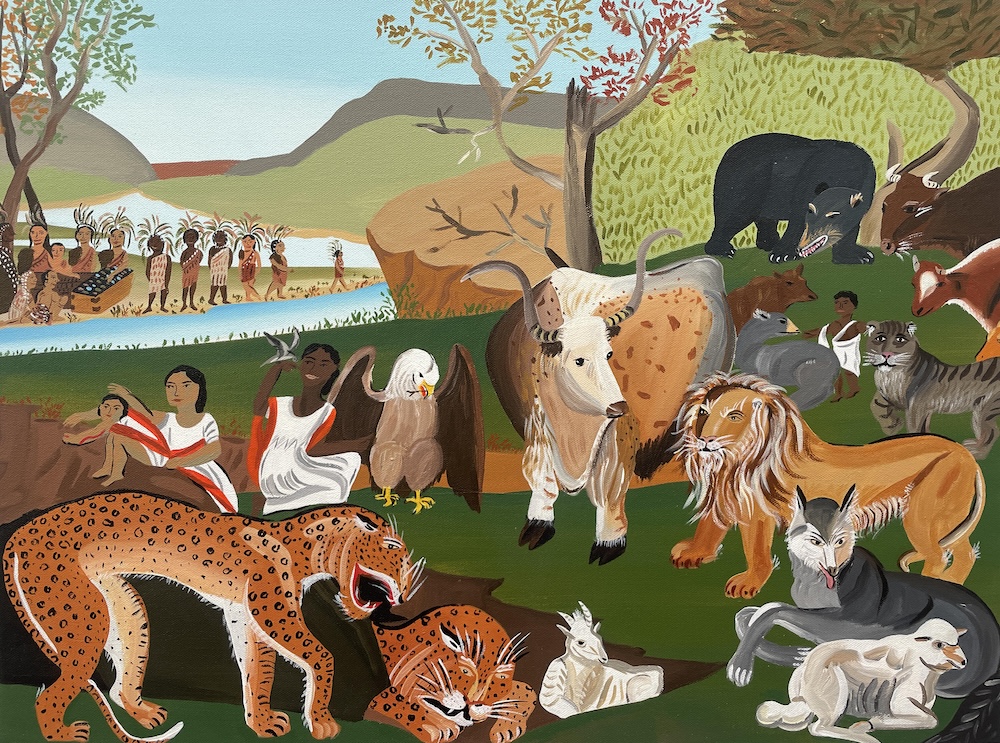

As part of his wide-ranging and often interactive de Young Museum show—and his first major US exhibition—Rituals of Care (runs through July 7), Taiwanese artist Lee Mingwei asked local artists to reinterpret Quaker minister Edward Hicks’ 1846 painting Our Peaceable Kingdom, which depicts a prophecy from The Book of Isiah: “The wolf also shall dwell with the lamb, and the leopard shall lie down with the kid.”

Perhaps more concretely, the work—of which Hicks made a vast number of versions—portrays the 1682 purchase treaty that the Quakers’ William Penn signed with the Lenape Delaware peoples. Though Penn apparently respected the terms of the treaty throughout his life, Hicks was witness to how successive generations did not always co-exist with the Lenape Delaware governed by Penn’s promise of friendship, mistreating and eventually displacing them from their lands.

Lee’s artistic project includes “asking how art can encourage social connection and healing in a time of so much trauma and loss.” By asking artists to reinterpret Hicks’ painting, and then they in turn ask fellow artists to do the same, Lee creates “a family tree of copies with multiple descendants.”

In total, 16 artists delivered their takes across 39 canvases on this fraught capture of colonial history. Painter Chelsea Ryoko Wong approached her reinterpretation by breaking down the piece and painting from the background to the foreground. Subsequently, two more artists drew from her work, alongside the museum’s copy of Hicks’ Our Peaceable Kingdom, to create their own reinterpretations; Emily Fromm and Emilio Villalba.

In an interview with 48hills, Wong said it felt like a big ask to paint peace. She thinks of painting as problem solving, but she wasn’t sure where to start when copying someone else’s work. So, she did what she would normally do—start with the background, move to the foreground, and set goals for herself. In this case, that meant painting a certain number of animals a day.

“I looked at the painting, and I’m like, ‘OK, there’s this kind of valley in the background, and the horizon line on this valley, and these clouds and these trees and these people,” Wong said. “I blocked out the proportions of the grassy hill and the mountains and the sky and the water. Then I moved to the animals, and I kind of just worked from left to right, like ‘If I start out with the cheetahs on the lefthand side, I can go to this goat, and then to the fox.’”

Then Wong painted the figures—angels, a woman with a bird, and a baby—petting the animals. Last, she painted the Lenape people. Here, she particularly diverged from her source material.

artist Chelsea Ryoko Wong

“In [Hicks’] painting, they are literally painted with red paint, so I changed that around,” Wong said. “It feels like time to kind of correct some of these things that felt jarring to me.”

Though she worried a little about changing the original too much, she says was ultimately pleased with her version.

“A lot of times while I was doing this, I was actually thinking about the history of what happened between them and how it wasn’t peaceful,” Wong said.

For her interpretation, Fromm referred to Wong’s painting as well as the original. She noticed that the original features a lack of confrontation. Its animals, including a lion, a sheep, a cow, and a bear, mostly face the viewer, not one another. A lot of Fromm’s work deals with urban scenes, for which she typically uses lots of red, blue, and grey. She changed that for this work, using teals and greens, trying to make it more “of the earth,” she says.

Villalba was struck by the use of negative space and the rhythm of the original painting.

“There’s movement with all the animals and landscape and the figures in it, and in my mind, I just combined all that,” Villalba said. “I remember specifically trying to just kind of mash them and overlap some of the figures a bit, kind of like an MC Escher.”

As he often does in his work, which is inspired by Bay Area figurative artists like Richard Diebenkorn, Joan Brown, and David Park, Villalba used thick layers of pigment.

Emilio Villalba

“I really like the way my paintings look when they have more paint,” he said. “It’s like eye candy, I think, and I just keep building it up every year.”

He included an angel translated directly from Wong’s version. He added a small Sutro Tower, along with a couple other changes, in a nod to San Francisco.

“In the original, it looked like they were selling or trading slaves” Villalba said. “I just thought of new trade, so I put a container ship to replace the ship, and then I put a computer there to symbolize capitalism or colonialism. Then right next to the computer, I put a self-portrait me in red, and then a portrait of my wife Michelle.”

At first copying a painting felt odd to Villalba, but he’s proud of what he created.

“I was telling my wife that I’ve been painting my own work for so long now, and this is almost like doing a cover song,” he said. “The composition is already there; the colors are already there. Everything’s there for me. I just had to do it in my style.”

Fromm loved seeing all the different versions at the de Young.

“Emilio’s and Chelsea’s interpretations were just so incredible and bold and unique, and I love them,” she said. “It was just surreal, wandering through all the paintings. There are so many different ways that you could have gone with it, so many different paths that could be taken. I’ve gone back a few times and looked through each one multiple times.”

RITUALS OF CARE runs through July 7. de Young Museum, SF. Tickets and more info here.