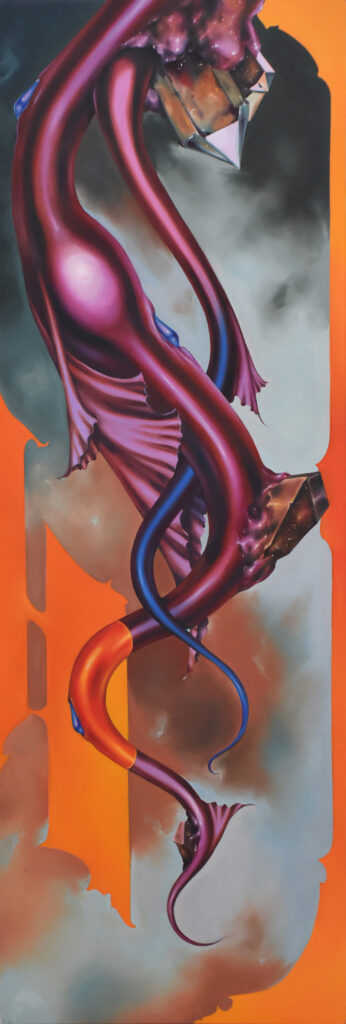

Ana V. Fleming’s oil paintings are a marvelous fusion of curious biomorphic imagery characterized by hyper-saturated hues that pulsate with intensity.

Her work unfolds within a dramatic, Baroque-inspired space, where mechanical and organic forms collide in sharp contrast. Her gliding, unearthly forms are executed convincingly, set against ethereal backgrounds that shimmer with a cosmic, electric charge.

The dynamic tension between the organic and synthetic, the natural and the otherworldly, is amplified by metallic surfaces that gleam with slick, luminous highlights, adding a surreal, value-rich depth to her paintings.

In her artist statement, Fleming reveals that her inspiration is drawn among “melding references from plants, marine biota, microscopic life, and imagined forms” as she visualizes “speculative ecologies that speak to the complexity and interdependence of existence on our planet and the preciousness of even those organisms most alien, most unfamiliar, most monstrous.”

After thoroughly exploring the artist’s work, Illinois Central College Dual-Credit Art Appreciation students from Tremont High School formulated questions for Fleming about her art and creative process — the following Q&A is a selection of the results of their collective inquiry into understanding Fleming’s work.

Q: You began your academic career as a writer; what inspired you to get your MFA in painting after receivng your B.A. in English from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign?

A: Growing up, I was especially interested in three branches of the arts: writing, music, and painting/drawing. I spent nearly all of my free time and available breaks in school developing my artwork independently (that is, without formal instruction, but rather guided by YouTube videos and visits to art museums and inspiration from friends and family). Since high school, expressing myself creatively — especially through visual art — was always something I had wanted to pursue and hone; however, I simply wasn’t confident enough in my abilities to pursue visual art as a formal degree in undergrad (and that was a self-imposed limitation).

So, instead, I studied engineering (for a bit) and then, eventually, English Literature. I deeply enjoyed my literature classes, and they ended up being invaluable as a foundation in critical theory, research, writing, history, and philosophy — all of which served me, crucially, at the graduate level. However, a part of me felt incomplete, and I had a kind of yearning to pursue the visual arts in earnest.

As such, at some point in undergrad, when, after rigorously researching my options, I discovered that graduate study in visual art was even a possibility (and that there were funded programs out there, to boot!), I instantly knew I wanted to apply. It ultimately took me two years (two rounds) of applications to get accepted into an MFA program. I ended up completing my MFA at the University of Notre Dame, and it was one of the best decisions I ever made; I’m so glad I finally gave myself the opportunity to focus on my visual artwork in a more dedicated capacity for three years. It made such a difference, and has continued to inform my artistic process to this day.

Q: Does writing feed your paintings or vice versa or both?

A: There’s absolutely a feedback loop there — so, yes, in both directions! I don’t really write as often as I should, but I find that reading and writing lead me to very different visualizations/mental images and outcomes than simply sketching, and oftentimes, as I’m working on drawings or paintings, the reverse will occur, and phrases, words, and sounds will emerge.

The mind is activated in different ways, obviously, when confronted by sounds, visual stimuli, smells, language — all of these specific forms of communication. Especially when I’m feeling stuck, it’s good to toggle back and forth between writing or painting, playing music, reading, etc., to refresh my creative baseline and, just generally, to expand my mind. Developing titles for artwork is always a great exercise in creative writing, and plumbing the depths of meaning possible within ideas expressed through language — even the meaning, the layers, contained within a single word.

I really love languages, and studying the etymologies of words, finding unexpected connections. Oftentimes, I go down a pretty deep rabbit hole when I’m deciding upon a particular word or title. Sometimes the titles end up becoming these microfictions in and of themselves, narrative complements to the image — and other times I’m just looking for that singular word that resonates, that captures an ambiguous mood, phenomenon, or reference point that links the image to other kinds of ideas and possibilities.

I find it extremely helpful to have a few different modes of creative expression available at any given time (writing, working with paint, working with charcoal, composing music, etc.) — the ideas can bounce back and forth like beams of light between all of these different mirrors, and as you angle the mirrors towards one another, they generate all sorts of unexpected pathways and inspiring patterns that you would have never otherwise encountered.

Q: In your artist statement, you describe being “fascinated by ecologies of the invisible” and “drawing from the literary genres of speculative and weird fiction.” Do you have any texts in particular that have been influential in your artworks?

A: Yes — many of them, and I credit a lot of my exposure to these texts to my undergraduate degree in literature. Herman Melville’s Moby Dick is actually one of my favorite books — it is an extremely unusual novel, in a lot of ways, but deeply philosophical and poetic. There are lines, phrases, and passages from Moby Dick that paint such a vivid picture in my mind, or that really challenge you to question your understanding of the world around you, and I have always found that to be extremely connected to my own interest in the parts of the world we can’t quite fully grasp, or that feel alien to us.

I was also pretty inspired by Jeff VanderMeer’s novel “Annihilation” of the Southern Reach trilogy, which I read in a “weird literature” course in college. I do read quite a lot of nonfiction, too — philosophy, books about nature, etc. Donna Haraway’s “Staying with the Trouble” was a highly influential text for me. I enjoy the writings of Michael Marder, a philosopher who writes a lot about plants and the ways that they are both fundamentally inaccessible to us, phenomenologically, but also what we might learn from them.

I’m currently reading a book by Helen Scales entitled The “Brilliant Abyss,” about the deep ocean. I try to read often — I always encounter new ideas that lead to lots of curiosity about the world, as well as visual inspiration.

Q: What inspires you to create mutations and nonhuman forms? How do you go from the ocean and plants to extraterrestrial beings and lifeforms?

A: I grew up very interested in animals and nature — my family always had lots of pets around, and my mom has a talent for cultivating a very abundant, active garden full of fascinating plants and bugs. I think just looking closely at animals, plants, insects, fungi, etc., really opened my eyes to how much depth and intricacy exists everywhere in the world around us, but can go so easily overlooked. In my art, I just hope to reflect some of that beauty, drama, and complexity and create a more conscious and reflective relationship to it. Obviously, there’s a lot in nature that is extremely horrifying, too — both existentially as well as visually or viscerally — and I am interested in trying to confront those aspects of reality, as well. I think where I make the leap to the extraterrestrial, sometimes, is trying to think speculatively and imaginatively about the deep past or the deep future — when humans are gone, but the complexity of life persists, just in new, difficult-to-understand ways. To me, that is a really intriguing philosophical and creative premise — what does it mean to contemplate a world that humans are no longer a part of? (Which is, in fact, most of the history of the universe .. since humans have only been around for an extremely brief period of time, cosmically-speaking.) That said, you really almost cannot create anything stranger than the things that already exist on our planet. Nothing I could imagine will ever be weirder than some of the plants and animals already out there, among us. So, it is just a playful exchange between trying to learn more about the weird ecosystems our world already has to offer, and then allowing myself to creatively improvise and respond to the parts of it that I feel most mesmerized by.

Q: What do you imagine while painting? Do you project these feelings onto your paintings?

A: I imagine a lot of things while painting, usually inspired by music I listen to while working, and by the films and creative content I have been exposed to most recently. I do actively visualize different color possibilities for any given painting as it develops — not always successfully, but it’s like solving a puzzle. You have to really spend time with it (the work of art) and remain open to different possible directions, even those you aren’t really sure you like. Color, especially, impacts how a piece feels so dramatically, so I try to consider how the colors are creating an emotional narrative or experience within each piece. And when I’m working without color, then I think a lot about light and shadow — I’m always pretty interested in high-drama images, whether that’s through the application of dramatic color or simply high contrast. Occasionally, I’ll work in silence, but a vast majority of the time, I listen to music that generates strong feelings and emotional reactions that can help me “feel” the tonal register of a particular piece — and I’m usually interested in at least some amount of tension within those feelings and moods. Painting is a very engrossing process in a lot of ways, but very emotional, I think. You are processing a lot of ambiguous emotion mentally and physically, too, and searching for a way to translate that ambiguity into a concrete, material form through color and line and shape and texture. It’s also a highly unpredictable/dynamic process, though, and so you are not 100% consciously aware of everything you are infusing into the piece (good, bad, or otherwise). I do spend a lot of time with my artwork at each stage — thinking about it while I’m sketching it out and developing the composition; thinking about it as I’m actually painting and adding layers; and then thinking about it once the image has been completed, but I still have to make a decision about the title, etc. Not every painting is successful, either, so those are feelings you also have to process — these feelings of failure, or frustration, or doubt. Typically, though, when that’s the case, it is a good sign that you are venturing somewhere new, and, in doing so, keeping your process fresh and open to growth.

Q: Do you start with sketches for your paintings — do you have an idea of what your painting would look like before starting, or is there a surprise impromptu with your work?

A: There’s a bit of both. I do absolutely begin with sketches — not incredibly detailed ones, but little thumbnails in pencil or pen on paper that give me a feel for the rhythm that I hope to establish in a piece. If I have a specific element in mind (e.g. a flower, a shell, etc.), I try to work out out how I want that element positioned, and then I experiment a bit with which other forms and elements will frame it. I also look at a lot of reference images and source material (photos of plants, bacteria, textures, color palettes, etc.) for inspiration, to help me find direction. Once I actually map out the contour drawing on my substrate — wood panel, paper, canvas, etc. — I usually continue to refine the drawing and add in little moments throughout. And then, once I start painting, things almost always begin to change, too — the paint often has a mind of its own. When you add color, everything takes on a whole new meaning. Some elements end up working, others don’t, so you have to remain adaptable and attentive to the painting at each stage of its development. I think that’s what keeps the process really fun and stimulating, though — you are always solving this puzzle that has no true “correct” answer, and multiple possible solutions. You’re just exploring this mystery until something aligns that “feels” right and speaks to you in this very embodied, sensory, or emotional way. I also take a relatively long time to finish pieces, too — it can take me weeks or, often, months to finish a single piece, so I’m really investing a lot of mental and physical time/energy into that image as it evolves, but I think my paintings need that. And, again, it also doesn’t always work out, at least not in a way you expect, which can leave you feeling ambivalent or conflicted about your work — but there’s beauty in that, too, because it entices you to continue searching.

Q: What are some current projects you are working on?

A: I’ve shifted to working largely on panel (as opposed to a stretched canvas substrate), and a body of work featuring shells. I am interested in shells in the way they simultaneously feel like bones, but are also connected to animals/living creatures, and yet they have this ancient, fossil-like quality, too.

The panel surface allows me to create really smooth, crisp detail, which I hope increases the sensitivity viewers will have toward the environments I create. I want people to be able to stare into these worlds and environments for a long time, to slow down, to linger, and to discover new moments the longer they look, even if the surface itself is small. I don’t know if it’s working, but I am enjoying even just the literal feel of the substrate and the increased sensitivity I have when I press my brush against the panel — you immediately respond to the right kind of surface.

I’m also experimenting a bit with wood staining and I’d like to venture into some more irregularly-shaped panels. I haven’t quite gotten there, but that’s an eventual goal. I have a few collaborative pieces I’m working on with fellow artists in the area, too, and that’s a really exciting challenge, responding to their work and finding inspiration in totally distinct, creative processes/approaches.

I’m always really inspired by the work of other artists, especially artists who achieve things that I don’t feel I could ever do! I’m really fortunate to have creative peers who I can interact with — near and far — some in central Illinois, and then others online whose work I can admire from a distance. I definitely want to give a shout-out to all of my artistic peers, friends, and family — all of whom offer their insight, feedback, and allow me to learn from them (in ways both small and big).

As my close friends and family know, I can often be extremely private about my artwork, but sharing my process with other artistic minds has been extremely rewarding and refreshing — even just cultivating that sense of camaraderie and shared creative experience.

Q: Is there anything additional you would like to share about your work?

A: I just feel extremely privileged to be able to paint and draw and create artwork at all. I’m further honored to be able to share that artwork with my community, online, and to have viewers respond to the work in a meaningful way. In some sense, as artists or creative individuals, you have no choice but to create — you are compelled to produce, to make, to solve that riddle, etc. — at least, somehow. But it’s also really a privilege to get to share your weird little creations with the world, or with your community, and I feel so humbled in every instance where people take the time to really look, to think about the artwork, and to ask questions about it. I have a long way to go, and, like every artist, my work is ever-evolving, shifting, morphing, and sometimes looping in circles. I also learn so much from other artists all the time — so anything I may have achieved in my own work, which might not be all that much just yet, is certainly indebted to all of the creative risks taken by others, both those who lived long before me, but also some of the really dazzlingly talented people within our own community. Even when it may appear extremely individual, most artwork is, in fact, highly collaborative. Thank you for such wonderful, thoughtful questions!

Go online to anavfleming.com