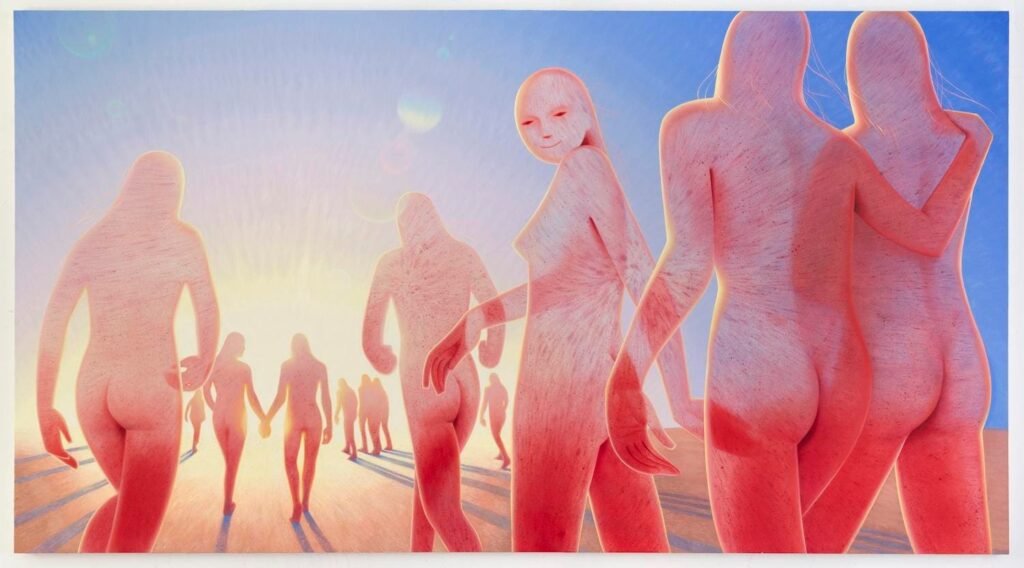

Robin F. Williams, ‘Final Girl Exodus,’ 2021. Oil and acrylic on canvas. 78 x 144 inches. Collection … [+]

As a student at Thomas Worthington High School in Columbus, OH, Robin F. Williams (b. 1984) remembers marching to the principal’s office with her art teacher to defend a painting the school wanted removed from the senior art show. She had copied a painting of a nude woman out of “Art in America” magazine, obscuring the figure’s face with pixelation.

“This was my proto feminist art making practice,” Williams told Forbes.com, chuckling. “I actually received a scholarship for that painting in a competition and it was meant to be honored in the senior art show, but the administration thought that it would be too controversial. My teacher and I had to explain censorship to them, give them a crash course on feminist painting history, and they allowed me to be in the show as long as I wrote an artist statement about why it wasn’t porn.”

Williams didn’t need to defend her paintings with Mrs. Maurer when the Columbus Museum of Art opened “Robin F. Williams: We’ve Been Expecting You,” the first institutional solo exhibition for the artist who depicts evocative figures poised between the real and surreal.

As for the title, it’s not the museum that has been expecting the once-precocious local artist who now lives in Brooklyn to fill its walls, it’s the paintings who’ve been expecting you.

“I like to think of the figures in my work as having some amount of self-awareness or consciousness and it’s a way to play with the power dynamic between the viewer and the figure in the painting,” Williams explains. “Framing the show as a group of paintings that are actually anticipating the viewer, or expecting the viewer, I hope changes the context that you experience them.”

The Columbus Museum of Art

Installation View of “Robin F. Williams: We’ve Been Expecting You.” Courtesy of Columbus Museum of … [+]

Williams began taking art lessons in Columbus when she was five years old. Her grandmother accompanied her. Not fingerpainting or Play-Doh. Oil paint.

“(Painting) has been a lifelong companion and I feel very loving towards it, it keeps being there for me,” she says.

The future artist wasn’t a frequent visitor to the CMA during childhood. One memory of the place she does carry was a visit with her dad when he bought her a book of postcards from the giftshop featuring the work of well-known American painters. George Tooker among them.

“I hadn’t learned to look at paintings in a museum setting, but it definitely sparked something,” Williams said. “I toted (those postcards) around for the rest of my childhood and young adult life because there were paintings in there that really inspired me and were really formative.”

She now hopes to similarly influence another generation of kids from Columbus visiting the museum with her paintings.

“That makes me really emotional, and I have thought about that,” Williams said. “I hope I’m making art that is expansive. I hope (visitors) see my paintings and they make you trust that there are other possibilities, other ways of being, other ways to experience the world that aren’t so narrow or frightening or prescribed. To the extent that I got to see those representations as a young person, they really did help me.”

Williams identifies as queer and non-binary. In her work, she challenges the stereotypical representations of women and sexuality seen throughout art and popular culture.

“As a kid, I was pretty nervous about puberty because I understood that it was going to be this time where I felt that I would have to take on very prescribed gender roles,” she remembers. “There was always some awareness that what was being mirrored back to me didn’t match my felt experience and art making was always a way to sort through that disconnect and make some sense of something that felt off in the world.”

Williams’ work further takes on gendered expectations. She paints men in repose and women reveling in joy without guilt. She does so, unapologetically, as a storyteller, relying on the figure, which wasn’t always as fashionable as it is today.

“I was coming up at a time when narrative in painting was really disparaged. It’s so interesting to watch it explode now because we’re confronting the fact that different identities have been left out of the fine art discourse and some identities can’t be represented without context, without narrative,” Williams said. “I was working with representation and narrative at a time when that was thought to be something separate or not allowed inside of painting discourse. There was always a danger that I was explaining something to the viewer as opposed to making work that’s an experience.”

Robin F. Williams x Marie Laurencin

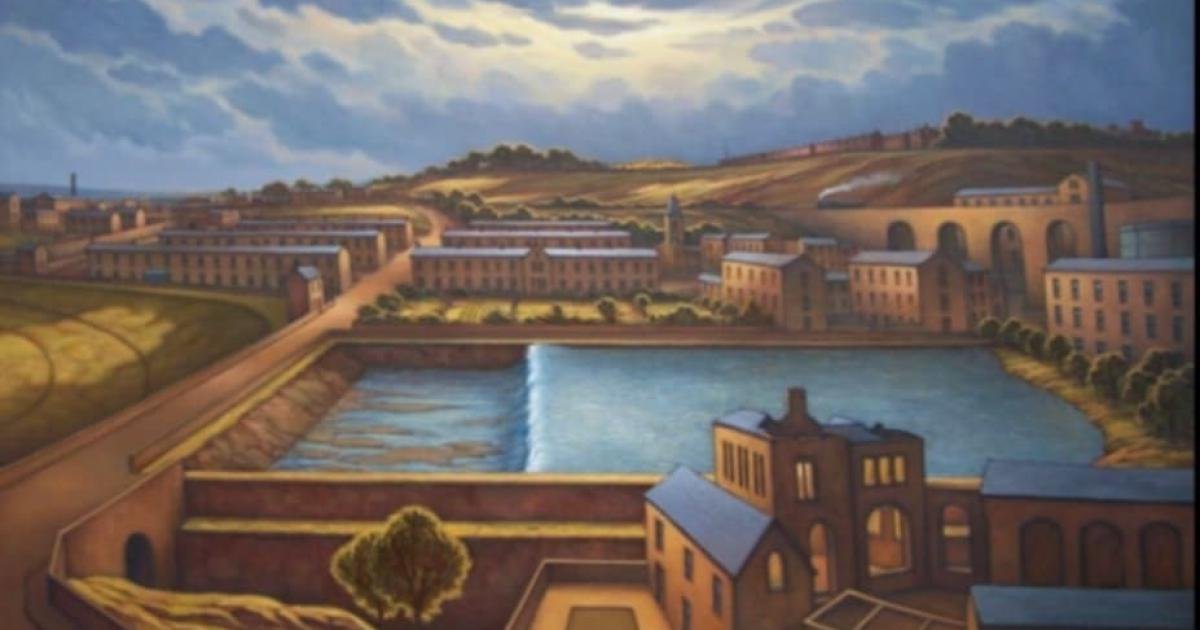

Robin F. Williams, ‘Swoon at the Water Pump,’ 2010. Oil on canvas. Collection of Noel Kiron and … [+]

Williams’ exhibition has been paired in Columbus with “Marie Laurencin: Sapphic Paris.” Both shows opened together and close on August 18, 2024. Though born a century apart on opposite sides of the Atlantic, they share a groundbreaking figurative art practice challenging conventions of femininity and gendered subjectivity.

“It’s amazing to be paired with (Laurencin) in that exhibition space and to be in that context,” Williams said. “She was also a queer artist, a bisexual artist, had a lot of powerful male contemporaries, was living through war, and had many different romances in her life with men and women and kept making art about what her internal lived experience was at a time when it was not necessarily well received.”

Laurencin (1883–1956) was a French painter. The word “sapphic” relates to sexual attraction or activity between women.

The show was hailed when it debuted last year at the Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia. The New York Times gushed, “Laurencin had no interest in adhering to straightforward likenesses. She was interested only in creating an entirely new world.”

As Laurencin’s first major US exhibition in over 30 years, “Sapphic Paris” illuminates the artist’s radically defiant vision, her signature depictions of women in pastel tones and curvilinear forms.

“Sapphic Paris” demonstrates how Laurencin infused a feminine, queer aesthetic into the artistic currents of her era. From initially establishing her practice in prewar Paris, fleeing to Spain during World War I, and subsequently returning to Paris in 1921, Laurencin came to play a definitive role within the cultural milieu of 1920s Paris. In the decades to follow, Laurencin created intimate bodies of work in conversation with contemporary sapphic literature, comprising a transformative lens into “sapphic modernity.”

Both exhibitions advance the Museum’s stated aim of forwarding queer voices in Modern art, and hosting Williams continues its deep engagement with the greatest artists possessing backgrounds in Columbus, a roster including George Bellows, Roy Lichtenstein, Elijah Pierce, and Aminah Brenda Lynn Robinson.