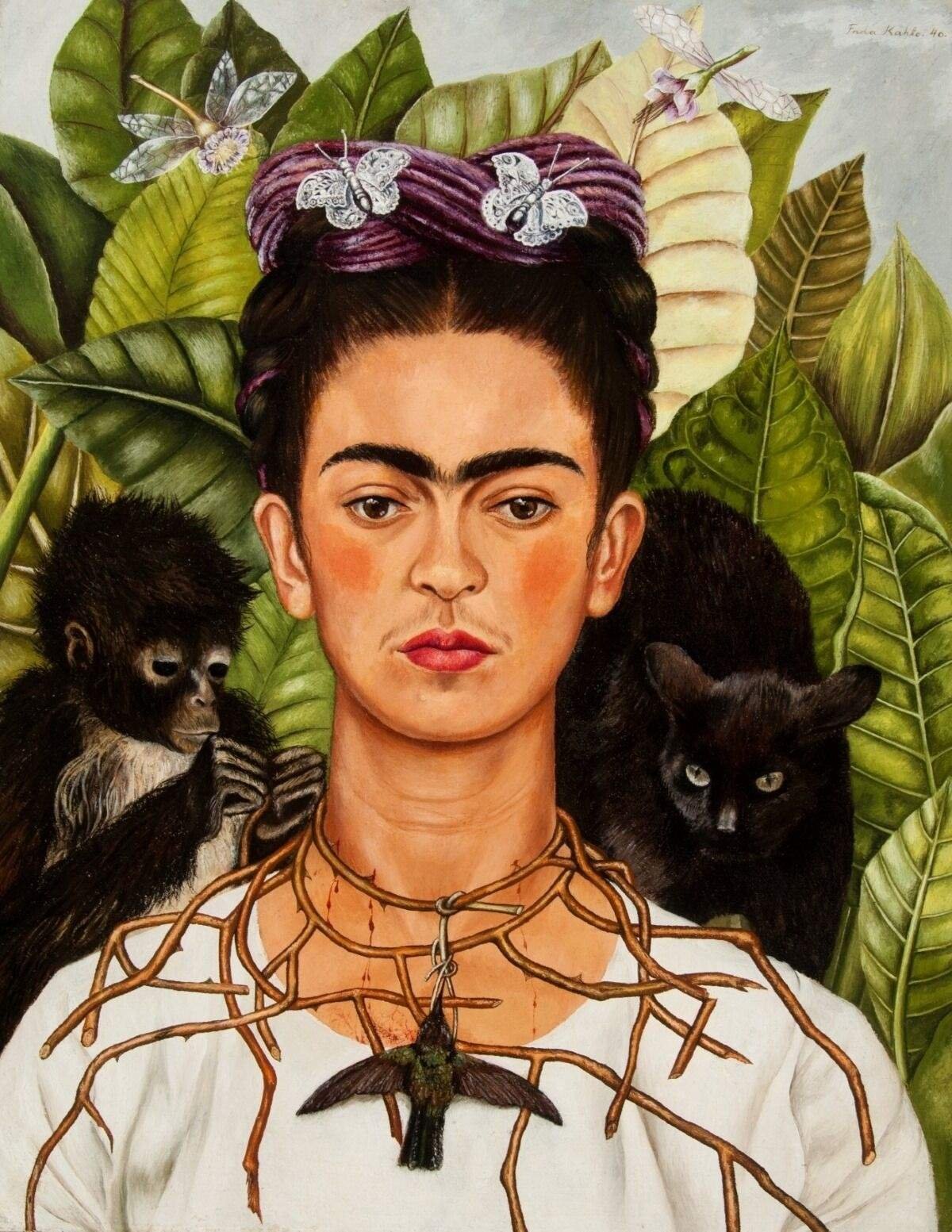

Van Gogh’s Lilac Bush (May 1889)

State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg

The mound appears in another painting by Van Gogh, Lilac Bush, on which he was working on the very same day as Irises. There are short rows of irises just to the left of the lilac and another next to the lower path. The trunk of a pine tree appears on the right, and this could have been the source of the pollen cone. In the background a short section of the stone wall is visible, helping to confirm it is the mound shown on the 1855 plan.

It is astonishing to consider the circumstances in which Van Gogh painted Irises. On 23 December 1888 he had suffered a mental incident and had mutilated his ear. For the following months he was in and out of the Arles hospital, in fluctuating health. Ultimately he accepted that he would find it difficult to lead an independent life and he decided to enter the asylum of Saint-Paul-de-Mausole, arriving on 8 May 1889.

The following morning he went into the asylum’s walled garden, equipped with his easel, canvas and paints. He probably headed towards the back of the garden (nearly 100m from the male wing) in order to seek privacy, and discovered the mound. His fellow inmates would likely have been very curious to see an artist at work and, had he worked closer to the building, they could well have been intrusive, looking over his shoulder.

The tall irises were then at their best. Van Gogh loved complementary colours, and he must have relished the sight of the blue irises surrounded by orangish yellow dandelions.

Having just moved in only a few hours earlier, Van Gogh presumably wanted to win the trust of the asylum’s director, Dr Théophile Peyron, who was allowing him to paint. The artist was therefore keen to make a success of his first picture. The doctor must have been astonished at the speedy and confident work of his latest arrival. Although many of Van Gogh’s paintings would have then appeared bafflingly avant-garde, Irises has a freshness and directness that the doctor may have been able to appreciate.

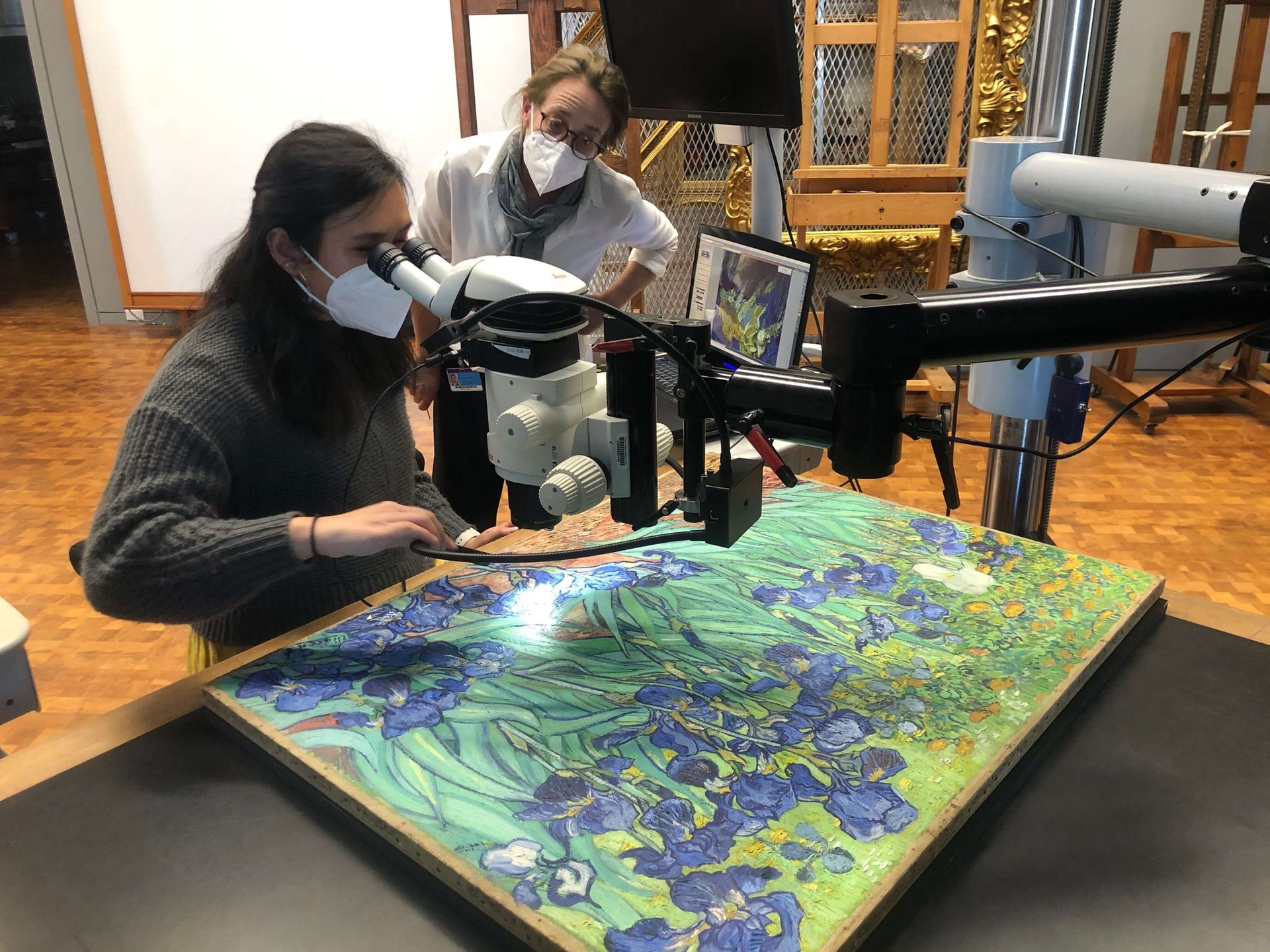

Getty paintings conservator Devi Ormond (standing) and Michelle Tengarra taking photomicrograph images of Irises

J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

The main investigations by the Getty specialists have involved examining colour changes in Irises using a variety of scientific techniques. In Vincent’s letter to his brother Theo of 9 May 1889 he describes the colour of the irises as “violet”. (This letter will be in the Getty exhibition, as an important loan from the Van Gogh Museum, which very rarely lends the artist’s correspondence, for conservation reasons.)

The original colour of Van Gogh’s irises is also confirmed by a review by the critic Félix Fénéon in September 1889. Referring to Irises, he wrote about the “violet patches” of the flowers, set beside their sword-like leaves.

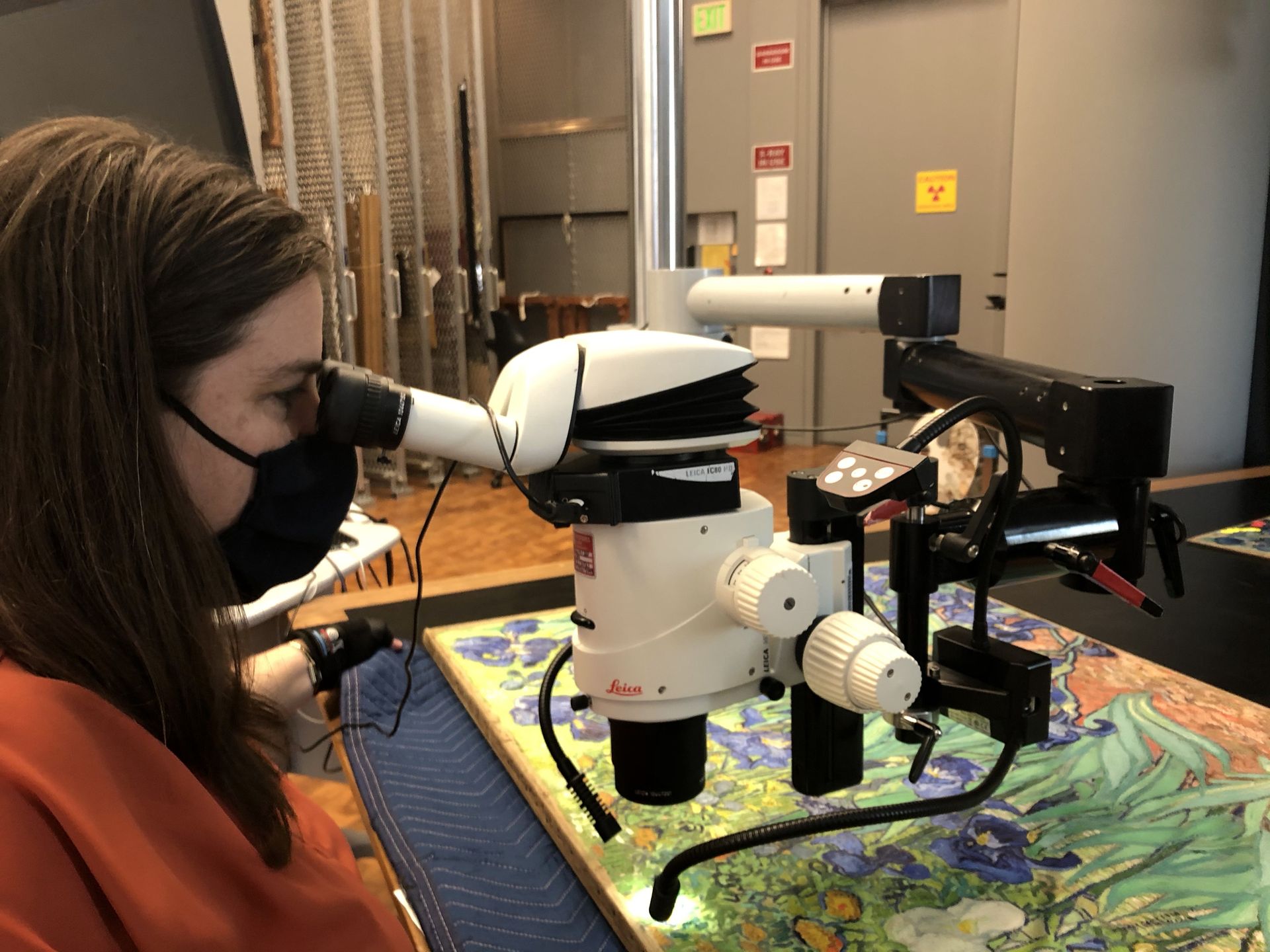

Getty scientist Catherine Patterson using a microscope to examine Irises

Getty Conservation Institute, Los Angeles

Ormond and Patterson now believe that Van Gogh’s red pigment (known as red lake) in the flowers has faded. This means that his original violet—a mixture of red and blue—has now become much closer to blue, or to be more precise, a range of blues.

At the opening of the Getty exhibition the museum will unveil a colour reconstruction of how Van Gogh’s painting may have originally looked. This image will appear even more vibrant than the picture in its present condition, with the violets reverberating against the small yellow centres of the irises and the neighbouring yellow dandelions.

Although Irises will remain at the Getty and not be coming to the National Gallery’s exhibition on the artist’s period in Provence, Van Gogh: Poets and Lovers (14 September-19 January 2025), several other paintings of the asylum garden will be on loan to the London show.