What’s the deal with Leonardo’s harpsichord-viola? Why were Impressionists obsessed with the color purple? Art Bites brings you a surprising fact, lesser-known anecdote, or curious event from art history. These delightful nuggets shed light on the lives of famed artists and decode their practices, while adding new layers of intrigue to celebrated masterpieces.

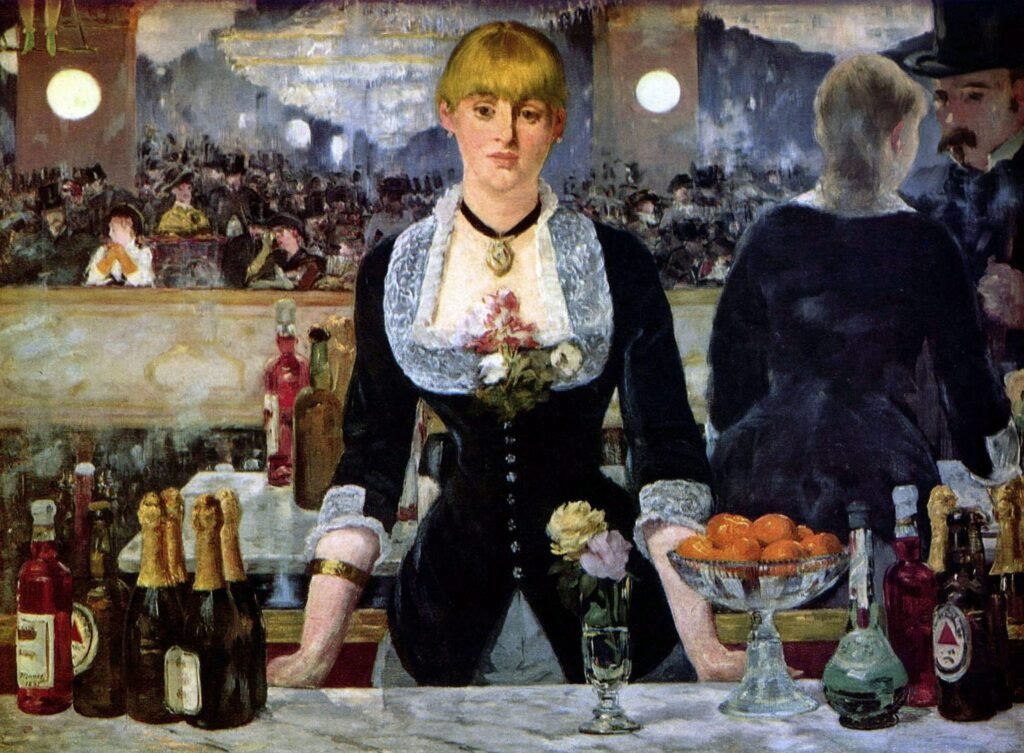

Nowadays when we talk about product placement, the conversation often revolves around the latest TV shows and Hollywood blockbusters. During the late 19th and early 20th century, however, paintings occasionally referenced consumer products also. Take, for example, Édouard Manet’s 1882 A Bar at the Folies-Bergère, which prominently displays the bottles – and logo – of a well-known British beer brand: Bass Brewery.

Completed a year before the French painter’s passing, A Bar at the Folies-Bergère was first revealed at the French Academy of Fine Arts’ annual Salon exhibit. Its setting is the the Parisian cabaret club that counted Manet amongst its many regulars. The packed venue is reflected in a large mirror that frames a barmaid standing behind a counter stocked with wine, champagne, liqueur, and—most notably—beer bottles from Bass Brewery. The company, identifiable by its crimson, triangular label, registered a trademark in 1876 to do so.

Manet wasn’t the only artist to feature real-world products in his paintings. On the contrary, commenting on consumerism was a defining feature of the artistic current to which he belonged. As art historian Ruth Iskin notes in her book Modern Women and Parisian Culture in Impressionist Painting, Claude Monet’s portraits of Parisian women double as recordings of Parisian fashion trends, paying close attention to pattern, texture, and material.

The iconic Bass sign with its recognizable red triangle logo appears on a billboard. Photo: George Rose/Getty Images.

Edgar Degas was similarly interested in consumerist culture, as demonstrated by a series of paintings of French millinery shops. When painting these shops, which sell and manufacture hats, Degas made sure to depict “the new display strategies developed by department stores to attract customers,” in Iskin’s words. Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec blurred the lines between art and advertising even further, designing posters for the famous cabaret club Moulin Rouge.

Manet did not paint Bass beer because the brewery was paying him to do so, but because he wanted to make a statement about the environment in which they were bought and consumed. Observant viewers will notice the painter put his signature on one of the bottles, critiquing not just the consumerism of Parisian nightlife, but the commercialization of the art world itself.

The bottles – which do not align with their reflection, mimicking the gaze of a drunk person – also connect to the painting’s hidden meaning. Writing for the BBC, art critic Kelly Grovier points out that the Bass label directs the eye towards the similar-looking flower arrangement on the barmaid’s bosom. Such arrangements were typically worn by sex workers, which many of the bar maids working at the Folies-Bergère were.

This, in turn, raises questions about the top-hatted customer the barmaid is talking to. Does he want to buy a Bass, or something else? Manet leaves it up to the viewer to decide.

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to get the breaking news, eye-opening interviews, and incisive critical takes that drive the conversation forward.