Hilma is a lush biopic about one of the first abstract painters in Western art history, a Swedish woman by the name of Hilma af Klint, who set off to challenge the entire artistic world in the late 1800s. Even though she easily mastered the more traditional avenues of illustration like portraiture and landscape paintings, Klint quickly found herself on a more spiritual plane, deciding to draw line-based symmetrical images that represented a depth beyond form.

This was all undoubtedly inspired by her family’s vested interest in the studies of numbers and plants, her circle of friends (called The Five who introduced her to the pseudo-religion of Theosophy), the underlying concept of the High Masters and eventually her idol, a mid-1900 famous architect named Rudolf Steiner who always wanted to find a connection between science and spirituality. Unfortunately, Klint came to the conclusion that the world was actually not ready for her deep-meaning artistic works and arranged for them to be hidden away for 20 years after her death.

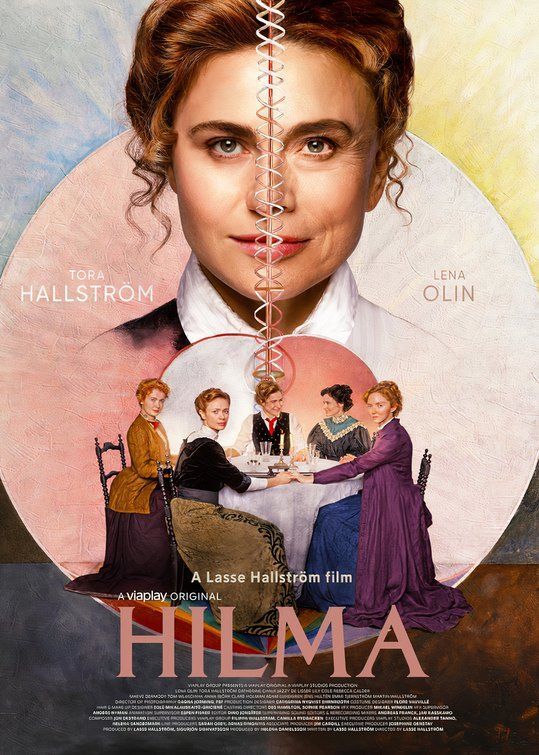

Hilma’s abstract paintings were finally released to the public in the mid-1980s during a Nordic Association for Art Historians conference in Finland. Now, three-time Academy Award-nominated director Lasse Hallström‘s biographical drama, Hilma, has been released on Viaplay (a streaming service specializing in the best of Nordic and European series and films), which is available for US customers on Prime Video and Roku devices. The film explores the life of this extremely groundbreaking artist and her struggles in a world that wasn’t ready for her art.

The Duality of Hilma, Abstract Artist

This biographical retelling stars Hallstrom’s wife (Lena Olin) and daughter (Tora Hallström) as an older and younger version of Hilma af Klint. While Olin has many more acting credits to her name than her daughter (for now), the two women both very much succeed in bringing different versions of the artist to the screen.

Even though there is a lot of tragedy and conflict to be found in the first part of Hilma’s life (such as when her younger sister suddenly passes), and some melodramatic mannerisms as a result, the young Hallström does well in balancing those moments with an equal amount of naivety in being a hopeful artist. Her sense of pleasure is extremely evocative when she’s painting, finding herself through love or spirituality, or connecting with her peers.

On the other hand, Olin shows an older and more tortured artist, one who carries the weight of a negative and neglectful world on her shoulders, hurting from all the ignorant insults and longing for a more welcoming past. Her Hilma is no longer surrounded by friends and colleagues but now talks to ghosts for company and pleads to others for some sort of guaranteed place for her works to be shown. Olin’s time in the film is shorter than her daughter’s, and the film would have benefited with more screen time from her. Hallström wife has a much stronger hold on conveying a sense of conflict to the audience.

Related

10 Movies About Painters That Are Visually Stunning

Movies about painters can be just as beautiful as their art.

Balancing Spiritual Context with Artistic Adventure

In order to please a general audience, it seems as though an explicit explanation behind Hilma’s main motivations (spiritualism, the High Masters, and general mysticism) is somewhat sidelined and replaced with a colorful and almost euphoric adventure. Whether different shades of blue and yellow suddenly whisk viewers away during a montage of Hilma painting or archival outdoor city shots are green-screened as a background to deliver a special out-of-time effect, there’s certainly enough here to entertain not only fans of the genre but art in general.

Mysticism is sporadically represented, however, as when Hilma thinks she sees her deceased sister in a glass of water (and the audience is supposed to genuinely believe it), or when she starts to coincidentally chant the same proverbs as one of her friends during a seance. It’s stylish and emotional but honestly confusing. These moments could have been replaced with more contextual dialogue explaining what exactly it is that these numerous women truly believe in.

Related

10 Movies About Experiencing Life as an Artist

These movies really get what it’s like to be inside the mind of an artist.

A Cleverly Queer Study of Hilma Stumbles Due to Rudolf Steiner

Even though factual recordings of Hilma af Klint (letters, diaries, rumors) never actually state that the artist was queer or a lesbian, the Viaplay exclusive movie does lean into this notion quite drastically, and it helps to give even more life to the main character. Her struggles not only come through the misunderstanding of her art but also show through her relationships and make for one very tense scene (even though it is a bit over the top, even for a drama). This overall arc not only shows another side to Hilma that viewers wouldn’t otherwise see but also helps the movie flow more naturally to its conclusion.

Director and writer Hallström surely knows how to mischievously transform loving partners into ever-growing problems. British actresses Catherine Clark and Jazzy De Lisser, who eventually become Hilma’s significant others at different times in the movie, give opposing performances. While Clark’s character Anna slowly comes to a boiling point with her frustrations (and Clark does a great job of getting there), Lisser’s character of Thomasine is too subtle to even be noticed at times. The question quickly arises if Thomasine was created solely to become an opposite to Anna in terms of holding Hilma’s attention. Not that it matters much in the actual conclusion, but the payoff to the love triangle is memorable for only one of the parties involved. The other just fades away into the background.

Another rising tension is seen in Hilma’s encounters with the aforementioned Dr. Rudolf Steiner, who was involved in Ms. Klint’s actual life and dismissed her works at numerous points too. In a movie where one of the more prevalent themes revolves around men holding onto their place in society at the detriment of women, why does Hilma instinctively regard this man as her soulmate (multiple times) even before meeting him? The pursuit of this man now turns into an awkward and almost cringe venture. She’s already defying societal norms by publicly showing that a female is interested in intellectual, abstract art, but the script manages to erase the strong, independent message when it comes to Steiner, who was essentially a cult leader.

Hilma Ends Strong and Her Art Lives On

Fortunately, the film comes together at the end and pushes past its flaws as Hilma makes an inspirational final statement to close the film. Just as the two-hour movie begins with Olin’s rendition, the film ends with her desperate portrayal of Hilma as well. The older actress takes a simple bus ride and turns it into a very intimate, selfless performance. After requesting a 20-year wait to unveil her art (because she feels as though the world is not ready to appreciate her pieces), a time-skip for a conclusion does ultimately satisfy those who kept wondering if our main protagonist would come out of her struggles with the legacy that she so desperately wanted and deserved.

The world has changed for the better in many ways, and people are looking at her interpretive artistic installations with a different kind of eye. While not as strong as his previous films, such as My Life as a Dog (1985) or The Cider HouseRules (1999), Hilma’s eventually liberating journey into a determined artist’s soul will leave you wanting to know more about the Swedish mystic.

After last year’s limited US theatrical release and success on the international film festival circuit, Hilma is now available to stream on Viaplay. You can watch it through the link below: