For the painter Julie Mehretu, whose works are currently on display at the Palazzo Grassi in Venice, a solo retrospective held little appeal. Instead, she chose to include other artists from a range of disciplines.

“Collective study is something I’ve been interested in for a long time,” she said by phone from Florence, Italy, “and not just with visual artists.”

The exhibit “Julie Mehretu. Ensemble” charts 25 years of her career and is the largest presentation of her work in Europe to date. But the works chosen are interwoven with sculptures, films, music and more by artist friends ranging from the 80-year-old David Hammons to her former partner, Jessica Rankin.

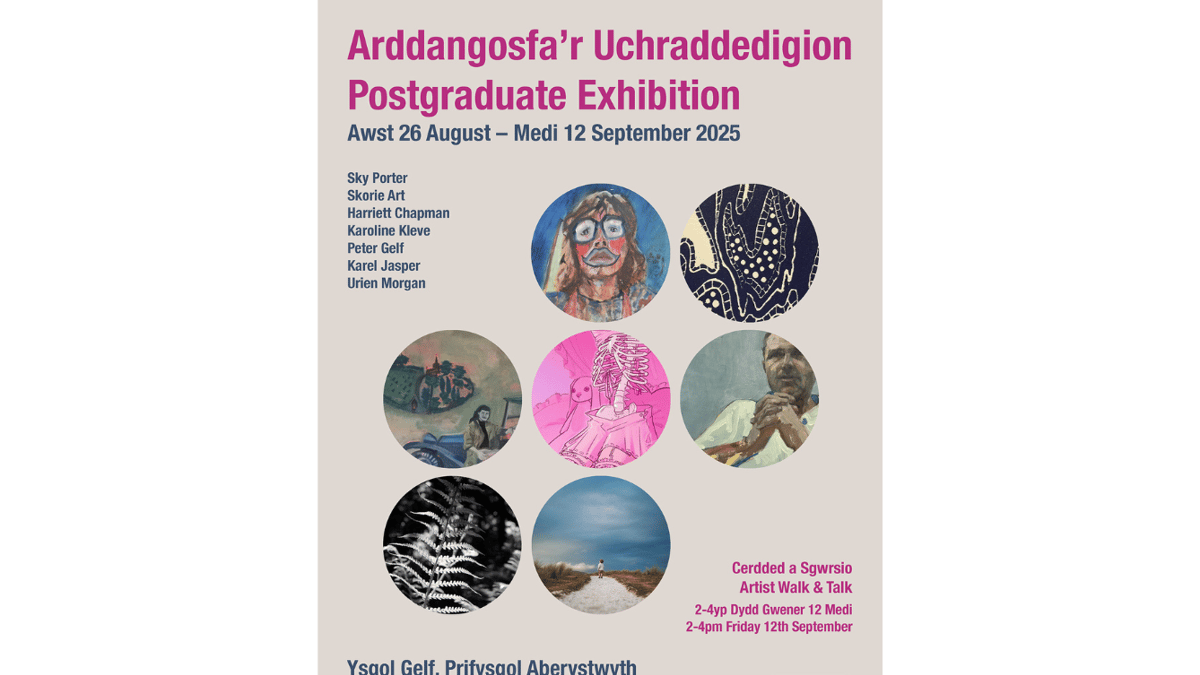

The show runs through Jan. 6 and will travel to the Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen (Art Collection of North Rhine-Westphalia) in Düsseldorf, Germany, next year.

Mehretu has established herself as one of today’s most original and thought-provoking painters with multidimensional canvases that take on global issues from war in Syria to the pandemic.

Ethiopian-born and currently living in Harlem, the 54-year-old artist has been recognized through such awards as the MacArthur “genius grant” in 2005, and was listed as one of the “100 most influential people” by Time magazine in 2020.

She has had recent solo shows at the Whitney Museum, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) and, last year, the White Cube in London.

But Mehretu also remains active with the sustainably oriented artists’ residency Denniston Hill in New York’s Catskill Mountains (which she co-founded in 2004) and was part of the experimental, multidisciplinary performance “Archive of Desire,” which traveled from National Sawdust in Brooklyn to the Palazzo Grassi last month.

Former collaborators also include the director Peter Sellars and the composer Jason Moran, whose piano composition “MASS {Howl, eon}” plays in the stairwell between floors of “Julie Mehretu. Ensemble.” The following interview has been edited and condensed.

Can we expect the current exhibit to recontextualize your work?

The interaction with the other artists offers a deeper way to consider it. There’s also a different sensibility to what happens over time.

This has to be experienced in person. Because what happens in front of a painting is maybe similar to the way you respond to music.

The curator, Caroline Bourgeois, knows this space and its rhythm intimately.

I learned a lot about the idea of expansion and contraction and what works in conversation.

The show features works from the recent series “TRANSpaintings,” which were presented in counterpoint with the sculptures of Nairy Baghramian in London last fall.

Two of these paintings are being presented for the first time. Nairy made sculptural frames that hold them, which were remade to fit the space in Venice.

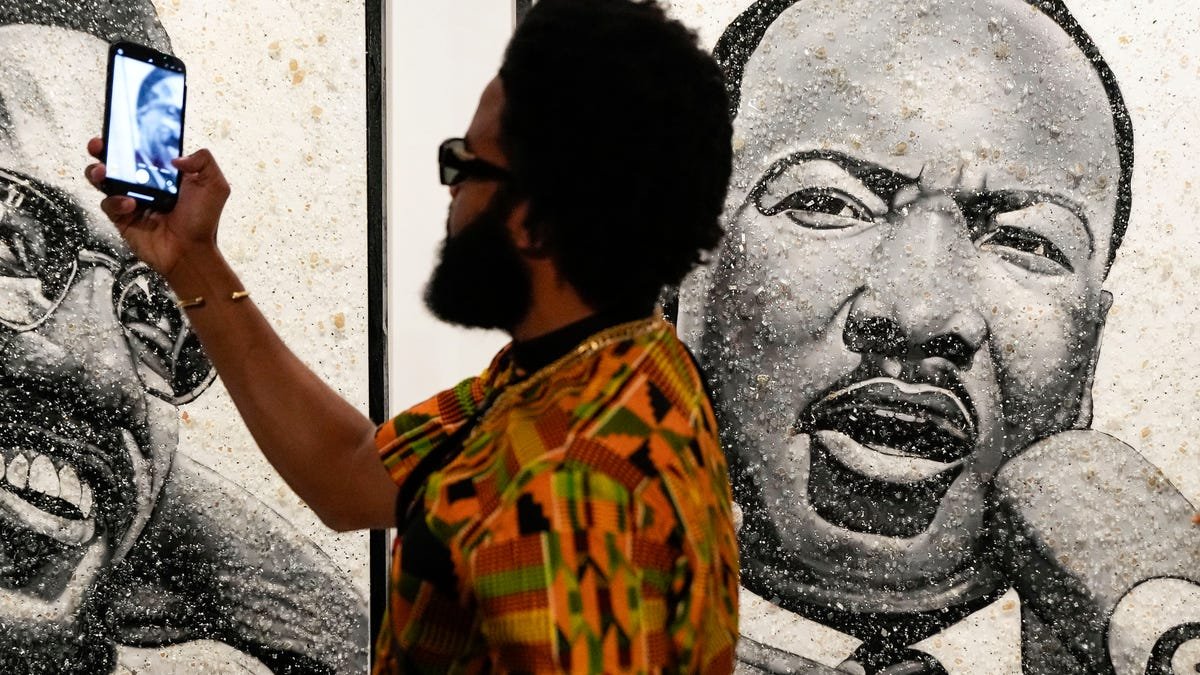

The paintings are translucent — light can come through and you can see shadows, or even a glimmer of the color of somebody’s sweater. So they really are affected by the audience.

And the frames participate in that. They fold, clamp and present the paintings — they feel like they could robotically start moving.

What else ties the various elements of the show together?

Most of the artists have immigrated by choice or had to move from their country of origin. So that, I think, is part of the connective tissue. But I’m more interested in something that has always been the case with artists: You never really experience a Duchamp show without seeing a Man Ray photograph because their work was made in conversation with one another.

My interest was in a group of friends who have had these conversations in very different forms for many years. Tacita Dean has made films with me. Jessica and I met in our early 20s; Paul Pfeiffer and I are very old friends (all three of us exhibited at the Project in Harlem).

I was interested in how we could push that as a dynamic. The question of what the connective tissue is doesn’t just get resolved but is something that we can think through as we experience the show.

You have written about confronting the breakdown of some of the promises made in the late 20th century and the way that our knowledge of the facts has become convoluted by forces such as social media. Does this make the need for serious art and a collective space of exploration more pressing?

We’re all negotiating the disintegration of many of the promises of modernity. We’re seeing it every day in the news. And we’re seeing it play out in real time in a way that I don’t think we have ever experienced as a collective people before.

In addition, most of us are not consuming the same information because every person has an individuated form of media on their phone.

The catastrophic realities that we’re facing in terms of the climate, in terms of our planet, in terms of humanity — we’re being tasked with the question of: How do we rethink this? And aesthetics and art and culture are one way of interrogating all of that.