The British artist Jenny Saville has been exploring, stretching and reinvigorating the possibilities of representing the human form for more than three decades. While still in her early 20s and soon after her sellout 1992 degree show at the Glasgow School of Art, Saville’s monumental paintings of the naked female form were commissioned and bought by the collector Charles Saatchi, who exhibited her work at his eponymous gallery in 1994. Saville was also a conspicuous inclusion in the landmark Sensation: Young British Artists from the Saatchi Collection show at the Royal Academy of Arts three years later, even though her deep connections with art history and its traditions set her apart from her YBA contemporaries.

Since then, Saville has received much market acclaim, including breaking the auction record for a living female artist in 2018 when her self-portrait Propped (1992) sold for £9.5m (with fees) at Sotheby’s in London. But institutional recognition—especially in the UK—has been more elusive. The Tate has only one of her works, a painting titled Trace (1993-94), which is on long-term loan from her gallerist Larry Gagosian. But this is set to be rectified with a major survey at the National Portrait Gallery in London. The Anatomy of Painting, which opened in June, traces Saville’s practice from the 1990s to the present day.

Saville says the low-to-high perspective of Propped (1992) gives “a sense of awe, drama and powerful presence”

© The artist; all rights reserved, DACS 2025; courtesy of Gagosian

The Art Newspaper: Your new show is in the National Portrait Gallery, but your paintings and drawings of heads and the figures go beyond a traditional portrayal and engage in complex, multilayered conversations about how figure painting can be rebooted for the 21st century.

Jenny Saville: It’s not that they’re not portraits, it’s just that sometimes I push portraiture in lots of different ways. I think some people will see them as very traditional portraits with some departures that push at the boundaries of portraiture, or that will make you think about portraiture differently, or maybe that turns you back onto portraiture. I think it will just depend on the viewer. [The curator and I] have definitely chosen more portrait heads but there are also figures to make a representation of what I’ve done all these years: I’m excited to see the way my work has evolved and developed and how I’ve gone from wanting to build form to explore painterliness more.

Early works, such as Propped, which you made for your 1992 degree show, or Plan (1993), which was commissioned by Charles Saatchi, emphasised female flesh and form rather than faces. What was the thinking behind this desire to make work about the body, about corporeality?

I think that’s always been the same for me throughout. There’s such a strong thread through all my work: if you see the whole trajectory of what I’ve done, I think that from the early days of my graduation show onwards it’s been approaching the depiction of a body in lots of different ways over time. Early on, I had more of a relationship with the traditions of British realism. In my colour sense and picture making, that [Lucian] Freud, [Francis] Bacon and [Frank] Auerbach grouping were the big influences for me, as well as my interest in Old Masters that was also already there. Glasgow School of Art had a strong figurative tradition, it still had painting and drawing departments—whereas a lot of the English art schools had switched to fine art by that time—and that suited me very well. Also, just before I went to Glasgow, I’d seen the Lucian Freud painting exhibition at the Hayward Gallery [in 1988], which had a huge impact on my work.

These striking early works were emphatically female bodies—powerful but also in precarious poses. In the case of Plan, the body is marked up for cosmetic surgery, while Propped has text by the feminist theorist Luce Irigaray written in the background. Did you see yourself re-presenting the female form through the prism of feminism?

It’s very hard now to go back and remember what my exact thinking at the time was. But there was a moment when I was developing my painting when I had that theory swirling around. And at my degree show this combined with the paintings I was making.

Saville is sanguine about her record-breaking success. “It doesn’t make you make a better painting,” she says

Photograph: A. Saville

Your children were born in 2007 and 2008. What was the impact of childbirth and motherhood on your work?

Making art is a sort of diary, and so my work just naturally developed into looking at that subject. It’s incredibly beautiful and powerful and poignant and just a wonderful part of our human story. A whole range of depictions of the mother and child throughout human history—from Christianity to fertility goddesses—became pertinent, and I started looking at those and then the work started to emerge. I particularly wanted to get pregnancy and the rapid movement of children’s bodies into pictorial form, so I looked at Renaissance drawings of the Madonna and child, as well as Rembrandt’s pen-and-ink drawings of mothers and children.

Your enduring relationship with art history is well known and remains intense and vivid. Why is it so important to keep this conversation current and alive?

I think for all contemporary painters who look at Old Masters, the Old Masters are contemporary to them. You only have to go and see the Titian room at the National Gallery, it’s just sensational. They come alive in every era, and they mean something different to each era of painters that are around at that time. So they’re always relevant, they’re just part of the dialogue you have with other people in painting.

Another constant in your work, right from the beginning, is its very large scale. I remember when I first saw Propped in the Saatchi Gallery, it seemed epic.

It’s just a natural way for me to work. I’ve always liked to work on a large scale. I also like creating paintings of bodies and heads from a low-to-high perspective, which gives a sense of awe, drama and powerful presence, and makes things feel bigger. I’ve always had an eye for that kind of composition. When I made Shift and Fulcrum, and all the works for my first New York show [at Gagosian gallery in 1999], I wanted to get that grandeur. It was ambitious.

This large scale, and especially in the impasto surfaces of your more recent works, also brings the viewer into a close relationship with the materiality of paint. While your work is anchored in figuration, it also has strong abstract elements.

I think that’s where the tension in my work is. I like working on a large scale, and to make figurative art on this scale the paint becomes more abstract. But if you’re building a figure or a head you still have a rational process of how you build out that form, and that’s very much part of the way that I work: I like to have an image to get hold of. Yet at the same time the paint becomes more abstract, and it’s a challenge to get a level of realism at this scale. When you get up close, you are having a conversation with the paint, as well as with the sitter and I find that exciting—you get the sensuous joy of the paint and the person who’s modelled for the painting at the same time. There’s a positivity about life that I hope comes off the paint. I like to live in the present when I’m painting.

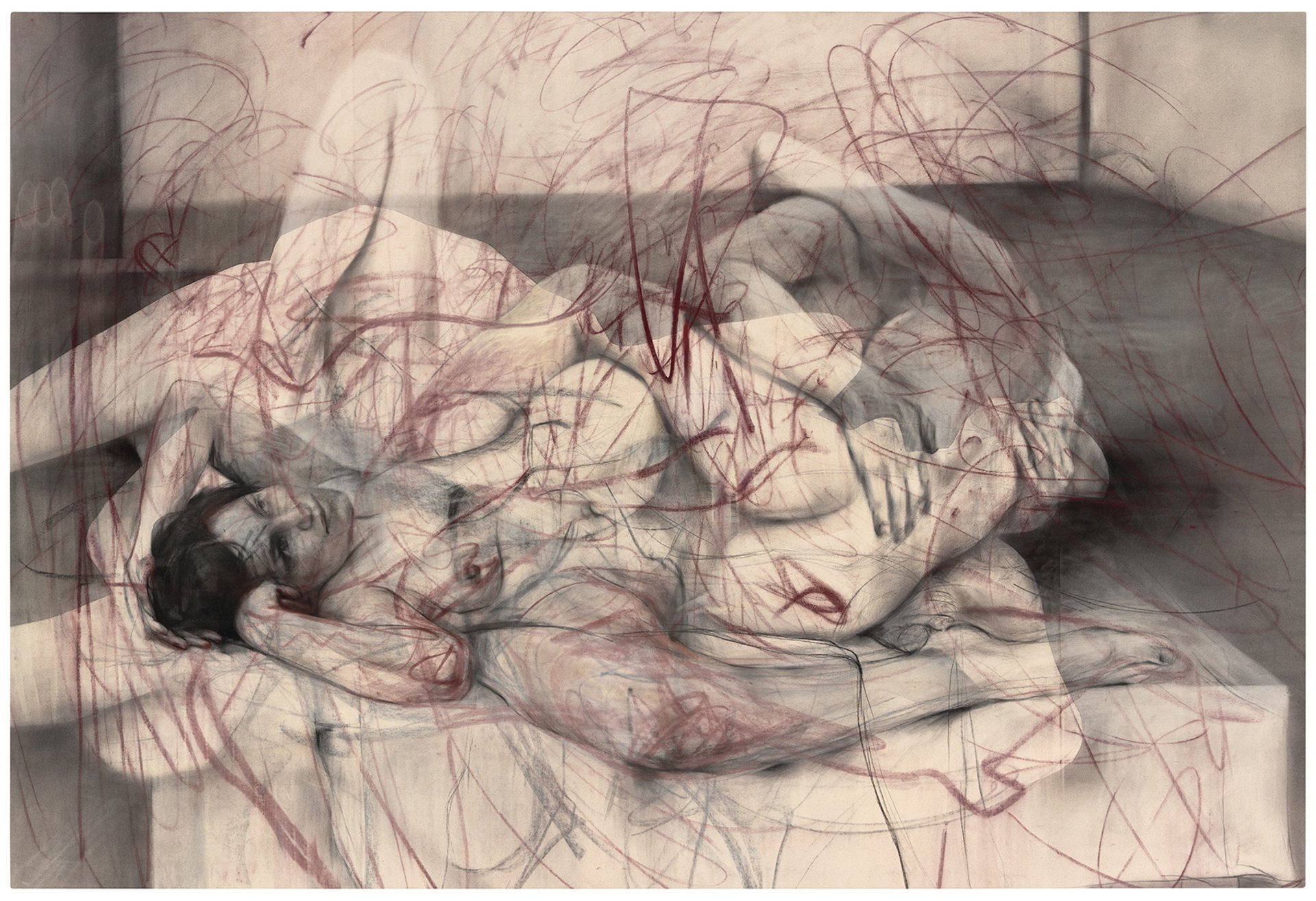

Jenny Saville’s One out of two (symposium) from 2016. Though best known for her paintings, the artist also has a love of drawing. “A drawing can traverse time in a way that paintings can’t do in the same way,” she says

© Jenny Saville; all rights reserved, DACS 2025; courtesy of Gagosian

Although it is called The Anatomy of Painting, the National Portrait Gallery exhibition also contains a number of large drawings in charcoal and pastel. How do you decide to make a drawing over a painting?

They evolve organically, it’s more of a playful thing rather than me saying, “OK this is the start of a project”. Drawing is intrinsic to me. I like looking at all artist’s drawings. It could be a [Gerhard] Richter drawing, it could be a [Jean-Michel] Basquiat drawing, it could be a Leonardo drawing or an [Albrecht] Dürer. I like all types. Drawings don’t have the veils of history in the same way a painting has. A drawing can traverse time in a way that paintings can’t do in the same way—they are so fixed in the moment that they were made. I like working in charcoal because of the different sizes of charcoal you can work with. I like that you can just layer-up one body on top of another, or you can create a depth through, and not just around, a piece. It’s an exciting way to work. Drawing, painting—it all intermingles. I like to experiment and to move between those things.

And yet, your first and lasting love is paint, and oil paint in particular?

Nothing has the density of colour of oil paint. I’ve tried using acrylic, but I find it more frustrating. Oil paint has a depth of pigment quality that I can’t find in other more modern media. I’ve made groupings of works in charcoal and pastel, but my language is oil painting.

I’ve looked at the pastels of artists like [Edgar] Degas and [Willem] de Kooning, and I found their ways to build form very exciting—but that’s gone back into my oil paintings. For me, painting is like a philosophy: the fact that it doesn’t do another job in society, other than be what it is, gives it a possibility to be something very important. I find the relationship of this very unique surface with our unique natures as human beings incredibly powerful. That painting has this very unique quality, that it can communicate something about reality, but at the same time be removed slightly from our everyday life, this is what keeps me so interested in it. I’m a painterly painter. I still find it a powerful way to work and that’s just the way that I’ve always been.

Right from the start you have enjoyed market success and your work has broken auction records. But you seem to prefer to keep a low profile, out of the commercial spotlight.

I don’t really have anything to say about the art market. The only thing I know deeply is it doesn’t make you make a better painting or a worse painting. You just have to make the best painting; the painting needs to be a certain way. And that’s just what I’ve done.

• Jenny Saville: the Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery, London, until 7 September

Biography

Born: 1970 Cambridge, England

Lives and works: Oxford

Education: 1992 BA Glasgow School of Art

Key Shows: 2005 Museo d’Arte Contemporanea Rome; 2015 Ashmolean Museum, Oxford; 2018 Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh; 2021 Museo Novecento, Museo degli Innocenti and Museo di Casa Buonarroti, Florence

Represented by: Gagosian