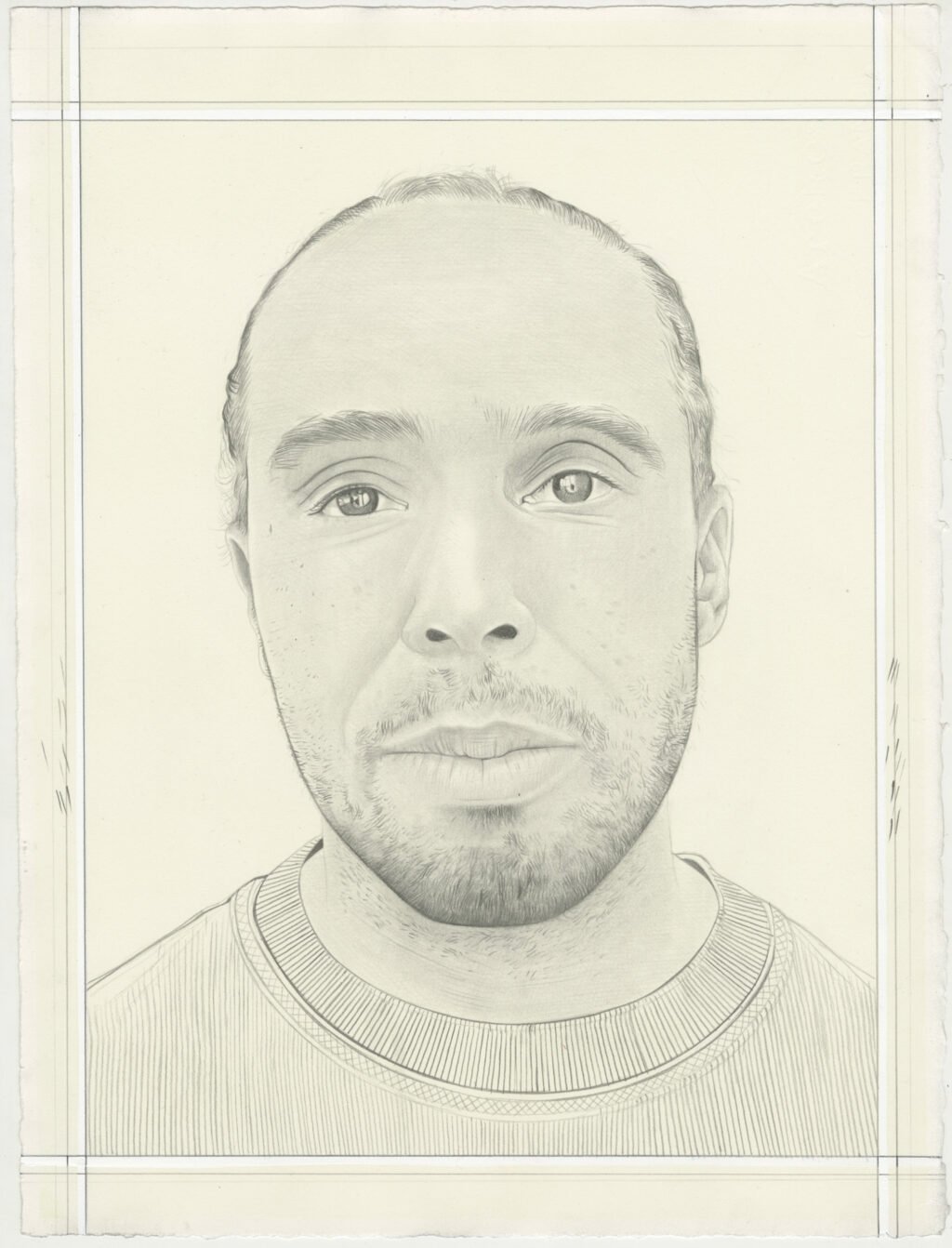

On View

Sean Kelly Gallery

As For Now

May 11–June 22, 2024

New York

Hugo McCloud likes to work with his hands. He’s a builder who thinks about making sculptures the way certain philosophers think about knowledge, as a process. There is no absolute, no certainty; the way the material transforms guides his approach to working with it. In his new paintings McCloud revisits techniques that are nearly a decade old, extending and adjusting his relationship to the tar, metal, oil paint, and wax-paper that he’s become associated with. We met as his paintings were being unboxed. In the conversation that follows, we discuss McCloud’s evolving sense of material, how he understands the balance between excitement and anxiety, and his vision for a future studio practice.

Charles M. Schultz (Rail): So Hugo, I understand this exhibition almost didn’t happen. Can you tell me how it almost went off track, and how you got it back on course?

Hugo McCloud: Well, it almost went off track because I was feeling kind of unsettled in life. I went through some difficult experiences in the last two years, and I had trouble finding personal value and exerting the level of energy and commitment that I exert when I’m doing a show. I always try to evolve the work. That is what drives me into the studio; it’s the only thing that creates excitement. And what I mean by excitement is that I look at inspiration and the idea around inspiration, and what that means as an artist. Who knows how many times a day you’re inspired; when you see something that brings an idea. A lot of people are inspired by a lot of things, but there’s a difference between inspiration and then working through. Once you start working towards that inspiration, for me—and I don’t mean this in a negative manner—you’re problem solving. And once you go into problem solving, that is work. That’s labor, and it’s exertion, and it’s stress, and it’s figuring it out, and it’s waiting.

Rail: You’re tracing an interesting arc between inspiration, labor, and the necessity of waiting. Would you say necessity?

McCloud: Well, just consider the simple idea of waiting for the paint to dry, which is a necessity of the material, and that gives my process some of its form. So what is inspiration doing for you in that moment? It requires discipline. Every time you get a chance to do a show, you want to do your best, and I just didn’t know if I was ready. And I think I didn’t know if I was ready because I didn’t know what I was creating, or what I was even inspired to create because I was just kind of beat down.

The way that our society runs right now is that stuff is very easily forgotten. What you’re doing can very quickly be forgotten because of the sheer amount of information we’re all fed every day. So I reasoned with myself: okay, I am tired. I am feeling this way. But making the show is important. How am I going to do it? I decided to do something different, which was to not invite any input from anyone—no studio visits—until I had the work I felt was right for the show.

Rail: Well, I think the process worked for you. The paintings look great.

McCloud: Thanks. Honestly, I feel like it’s the first time that I’ve been exhausted mentally. But I think that has actually been okay because it goes into where I’m at with the work. And I also think it relates to certain questions we should all be asking, like, what is actually important? Because at the end of the day, there are all these crazy things happening all over the world, and you just bring it back down to a question of humanity—there are people who don’t have food to eat, or a place to sleep, or are in dangerous situations. And you think well, what’s the point of these paintings? And the answer I give myself is that, simply, I believe I was blessed. Even though terrible, crazy-terrible things happened, I was blessed to be in a position that I could start over and continue. It makes me think about my grandfather, and all the other people throughout the world who are just as talented as me—if not more talented—and certain things have happened in their life, and they just have to stop and sit and wait, and then nothing. It’s just completely gone, whatever they were working on is completely gone. My core heart believes that is what art is supposed to be about.

Rail: When I think about your artwork, I think of it as a lot of journeys, a lot of learning, a lot of knowledge, a lot of material manipulation. And that, for me, is all about craft and the connection of your body to these different physical materials. And I wonder, as you approach a decade of making mature work, and returning to some of the processes that you used when you were just getting started—the stamping, the tar paper—what shifted when you went back? I mean, I saw the ornamentation has been removed. What else?

McCloud: So, the plastic work is the first body of work that I’ve created that I need assistance with. Can I do it on my own? Yes, I can. But one, with the plastic work, you can only focus on one piece at a time. And two, it’s very, very labor intensive. You can only do so much in a day. And, frankly, there’s no forgiveness level with it. So it became, during COVID, the thing that we focused on the most, and then it became very successful.

I needed to get back to the tar paintings because for those, it is only me. Nobody helps me with any aspect of the painting or the stamping. There’s never been one stamp painting I’ve done that anybody else has stamped. It’s very personal work. And there’s the freedom of change in it. I can make a mistake, I can change it if I want to, and in that small acknowledgement there’s great freedom, the freedom to explore. And I think what’s shifted is that I really had to find my way back into that.

I’m always tentative of what a lot of other artists have communicated to me, that they’ve done the same thing for such amount of time, and that’s all they’re known for. From the very beginning, I was aware of that contradiction: you want to make something that is uniquely yours, and once you do, you need to move on from it. [Laughter] It’s why I went from the stamp paintings to the metal paintings to the plastic to making paintings of flowers. I think that I needed to explore these different things, but also to be able to have reasons to come back to other ideas.

I let the tar paintings and the stamp paintings rest for a while because there’s real value when you have exhausted the ideas that are in your head at any moment, whether it’s a series or an idea, and you can’t see past that, sometimes the best thing to do is let it rest, because while you’re focused on something else, you can then see what the next move is.

Rail: Was this new body of work, these three bodies of work—your flower paintings, your stamp paintings, and your plastic paintings—made at the same time?

McCloud: Yes, all the work in the show was created within the same time frame. When I don’t know what I’m doing on the paintings, or I’m thinking about how to connect these dots in the plastic work with what’s happening in the tar paintings—that’s when I’m working on the flowers. And while I’m doing the flowers, I’m thinking about the color in the plastic paintings or the stamp paintings.

Doing the plastic work has enabled me to build a lot in my head, because with that work, it’s all about layers. The layers create the different shades that create the different textures. And it starts with the base. So I have to know which layers, I have to know the image that I’m doing. And then I have to think about what in this image I want to portray. And even after that, then it’s like, okay, I want to do it all with a blue tone. So then you’re thinking about what colors of blue and what layers go first. It’s almost like using Photoshop in your mind. During that time I’m able to kind of sit and paint these flowers, or do something that’s intimate where I’m focused and concentrated, I’m sitting. But that’s when I’m reflecting.

Rail: The stamping process seems like it would be very meditative. Is it?

McCloud: It is only meditative because the stamping is a continuous repetition from left to right. And then you start over. So yes, it is meditative in that sense. But at the same time, it’s not easy work. I’ve never started a stamp painting and not completed it in one session. So there’s this level of commitment of doing the whole thing. That aspect works against the kind of serenity that I think tends to be associated with mediative processes.

Japanese sword craftsmanship is actually a pretty good analogy for my stamping process. When those craftsmen are making a blade, they’re smelting the metal and doing the metal work for twenty-four, thirty-six hours—straight. Two or three people are running the kiln; they have to maintain the fire. And it’s all by eye, it’s all by senses. And that’s the same with the stamping. Say while I’m stamping I go kind of light on it, well now I have to ramp it back up to get the impression I want. There’s no going back and fixing this, but I have to create this rhythm, and that’s when you see the flow. Each stamp is a little bit different. You’re hitting the block a certain way, and you’re putting the ink on the block and you’re positioning. It’s like the whole thing becomes this kind of dance of time.

What’s interesting is that I’ve also never done a stamp work that I thought was going to be great from the beginning. I’m always like, “this is trash.” Every time. I’ve never done one that felt different, and it’s so interesting, because not until the very last stamp goes down do you see the imagery. As long as there’s parts of it unstamped, it’s like a naked thing. So I’m always like, “I hope this turns out, I hope this looks good.” I mean you’re standing kind of in this one place, you’re moving very little. But in that time, that’s what you’re thinking about. You’re understanding commitment, you’re understanding the process, you’re understanding the rhythm that you’re creating, and these things are registering whether or not you can communicate it exactly.

Rail: Do you think that level of commitment connects with a kind of faith, for lack of a better word? Because when you commit to something you really have to believe that what you’re going to do is going to be worthwhile. Do you think there’s a connection there?

McCloud: One hundred percent connected. There’s this battle in my head continually—I know what I’m doing is layered and interesting, and I think it’s solid in the context of art. At the same time, I’m continually doubting the value, the execution, the quality of the work.

Rail: Is that tension helpful, do you think?

McCloud: It’s twofold. I think there’s the negative aspect of it that causes you not to appreciate yourself. The benefit of it, I think, is that it also makes you reaffirm what you’re doing. The questioning, being in that zone where I’m not completely sure, that allows me to go the extra mile. But the interesting thing about making art is what we bring to art. I mean, I’m looking at these paintings for however many months I’m making them. I cannot see them from your eyes, or from anyone else’s. So when I look at friends’ art, or I look at artists that I admire, I’m looking at it under the same context that they will see mine—and I’m in awe.

Rail: Who are some artists you admire?

McCloud: There’s a lot of different people for different reasons. I was just at the Broad. And I saw a bunch of really great art, but the one that stood out to me was a painting by Mark Grotjahn.

Rail: Tell me more.

McCloud: Well, it was the first time I saw one of them in person. As somebody who really breaks down materials, I’m able to see the layers in his work. I can see how it must be done in a strategic way, because the colors are not really merged together. And then there’s the simple fact that those paintings are on cardboard.

Rail: Right.

McCloud: That did it for me. The fact that it’s hanging in a museum, this object of cardboard and paint, and we all know what those paintings in museums sell for—to be able to pull that off with those materials, that is special. But I have to step outside of myself, because I recognize that I’m kind of doing the same thing—transforming materials most people would discard into objects people want to hang on walls.

Rail: I want to ask you about Wash and Fold (2024) because it seems like a bridge between your abstract paintings and the figurative work. I initially mistook it for an abstract composition before I recognized it’s an image of laundry.

McCloud: That picture is from a place called Dhobi Ghat, which is in Mumbai. It is one of the largest open air laundry facilities. And what’s interesting about that place, which is usually the underlying narrative of most of my work, is the idea of value. That’s always been the running theme: What do I find valuable? What is valuable in life? What is valuable in the context of everything that we are around? So Dhobi Ghat is kind of in the heart of Mumbai. And surrounding this open-air laundry are a lot of very high-end condos and fancy real estate. And if you think about it, most slums are situated in the heart of valuable property. And then, over time, they’re gentrified, and these places become valuable.

So Dhobi Ghat is interesting because you see this open-air place where people are washing clothes, but you may not realize they’re washing clothes for Soho House, for the hospital, for prominent people, for new clothing brands. They’re doing the pre-washes, and things like that. Originally that was going to be the whole context of the show, this idea of the open-aired laundry, the idea of washing, cleansing. It was me coming out of a lot of stuff and trying to cleanse myself and become fresh.

I also like the idea of clothes drying in the sun, because it leads to the concept of fading. To me fading and things getting old and things being imperfect is a valuable principle. It’s why I don’t try to have things too perfect, because I believe that people, whether they realize it or not, are more comfortable around the imperfect. I think perfection causes people to be uneasy. You know, I think as we get older, we recognize our flaws, we recognize that we’re getting older—my hair is not as thick; my metabolism is not as fast; I’m having heart palpitations—you recognize that life is finite, and fleeting. So to me, perfection only kind of magnifies your frailty. So having things that are also changing and evolving and aging with you is, for me, a comfort.

Rail: One of the simple but profound changes in the stamp paintings is that you’re painting on top of the stamps now, instead of stamping on top of the paint. Seems simple, but you come away with very different surfaces. I’m curious about that decision.

McCloud: I really needed to figure out a way to get out of my own way. [Laughter] With all these bodies of work, whether it’s the metal, or the plastic, or the tar, I’ve created these guidelines that I have to follow. And if I don’t follow them, then it’s not correct. If I’m doing plastic paintings, I cannot add paint. If the guy in the photo I was working from was wearing blue pants, I needed to figure out how to make that color: I couldn’t see outside of the box I created for myself.

Going into this body of work, I had to say, one, I had no desire to decorate. So the idea of doing a stamp with some type of imagery in it was to me a move towards decoration, like I’m going to make this pretty. I always am going towards the idea of beauty, but I need to eliminate the purposeful intention to make something beautiful. I also felt I needed to put myself in a completely unknown place.

And that goes back into the idea of excitement. As an artist, one of the jobs is problem solving. So staying in the zone of “what if” can be healthy and helpful. Until this body of work, I never stamped the paintings first and then tried to figure out, what next? Because stamping was always an act of completion. So once a painting was stamped, I would glue it, mount it, and it would be done. I would put it on a wall and then I had to accept what was there. So stamping it first—doing something that initially always came at the end—created a whole new kind of opportunity. And from there, it was just a matter of figuring it out. I think I’m still figuring it out.

Rail: The three—

McCloud: Can I say one more thing?

Rail: Yes, please.

McCloud: I’ve questioned myself with those paintings where I stamped them first too. Why is this like this? Why didn’t you just make a painting instead of stamping it? I think that the stamping creates something very important. It creates this structure, this grid, almost, where the paintings are really big, but I can break that down into each one of these little, discrete sections. I haven’t really broken down what that means for me, but I think that the stamping creates this grid and this structure, so it’s not overpowering.

Rail: As ridiculous as it seems, I had not yet gotten to the idea of the grid with the stamps. But now that you say it, the paintings of Stanley Whitney immediately come to mind. Both of you employ an edge-to-edge structure that is based on the rhythm of your hands moving across the painting surface. I once asked Stanley where he started, and he told me the upper left corner. Where do you start stamping?

McCloud: Bottom left corner.

Rail: Interesting, maybe because you’re both right handed? Anyway, I want to stay focused on your paintings. One of the things I found really compelling about Blue Zone, Giant Steps, and Visible Exertion (all 2024) are the monotone backgrounds that set off the figure in full color. Can you talk about that choice?

McCloud: Well, it wasn’t originally supposed to be. [Laughter] So this style came up as a way of breaking outside my rules. Like I said before, if I was working from a photo, I needed to stay true to the image. If the sky was blue, I needed to make that sky blue. The concentration was more on how to make this look real than it was on being creative. Why does the sky need to be blue? The sky can be whatever.

So originally, as I said, we were going to make it all color. We were going to go in and add the trees and the buildings and the billboards and all those different things in color. But once we stopped for a second, and we looked at it, it immediately reminded me of the second figure work that I ever made, back in 2019. It’s as if this earlier work was really me trying to get to this new work. You know what I’m saying?

So it’s like, I did choose these different colors, but it was also like, I’m trying to do this as clean as possible. But it’s just so raw, and once I saw that it reminded me to pause, and I thought “let’s be more interesting and creative with this.” And then we went with it. I think at some point this idea could be a whole show. You know, I could do a whole show with just different colors, and that’s it.

Rail: Yeah, you could.

McCloud: Right? So this has also been the anxiety and pressure: I’m painting a lot of different things, and the question becomes, how can I do these different things, and not have it be overwhelming, but fit together. I think this work is also me reaching a kind of phase of maturity as an artist. You come to a place where you start to slow down. You’re not trying to do like fifteen shows plus art fairs every year, which just requires a lot of production. When you look at the trajectories of different artists, sometimes they will work on a single body of work for five years. I think that is also a place where you get out that excitement, and that need, and then you find the rest within your body of work.

And this goes back to a conversation I had with Thelma Golden. What I am trying to create in Mexico is a practice where I’m not working for a show. I’m just working. I’m creating. I’m giving things the time. Yes, I know how to produce, and I know how to edit. But at the same time, what is the value in exploring without the intention of putting it out there? Like what would happen, what would be created? For me it is twofold. I’m excited, I’m energetic; at the same time, I also really understand the value in that other way of thinking. I understand the value of the process of those Japanese craftsmen.

You know that feeling when you hit your goal? And I mean one set purely by yourself, not by others, not about money, but that feeling when you create it and hit it and make something that is really your thing. I think that’s very difficult and hard to find, but that’s the metric I want to be working from.

Rail: We haven’t talked about the room full of flower paintings. Let’s zero in on the three that are unlike the others, the ones on watercolor paper. What’s happening in those pieces?

McCloud: Those are watercolors on wax paper. We use the wax paper—food grade wax paper—to create the plastic paintings. We use it as a barrier between the plastic and the clothes iron. The heat from the iron doesn’t melt it, but it picks up a lot of information from the plastic works because of how we use ballpoint pens to generate the tracings on the plastic to then cut out. So when you’re ironing, it pulls some ink off and transfers it onto the wax paper, which gets wrinkled and torn.

I always had it as a running joke of wanting to do watercolors, because all my work is so labor intensive. You ever talked to other creators who have had an idea in their head for years? And you can have an idea and know it is strong and it’s yours, but it still requires a level of exertion, of energy. I’ve had the idea of watercolors on wax paper for years, I’ve joked around with the galleries for years. But it then required me to go and buy a watercolor set and figure out how to actually use it on wax paper.

The wax paper is a reused material of another process. We mark the date on the wax papers, and the reason why is because they only last a certain amount of time. When we’re making the plastic pieces, we can’t see through the wax paper, so we’ll just grab a new one, and, of course, we never discard that stuff. We hold on to it. So I can relate that flower, which had nothing to do with this representational piece, but I can see the different patterns on it and if I wanted to, I could indicate how this piece of wax paper that makes the flower was first used to make this completely different plastic painting. I think there’s something interesting about that relation of materials, the relation of the pieces, how it’s all connected.

Rail: Do you think you’ll keep making watercolors?

McCloud: These are small pieces, smaller ideas. And this is an object. I’m painting an object. But in my head, I want to take the wax paper, somehow connect multiple pieces, and make a canvas. But then how would I paint on a larger piece of wax paper? Because it wouldn’t be a flower arrangement. So I’m building up the confidence to dedicate the time to figure out how to create an abstraction with watercolor and everything else on this other material.

It’s interesting, because I think when you have twenty pieces of that wax paper, and you have twenty different levels of information from the plastic paintings, you will have all these lines, all these grids, different colorations and text fragments. So now you can kind of create this whole imagery that’s almost like a backdrop for the watercolor, because when you use watercolor, you’re still going to see all that information underneath. That’s where my head is at within the sense of the material. I’m doing the flowers now, but while I’m doing that, I’m trying to see what that is. I don’t have enough confidence yet to dedicate the time to the learning curve, because it’s literally knowing that I’m going to try something and for sure it’s not going to work the first, second, or third time around. And we’re talking about a lot of time. In a sense it goes back into the question of why I stamped the paintings first. Because it puts me in the zone of uncertainty. And I think that at the end of the day that is what creates excitement. And I say excitement in the meaning of willingness to go into the studio and make.