Jon Gower

Encountering Harry Holland in his studio in Pontcanna in Cardiff is to meet a self-effacing man. ‘I’m a workman,’ he says of himself, as if shy of using the word artist.

Someone widely considered to be one of Britain’s finest figurative artists openly tells you about the gifts he does not have:

‘What I haven’t got is that particular facility to make a mark in itself interesting. Kyffin Williams had it and Augustus John – one of my great heroes – he had it. The more I got to see of Augustus’ work, the more I understood how you can marry form with liveliness and line for example, and the depiction of character – Augustus John had it in spades. I think he’s one of the great draughtsmen ever.’

Harry Holland believes in the uniqueness of the Western pictorial tradition:

‘The way it tries to marry just about every aspect of human endeavour – science, love, history, sex – and bring them within it. For 400 years it’s been our way of looking at the world. I’ve often thought it remarkable that when photography was invented it was done to augment and facilitate drawing but it’s amazing how photographs looked exactly like Western artists had been trying to do for a quite a long time – reveal form by light. That’s the essential, the core of it.

‘It started with the Greeks. They believed that an absolute depiction of the world as it is was the highest you could achieve in art. They had an idea of beauty and they attached this idea of mimesis, the idea that some things are beautiful, so they would move towards an ideal.

‘Their sculptures are a good example, where you would take a human form – the figure, face and so on – and move it toward an ideal state that everybody should aspire to. But of course nobody actually conforms to that.’

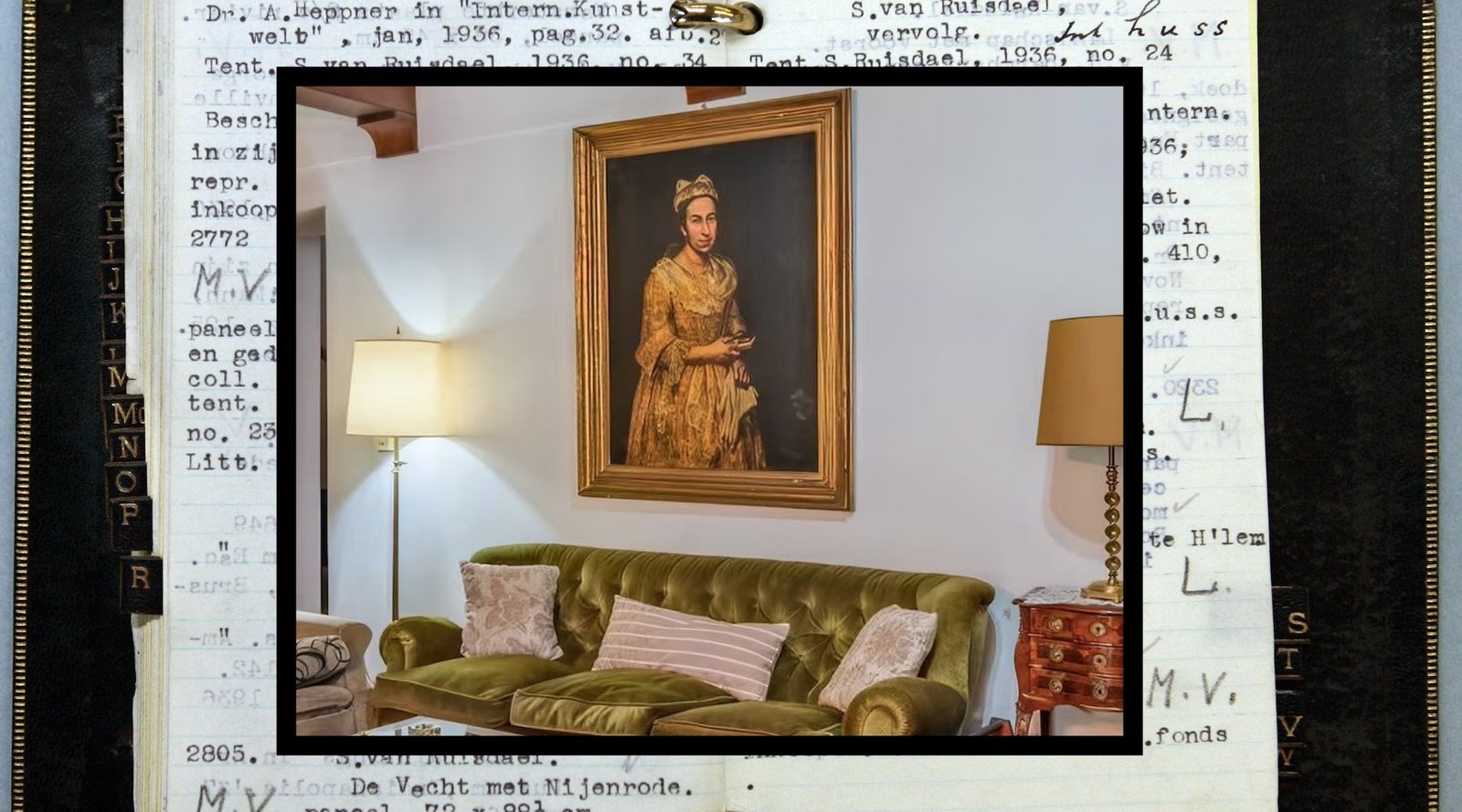

Holland’s usual subject, and that for which he is best known, is the human body and its shape.

It’s the main subject of a new book which contains many of his drawings of the body, along with some self-portraits and sketches of other subjects. But the human form is what usually engages him:

‘I think it’s so beautiful. Now beauty isn’t some sort of abstract thing – beauty doesn’t mean perfection, some sort of ideal state that you should aspire to. In looking at something it remind you of the fact that you’re a human being, alive in the world with other human beings and all the other things going on around you. That’s beauty as far as I’m concerned. And you can do that at its best with people.’

His first experience of life drawing was pivotal for him:

‘When I first went to art college at St Martin’s and started drawing academically I was so overwhelmed by the process that I’ve never really recovered – the life room was certainly one of the most important places, not only because of the model but also because of the teacher. It was a very human situation, a curious one really. There you are sitting or standing there looking at somebody with no clothes on, and all these other people are with you looking as well.

‘On the face of it, how bloody useless, it’s not going to get you any food or whatever but as a process it represents something that we all do all the time – we look at other people. One of my favourite places in the world is Cowbridge Road in Cardiff, looking at people there.’

Harry Holland’s paintings have a luminous quality, especially the lustre or sheen of the skin:

‘That’s one of the things I got directly from the Western tradition once I understood it – how to make things look real. One of the best ways is to echo the situation that you’re looking at. Human skin, no matter what colour is layered – muscle, blood, fat – and the skin, which is various colours goes over the top of that. In painting, especially Dutch painting you build up the form using layers and if you do that you get light, luminescent skin. It’s a very difficult thing to represent.

Harry Holland views some of the current art world with little joy:

‘Art nowadays has become currency, people are buying because it has a monetary value, an investment rather than because they like it. It happened in Holland in the 17th century. Holland became very rich and they developed a tulip industry. It was one of the first times when a market had been deliberately created.

‘And then someone applied this to art and started asking artists to do the same, mostly celebrating wealth. So those incredible still lives – with a pheasant and lemon and so on – only rich people could afford those. The market for Impressionism was similarly created by Russians, so you can see an awful lot of Impressionist paintings in St Petersburg.

Holland works hard and works every day. So what is the essence of his art?

‘The truth is I don’t know. I’ve tried to paint differently, paint different things, use different paints because I’ve thought this is getting a bit tired, all this stuff. They always ending uop looking like one of mine. I don’t really know why. I think it’s because in the end you look at the world in the same way as you’ve always done. If you start distorting your own view you really are in trouble I think.’

Art is a compulsion for Holland, taking him to the canvas and the studio as punctual as any shift worker. Drawing has always been a part of his life:

‘When I was a kid I used to draw. My mother painted all the time and did creative stuff such as crafts – making dolls – when I was growing up. My father was killed when I was two and my mother took up with a step-father: he wasn’t a bad man, he just wasn’t interested in anybody but my mother.

‘He was an itinerant chef and so I went to lots of different schools. It wasn’t until ten that I had a permanent place. The one thing I’d always liked, and was good at was drawing. Like many kids I loved comics Beano, Dandy, Hotspur and Eagle but I actually liked them because of the drawing and not the stories. Wonderful stuff.

‘Right about when I was twelve or thirteen an awful lot of American comics started coming into the UK, and a lot of horror comics. Lots of blues records at the same time, brought in by sailors, transatlantic trade.

‘Music started taking off at the same time and an awful lot of the illustrators of the 60s and 70s had been brought up on these imports. It was enlightening to see the speed with which the British took up these American cultural things, but they did.’

Art school came as a great opportunity, if a little later for Holland than for some:

‘After I got married a friend of mine who worked as a technician at St Martin’s College of Art said he could talk to someone about me to see if I could get a place there. My wife pointed out that there were grants for mature students from the Greater London Council and I was 23 at the time and I got in.

‘I finished art school in 1969 and one of my first jobs was as an illustrator, working on the Collins New World of Knowledge and I also did book covers, that sort of thing. Then I got a job as a teacher in Coventry. I started painting instead of illustrating because I could afford to spend time doing that. I learned more as a teacher than as a student.

‘When you start watching someone taking things in it reflects back on you. You ask have I got it and if so how did I get it and there is a whole load of technical questions you’ve never asked yourself until you had to explain it to somebody else.

‘In 1978 I gave up teaching because I was making money from painting by then. It was amazing – what you learn when you become a professional. You learn how to cut out an awful lot of the crap in the process.

Does he enjoy the response of people to his work?

‘There’s a myth in the art world that artists do things because they have it within themselves and all they’re doing is pleasing themselves. But any form of art is a means of communication and what’s the point in having that if you’re not going to use it to communicate something – the world as you see it?

‘But an awful lot of artists show the world as they think people want it to be seen and an awful lot of artists nowadays paint work which they think fits with the process that’s been created to make money, landscape art to sell to tourists and so on. They know it’s going to sell and good luck to them.

‘This idea that artists are hermetic – that there’s this garret somewhere – it’s rubbish. Artists are desperate for people to look at their work and what’s more the more people like it and the more people tell them why they like it the better because the artist often doesn’t know.

‘Pleasing somebody is important – you want to know that people are happy or they feel better or they look at something that they haven’t looked at before. It’s part of the love that you have of the world.’

Drawings by Harry Holland is published by Graffeg. It is available from all good bookshops.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an

independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by

the people of Wales.