One of America’s most important and influential landscape artists was a free Black man in the 1800s who spent decades creating in Detroit and even died here. Yet many still don’t know his name.

Robert S. Duncanson was widely considered “the best landscape painter in the West” in the years surrounding the Civil War. Born in Fayette, New York in 1821, he was brought with his family to Monroe in 1928. Ten years later, he and a partner began a painting business; Duncanson would spend the rest of his career as an artist.

Modest beginnings

Unlike most Black people in America at the time, Duncanson ‒ the son of a freed Virginia slave ‒ was never enslaved. In 1840, at 19, he moved to Cincinnati. At the southern border of free Ohio, just across the river from slave-owning Kentucky, the city was considered a place where the Southern way of life existed on liberated ground and was a major stop on the Underground Railroad, with the Ohio River crossing viewed by many slaves as the last obstacle on the path to freedom.

Abolitionist author Harriet Beecher Stowe, a Cincinnati resident, witnessed many horrific examples of slave families being separated and sold on the Ohio River, which fueled her tremendously successful 1852 anti-slavery novel “Uncle Tom’s Cabin.” In one scene, runaway slave Eliza traverses the perilously icy river to escape to freedom.

In 1853, Duncanson was commissioned to provide illustrations for a reprint of the book. His “Uncle Tom and Little Eva” from that venture is just one piece by the artist on display at the Detroit Institute of the Arts (DIA), where an entire gallery is dedicated to his work.

Cincinnati’s position at freedom’s finish line made it one of the country’s largest Black communities; its overall population nearly tripled between 1840 and 1850, bringing with it even more freed Black people.

Duncanson moved there for its reputation in the arts world —19th century Cincinnati was known as “the Athens of the West” — and it was there that the untrained artist began to study his trade. He fell in with well-to-do abolitionists who supported his endeavors and would eventually fund him on European tours where he studied the Old Masters and wandered the continent’s abundant countrysides, producing new and evolved work.

Presidential recognition

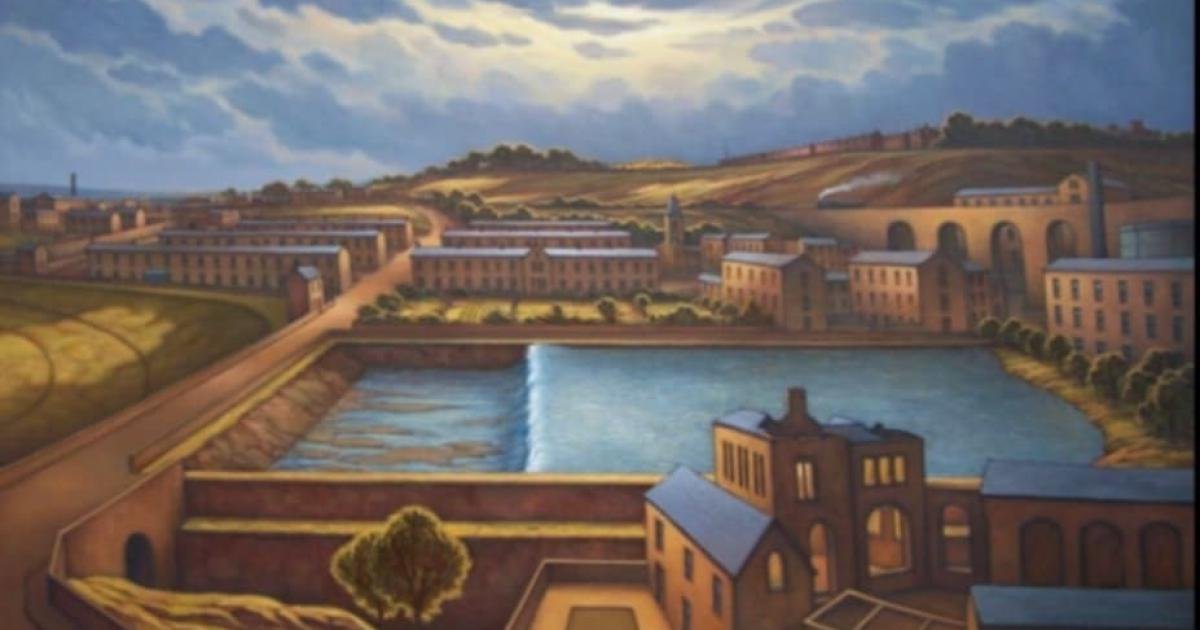

The vista in “Landscape with Rainbow,” inspired by the undulating terrain of Cincinnati, was selected in 2021 by Dr. Jill Biden to hang in the Capital rotunda in Washington, D.C., during President Joe Biden’s inauguration ceremony.

Borrowed from the nearby Smithsonian American Art Museum, the pastoral work, in oil on canvas, depicts a young couple and their dog wading through a shallow, sun-dappled stream amid verdant meadows dotted with hearty trees and cattle gently grazing as they head home for the evening. In the distance, rolling hillsides surround a lake under an open, late afternoon blue sky. The man points to a small, stone cottage at the edge of the painting, where a rainbow beams down upon it. The young lovers, too, are headed home.

Then-Sen. Roy Blunt, R-Missouri, said during the ceremony, “(The painting) is sort of this ‘classic America as a paradise’ painting that a lot of painters were doing then. But for him, a Black artist, painting this painting that’s so much like an American utopia on the verge of a war that we would fight over slavery, makes all of that, I think, even more interesting. While he faced lots of challenges, (he) was optimistic, even in 1859, about America.”

The president and first lady were not expected to speak after Blunt’s presentation, but Jill Biden gestured toward the painting and called out through her mask, “I like the rainbow!”

“The rainbow is always a good sign,” Blunt replied before the applauding crowd.

The Cincinnati Art Museum is one of the world’s leading research institutions on Duncanson’s work. Julie Aronson, curator of American paintings, sculpture and drawings for the museum, said, “As a painter in the fashion of the Hudson River School, Duncanson often used nature allegorically. The rainbow that Dr. Biden admired as a symbol of the promise for the future surely took on special meaning for the artist, especially as an African American in the era around the Civil War. It is a tribute to Duncanson’s artistry that his paintings still speak to us so powerfully today.”

In the Los Angeles Times, art critic Christopher Knight said at the time of inauguration:

“Duncanson’s rainbow precedes the brutal devastation of the Civil War that erupted the next year. ‘Landscape With Rainbow’ is a cautionary image, painted as the seams of American union were being pulled apart. But it carries with it an unmistakable ray of hope: Rainbows typically appear after a storm has passed, not before.

“The painting is also likely indebted to the widely known Black spiritual, ‘Mary Don’t You Weep,’ which dates from before the Civil War. In the biblical story of Mary of Bethany, which relates her plea to Jesus to raise her brother Lazarus from the dead, the song includes a famous chorus invoking God’s covenant to Noah after the Great Flood.

“‘God gave Noah the rainbow sign; no more water, the fire next time.’”

As the war raged on, Duncanson became the most celebrated Black painter of his time by creating works of gentle beauty that quietly demanded justice and change.

Ties to Detroit

Duncanson, who had family in Michigan, was active in Detroit as early as 1846, and opened a studio in the city in 1849. He continued to travel between Detroit and Cincinnati for much of his life, and suffered a seizure while installing an exhibition in Detroit in fall 1872. Historians have suggested the cause may have been severe lead poisoning from years of working with lead-based paints. After his collapse, he exhibited symptoms of schizophrenia and dementia, strengthening the lead poisoning theory.

The artist was remanded to Michigan State Retreat, the state’s first private mental institution; Dearborn High School now occupies the property. His final months likely found him surrounded by alcoholics, Civil War veterans suffering from post traumatic stress disorder, and other patients, before his death in December 1872, at age 51. He is buried in Monroe’s Woodland Cemetery, where his resting place was the subject of headlines in 2019, when funds were raised to finally mark his grave with a formal headstone.

More: Pioneering black artist Robert S. Duncanson will finally get tombstone

More: After 147 years, DIA to unveil tombstone for pioneering artist Robert S. Duncanson

DIA director Salvador Salort-Pons said, “Michiganders have a deep connection to this selection of Robert Duncanson’s painting by Dr. Biden. Until late 2019 when the Detroit Fine Arts Breakfast Club raised funds to purchase and install a gravestone, DuncansoDun was buried in an unmarked grave in Monroe, Mich., where his family had roots as carpenters. The DIA proudly owns six works by the artist, mostly acquired through donations to the DIA in the 20th century. These works are among the highlights of our collection of African American art overseen by the Center for African American Art, the first curatorial department dedicated to this area of study at an encyclopedic art museum.”

Contact Free Press arts and culture reporter Duante Beddingfield at dbeddingfield@freepress.com.