Our impressions of “Scandi culture” may come and go – with baking and “cosiness” having dominated of late – but the appeal of Edvard Munch’s tormented Nordic visions never wavers. Even more than Ingmar Bergman’s films or all those edgily stylish Nordic noir thrillers, the Scream artist nails our sense of something sinister and claustrophobic at the heart of the land of the midnight sun.

Yet alongside this intensely personal imagery, prompted by the “dark angels” that accompanied the Norwegian painter throughout his life – “illness, madness and death” – Munch was also a prolific painter of portraits, many of them commissioned by wealthy businessmen and other public figures. They are images that reveal, this exhibition argues, a more sociable and worldly side to an artist who tends to be thought of as solitary to the point of mania.

This first British exhibition to focus on Munch’s portraits brings together 40 paintings, from small student works and polished “swagger” portraits to more personal works in which he seems to look simultaneously outward towards real people and inwards at his personal demons.

Aside from a cocky self-portrait painted when he was 19, his earliest works are small and almost puritanically self-effacing. You’d never suspect from his meticulously detailed image of his bearded father smoking a pipe that the subject suffered “bouts of nervousness and extreme religious anxiety”.

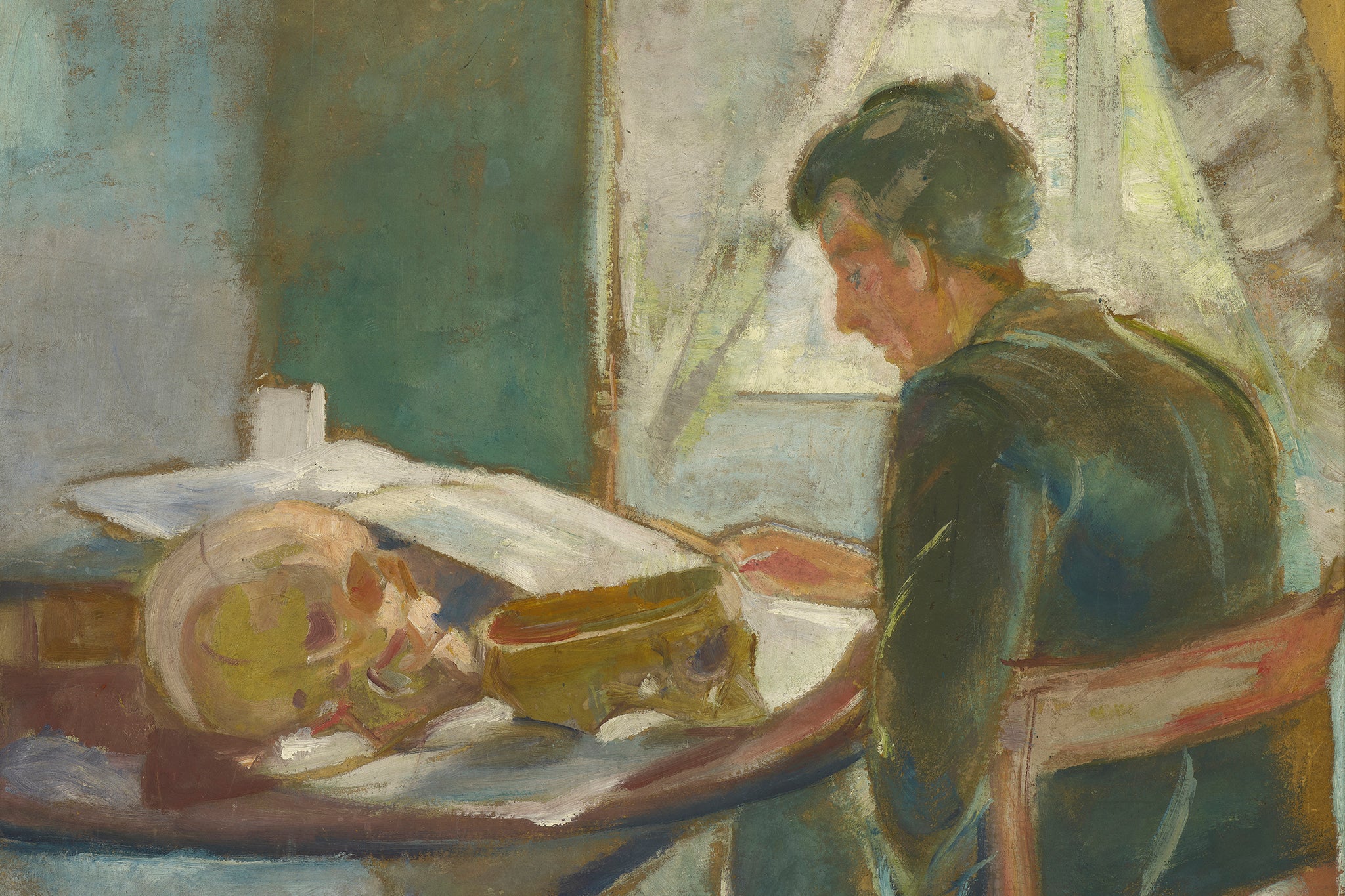

The equally tiny, but more loosely painted portrait of his “marvellous aunt”, Karen Bjolstad (1885) brings a sense of typical Munch introspection, though perhaps only because she happens to be looking down to read. If there’s the hint of a Nordic Cézanne in Anders Munch Studying Anatomy (1886), with angled planes of light illuminating the room where his doctor younger brother is reading, it’s Evening (1888) that confirms we’re looking at a totally extraordinary artist. Showing Munch’s troubled younger sister Laura seated outside a rented holiday home, it could pass for a pleasant enough Post-Impressionist seaside view until we notice the young woman’s manic gaze staring off to the right of the painting. Evening, we’re made to feel, is a time when the feverish tensions beneath the everyday world come to the surface.

From here on the exhibition is a matter of picking apart the elements that feel uniquely Munch and those that conform to the expected norms of portraiture. Hans Jaeger (1889) is a tough, no-frills image of the charismatic nihilist leader of Oslo’s bohemian set, slumped on a café sofa. Remarkably direct by the standards of the time, it doesn’t seem so startling to modern eyes. Munch’s full-length image of fellow painter Karl Jensen-Hjell (1885), produced for the cost of materials and a meal at Oslo’s Grand Hotel – such was the 22-year-old artist’s need at the time – feels like a shaky take on classic society portraiture, like something the stuffy Victorian portraitist John Singer Sargent might have produced after a few too many glasses of absinthe (Munch’s favourite tipple at the time). It was condemned by critics as “a raw spluttering on canvas”.

Another full-length portrait featuring Daniel Jacobson, who treated Munch in his Copenhagen “nerve clinic” after the painter’s alcohol-induced nervous breakdown, was written off by its subject as “stark raving mad”. Munch, who resented the doctor’s controlling attitude, wrote that he had portrayed him in a “big and dominant” male pose, with legs apart and hands on hips, in a turquoise suit that vibrates against a swirling yellow and red background designed to evoke “all the fires of hell”. Seen now, stripped of Munch’s vengeful connotations, it appears a great piece of proto-Expressionist painting.

As Munch’s career progressed to large-scale portrait commissions there’s an even more jarring contrast between conventional, even conservative compositions, with smartly suited men in highly polished shoes striking dashing poses, and hallucinatory colour. His portrait of art critic Jappe Nilssen would appear painfully ordinary if it weren’t for the subject’s eye-popping purple suit and shimmering green background. Indeed, the treatment of the face is so conventionally realistic that you’re left wondering if Munch was aiming for heightened, visionary colour or the subject just happened to be wearing a purple suit.

The boundaries between the conventional and the experimental dissolve in the final room, where the rendering of the figures loosens up and the colour sings ever more strongly, in works from the later 1900s and 1920s. Munch himself turns towards us, mid-conversation, against a zinging yellow background in Torvald Stang and Edvard Munch (1909-11). Seated Model on the Couch (1924), with its vibrant washes of red and blue, brings to mind Matisse’s fauvism 20 years after the event, but much more loosely painted and with a subtle Nordic tinge.

The room is called “Friends and Guardians”, focusing on a network of friends and patrons who gathered around Munch in his later years of acclaim. Other sections are called “Patrons and Collectors” and “Bohemia”, underlining the show’s argument that Munch’s portraits “foreground his artistic and business networks, as well as deep and lasting relationships” – as though Munch consciously set out to document these milieus. While that is, I dare say, arguable, the enormous amount of sociohistorical information in the wall texts threatens to suffocate the paintings as experiences in their own right – as though they’re there principally to illustrate the biographical details.

At the same time, there’s almost no attempt, apart from a reference to the patently Van Gogh-like qualities of Felix Auerbach (1906), to contextualise Munch in terms of the momentous developments happening in art elsewhere – notably Paris – at the time. Once again, Munch is presented as an isolated figure doing his own variants on Post-Impressionism, Symbolism and Expressionism on the northern fringes of Europe – never mind that much of his most important work was done while living in Berlin.

.jpeg)

Yet this is without doubt an essential exhibition. And some of the most revealing works are some of the earliest, though because of the layout, we’re most aware of them when leaving: prints and paintings from Munch’s classic Scream period, from the very familiar – Henrik Ibsen at the Grand Café (1902) – to the relatively little-known Aase and Harald Norregaard (1899). It’s in these works that we most feel that charge of mysterious neurotic energy we think of as quintessentially Munch. No matter how many other aspects of Munch’s art we’re shown, this is the one we’ll keep coming back to.

Edvard Munch Portraits is at the National Portrait Gallery from 13 March until 15 June