Has the Francis Bacon cult peaked? For most of the second half of the 20th century, the Irish-born painter’s unstinting bleakness, ravaged flesh and sado-masochistic homoeroticism made him the outrage king of British art. Think Damien Hirst to the power of 10. The very mention of Bacon’s name induced a shiver up the spine, among fans as much as detractors. If the 21st century brought Bacon retrospective acclaim as the greatest British artist of his time, it also gave him perhaps too much acceptance and familiarity. Thirty-two years on from Bacon’s death, this major exhibition featuring 58 paintings is an opportunity to assess if the artist described by Margaret Thatcher as “the man who does those dreadful pictures” is still a unique figure, who hits us on levels other artists don’t reach.

Bacon on the face of it is a no-brainer for the National Portrait Gallery. Just about everything he did was to some extent a portrait. Yet besides the symbolic depictions that made him famous – the notorious screaming popes and sinister images of anonymous, besuited men – there are many portraits of actual people. The news that the NPG’s show groups its exhibits around particular individuals who sat regularly for Bacon and with whom he remained preoccupied for decades – including Lucian Freud, Soho’s Colony Room proprietor Muriel Belcher, and his petty criminal lover George Dyer – suggests we could be in for a rather gossipy, lightweight show. Such an exhibition would almost inevitably focus on the latter stages of Bacon’s career, when his signature “tortured” style had become a shade mannered and repetitive.

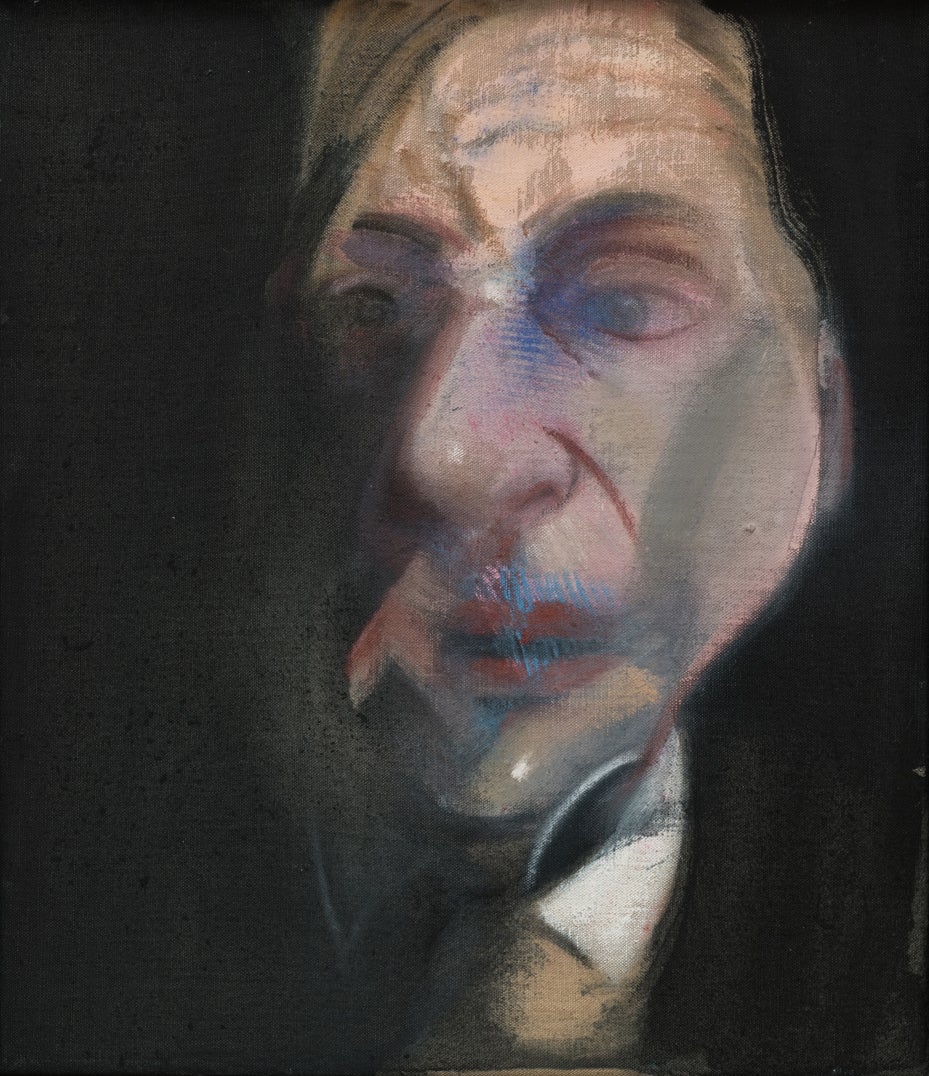

Certainly, the opening painting, the small Self-Portrait from 1987, shows Bacon at his absolute worst. With his melancholy, introspective expression rendered in muted pinks and fuzzy contours, it looks like a prettified pastiche of Bacon rather than the real thing.

Thankfully though, the show doesn’t take the notion of portraiture too literally and makes space for some cracking early “studies for portraits” in which anonymous male figures merge with some of the second-hand images that obsessed Bacon for decades.

In Study for a Portrait (1952), the gaping mouth and shattered glasses of a woman shot in the eye in Eisenstein’s silent film classic Battleship Potemkin (1925) are transposed onto the features of a smartly dressed male. He could equally represent a conventionalised power figure, such as a politician, and the kind of nameless businessman Bacon encountered in amorous trysts whose joyless, alienated quality was all part of their appeal for him.

In Head VI (1949), this screaming face is grafted onto an ecclesiastical figure inspired by Velasquez’s magisterial portrait of Pope Innocent X, of which Bacon made 50 interpretations over two decades; paintings regarded by many as his greatest works. Two more examples, both lesser known, are included here. The frankly bizarre Study for Portrait (with Two Owls) (1963) in which the birds perch on a transparent box, while the pontiff’s face is broken into a mass of black calligraphic marks definitely gave me that quintessential Bacon spinal tingle.

When Bacon gets to portraits of actual people there are few concessions to likeness, let alone flattery. In Portrait of RJ Sainsbury (1955), Robert Sainsbury of the grocery dynasty, sits in the dead centre of a large black ground, deathly pale in black tie, looking like some punch-drunk undertaker.

Even more powerful is the large Man in Blue I (1954), in which the besuited subject leans on a bar in a cavernous, deserted space, his pale features looking as though they’ve been gouged out with the hard end of Bacon’s paintbrush. According to the text panels, it may show Peter Lacy, a troubled, directionless character whom Bacon considered the love of his life, and with whom he had a tempestuous, often violent relationship. It may also allude to the travelling salesmen Bacon observed at a hotel near Lacy’s home at Henley-on-Thames. For Bacon, the “traveller”, always on the move between bleak hotels, represented both the alienation of modern man and the possibility of erotic encounters on the road.

Bacon exhibitions routinely astound in the first half and disappoint in the second. Francis Bacon: Human Presence contains enough variety of works in its climactic sections to account for the stronger and weaker aspects of the later Bacon, while veering thankfully towards the former.

Three Studies for a Self-Portrait (1980) inspired by “the way in which paint and subject coalesced”, as the wall texts have it, in Rembrandt’s self-portraits doesn’t come near Bacon’s own best work, never mind Rembrandt’s. Indeed, the careful, even tight-arsed handling of the circular forms protruding from the artist’s face contradicts everything we understand about the “wildness” of Francis Bacon.

In Study for Three Heads, painted 18 years earlier in exactly the same format – shortly after he learned of Lacy’s alcohol-induced death – the features have exactly the kind of bludgeoned, raw-meat quality we expect from Bacon. Yet even here the handling of the paint is, on close inspection, quite meticulous. I suspect that Bacon’s painting was never as wild and let-it-all-hang-out as we like to imagine.

Study for Self-Portrait (1964), which grafts Bacon’s squidgily rendered head onto his close friend Lucien Freud’s body, is a reminder of how hit-and-miss Bacon’s technique could be even in his heyday. Freud’s arms are rendered in generalised looping forms reminiscent of a Popeye cartoon. If that work is a resounding miss, Portrait of Isabel Rawsthorne (1966) is a genuinely great modern painting, the features captured in a mass of curving shapes that convey a sense of fractured movement in space, while feeling somehow timelessly elegant.

The final space, devoted to images of George Dyer, an East End burglar with whom Bacon had a troubled, often violent relationship (well, there’s a surprise), sums up the pros and cons of Bacon’s art. Everything falls at a glance into the limited emotional range we’ve come to expect from him. Yet there’s something to startle and surprise even the seasoned Bacon viewer in every painting. In Portrait of George Dyer Riding a Bicycle (1966), Dyer with his distinctive hawk-like profile – with which Bacon was obsessed – appears to cycle across a tightrope, parts of the bike rendered in massively thick smears of white paint. It’s an Abstract Expressionist touch that doesn’t fit with most people’s ideas of Bacon.

In Portrait of George Dyer in a Mirror (1968) the subject appears sliced in half and cursorily reassembled, with his missing face dismembered, but all too clearly visible in the adjacent mirror. In the monumental triptych filling the show’s final wall, entitled Triptych May-June 1973 (1973), Bacon who, we are told, “disliked narrative reading of his painting”, paints his lover’s imagined last moments during his suicide by overdose in a Paris hotel room. We see Dyer slumped on a toilet in the left-hand canvas, vomiting blood on the right, and staring into space at the centre, a black shape that might be construed as representing his imminent death splurged across the floor in front. Bacon created this startlingly frank work very soon after the event, and while portraying an intimate in such brutal terms might be seen by some as callous – to put it mildly – I don’t doubt that Bacon saw it as an act of love. The aim of his art was, he said, to “return the onlooker to life and more violently”. After all the supposed outrage we’ve seen in art over the past 20 years, there are plenty of works in this essential exhibition that fulfil Bacon’s ambition even now.

Francis Bacon – Human Presence runs from 10 October until 19 January 2025