A new scientific study is challenging long-held beliefs about Jackson Pollock and his iconic “drip paintings,” suggesting that the Abstract Expressionist may have embedded hidden images, or what researchers call “polloglyphs,” into his compositions. While some experts argue this is merely a case of pareidolia—seeing patterns in randomness—the findings reignite debate over the psychological depth and hidden symbolism in Pollock’s revolutionary art.

Pollock became a leading figure of the Abstract Expressionist movement in New York when he began making his “drip paintings” in the late 1940s. His signature style included flinging, pouring, and splattering paint onto unstretched canvases laid on the floor. Art historians have generally dismissed the possibility that there is any representational aspect to these works, but a new scientific study suggests that the artist, whether consciously or unconsciously, filled his compositions with repeated images of monkeys, clowns, and bottles.

Critical to this theory is the researchers’ posthumous diagnosis of the artist with bipolar disorder, which they categorize as a serious mental illness (SMI). Led by Dr. Stephen M. Stahl, an adjunct professor of psychiatry at the University of California, San Diego, the research team noted how the artist suffered from mood swings, social anxiety, and alcoholism in a paper published last month in Cambridge University Press’s CNS Spectrums. The artist also had regular sessions with a psychoanalyst from the age of 23.

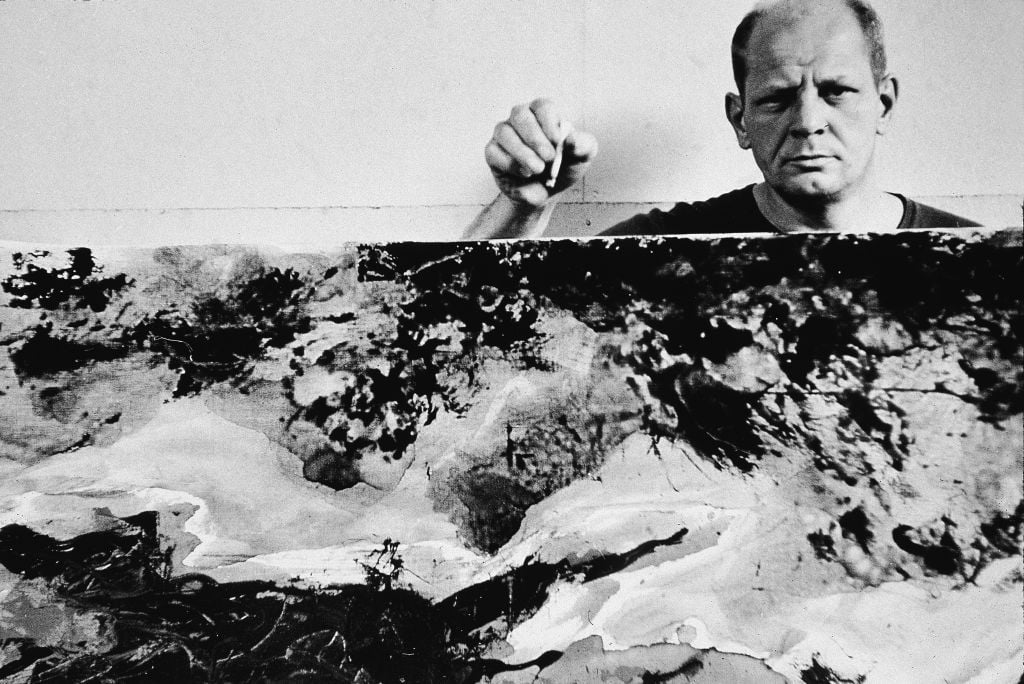

Jackson Pollock in his studio in East Hampton, New York, in 1953. Photo: Tony Vaccaro/Getty Images.

“The question arises whether his SMI played any role in the way he created his drip paintings, especially when he was overactive and manic,” the scientists said. “Furthermore, did visual hallucinations or enhanced visual perception associated with mania or psychosis facilitate Pollock in embedding and camouflaging images under layers of thrown paint?”

The researchers refer to these “recognizable” images as “polloglyphs,” and believe that they may have been camouflaged by Pollock’s “drip technique.” They claim, for example, that the 1945 work Troubled Queen can be rotated to reveal various images, including a “charging soldier holding a hatchet and a pistol with a bullet in the barrel; a Picasso-esque rooster; a monkey with goggles and wine; and one of the clearest images, the angel of mercy and her sword.”

Meanwhile, an untitled 1949 work at the Fondation Beyeler in Switzerland apparently shows Pollock “with his signature baseball cap looking at something with a magnifying glass; a monkey with his arm around Pollock looking on; and also those notorious booze bottles.” The researchers call the composition Monkey on My Back.

Yet the paper’s authors acknowledge that “seeing images in Pollock’s drip paintings has been a controversy ever since these paintings were created.”

Indeed, art historian and critic Clement Greenberg was a key champion of Pollock’s in the 1940s and ’50s. Greenberg believed that the logical and necessary end of modern art was pure abstraction, rendering art emptied of any historical or symbolic representation. In a 1952 ARTnews article, Harold Rosenberg coined the term “action painting” with Pollock in mind, and wrote that “what was to go on the canvas was not a picture but an event.”

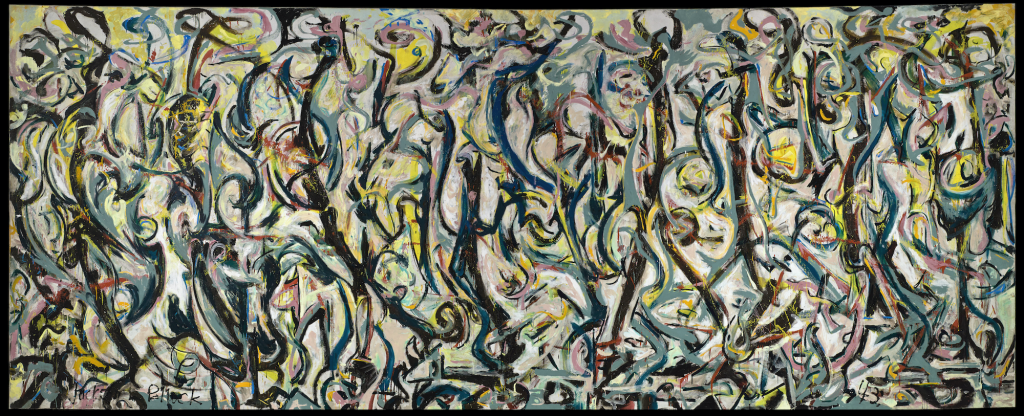

Jackson Pollock, Mural (1943). University of Iowa Stanley Museum of Art, Gift of Peggy Guggenheim, 1959.6 © 2020 The Pollock-Krasner Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Yet, in a 1972 issue of Artforum, writer Judith Wolfe said that Pollock was well acquainted with Jungian psychology before many of his peers, citing his experience with several psychoanalysts. She argued that the importance of Jung’s archetypal symbolism “has not been sufficiently explored, nor has it even received proper credit as a motivating force within [Pollock’s] development.”

Was Pollock really embedding this array of complex imagery into the works as he hurled paint at the canvas? Or is it possible that the perception of these images could be an act of projection on the viewer’s part?

“Some experts attribute this to pareidolia—perceiving specific images out of random or ambiguous visual patterns—a phenomenon known to be enhanced by fractal fuzzy edges such as seen in Rorschach ink blots as well as in Pollock drip paintings,” Stahl and his researchers said in their paper.

The authors, however, argue that this pareidolia is “very unlikely” to be the explanation for these images because some polloglyphs appear repeatedly in several works. These include wine bottles, clowns, monkeys or gorillas, and elephants. The researchers have suggested a possible source for the images, which they say are reminiscent of figurative sketches Pollock made in 1936, at the instruction of his first psychoanalyst, Joseph Henderson. The example provided in the paper is titled Drunken Monkey by the researchers, and features “a monkey with glasses” that is “holding a wine bottle with another booze bottle visible.”

The authors posit Pollock’s “remarkable ability” to hide the images in plain sight “may have been part of his creative genius and could also have been enhanced by the endowment of extraordinary visual spatial skills that have been described in some bipolar patients.”

The researchers remain unsure whether these perceived images were introduced by Pollock intentionally or unconsciously, ultimately concluding that “we may never know if there are polloglyphs present in Jackson Pollock’s famous drip paintings.”