The pioneering Photorealist painter, sculptor and feminist image-maker Audrey Flack died on 28 June in Southhampton, New York. Her death was confirmed to the public by her former dealer and friend, Louis K. Meisel, as well as Hollis Taggart, the gallery that has represented her since 2015.

Flack is survived by her two daughters from her first marriage, Melissa and Hannah, and stepchildren Mitchell and Leslie. Her second husband and high school sweetheart, Robert Marcus, preceded her in death in May of this year.

Audrey Flack, Jolie Madame, 1972, Oil on Canvas, 71in x 96in, National Gallery of Australia Hollis Taggart

Flack was born in New York in 1931. She attended New York’s High School of Music and Art before studying at the Cooper Union; later Josef Albers, the luminary of geometric abstraction, recruited her to the Yale School of Art. Soon, Flack was immersed in the downtown New York arts scene, cutting her teeth at New York’s Art Students League and socialising with Abstract Expressionist giants like Willem de Kooning and Jackson Pollock (the latter of whom she romantically rejected).

During the 1960s, Flack’s development of a distinct Photorealist language all her own constituted a visual sea change both in the genre and in the evolution of her practice, guiding her hand away from the masculine bravura of Abstract Expressionism and into a more vulnerable, explicitly feminist realm. Her seven-decade career included countless exhibitions and has seen her work acquired for many important institutional collections including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Her personal papers will soon be included in Smithsonian Institution’s Archives of American Art.

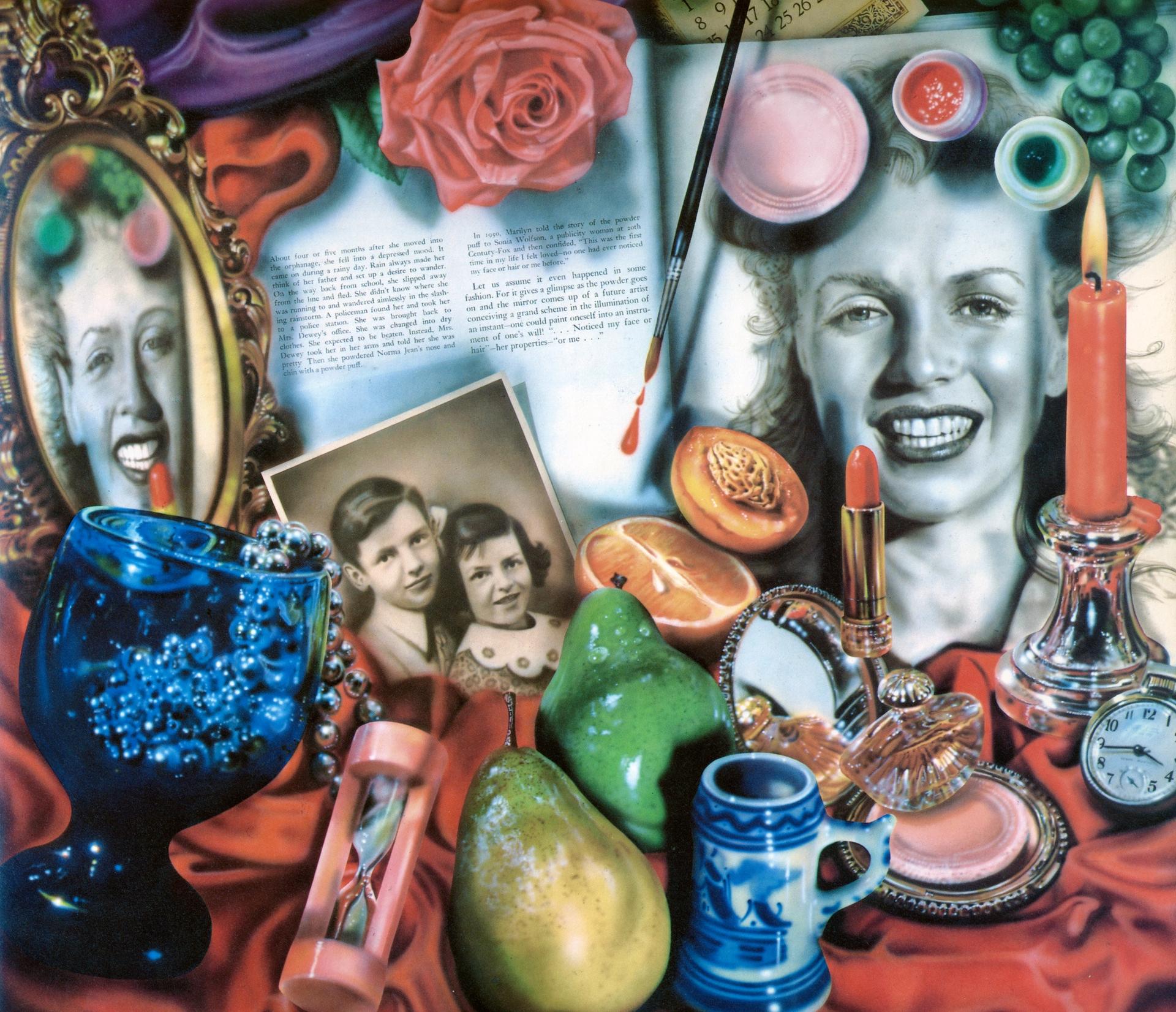

Audrey Flack, Marilyn (Vanitas), 1977, University of Arizona Museum of Art Hollis Taggart

Flack is best known for her big, bright, busy still-lives, depicting personal tableaus imbued with the gravity of religious altars. Juxtaposing art historical symbols like memento mori skulls with tarot cards, jewellery and tubes of lipstick, her self-consciously feminine compositions ruffled feathers in the art critical sphere, earning her the moniker “the Barbra Streisand of Photorealism” from Hilton Kramer in a 1976 review for The New York Times that railed against the Museum of Modern Art’s decision to include her as the first Photorealist artist in its permanent collection. While other titans of the movement like Richard Estes and Robert Cottingham preferred hard-lined urban and industrial subject matter, Flack’s emotive, intimate pieces elevated her voice beyond the confines of the movement she helped create.

By the late 1980s, Flack had started experimenting with three-dimensional work, producing large-scale bronze sculptures of female goddesses. In a 2012 review of a bronze-centric exhibition of Flack’s at Gary Snyder Fine Art for Artnews, Cynthia Nadelman called her sculptures “fun and awe-inspiring”, lauding her “defiant and sometimes winking appropriation of the ups and downs of figurative sculpture”.

Audrey Flack, Beloved Woman of Justice, 2000 Hollis Taggart

“Audrey’s boundless creativity defined her career, spanning seven decades, constantly innovating and searching for new ways of expression, from early years of Abstract Expressionism, to mid-century figuration, to Photorealism and culminating in her final chapter of ‘Pop Baroque’,” Hollis Taggart said in a statement. “Her acclaimed memoir, published only months before her passing, reveals her true spirit and her ability to overcome all obstacles and achieve her ambitious goals. She will be dearly missed.”

In May, Flack published With Darkness Came Stars, a memoir reflecting with humor and rhetorical flair on her long career, her abusive ex-husband and the challenges of raising a nonverbal daughter with autism. She described her patchwork visual record of her life experiences as “timestream”, attributing the signature luminous quality of her paintings to her eyesight, writing: “My eyes were great, I had incredible vision. One eye saw with blue hues and the other eye saw with warmer. I was a colourist. […] What’s surreal for me is what’s happened to the way I see the world. My colours have gotten brighter and lighter. That’s surprising.”

Chloe Pickoff, Flack’s studio manager, told The Art Newspaper in a statement: “In four words, Audrey described herself as artist, mother, teacher, rebel. She was truly all of that, but additionally, she was endlessly an explorer, and I’m proud to say a dear friend. There are very few people I have been able to speak so deeply about art with and explore alongside so collaboratively—and I witnessed so many other people she made feel this way, from her students to fellow artists and other members of the creative community. I was fortunate to have experienced so many of these conversations over the time we learned and worked together.”

This autumn the Parrish Art Museum in Water Mill, New York, will open a survey of her recent work, Audrey Flack: Mid-Century to Post-Pop Baroque (13 October-6 April 2025).