Adorned in a daura-suruwal and dhaka topi set, Nelson Ferreira welcomes visitors to his PlatiGleam exhibition at Nepal Art Council, on display until April 2.

Upon entering, visitors are greeted by seemingly blank white canvases hanging on the walls. Even if you get really close and stare for hours, you won’t see much. But don’t give up just yet!

To view the paintings, stand back, use your phone’s flashlight, and shine it towards the canvases. The farther you stand, the clearer the images become. Seeing the paintings feels like an out-of-this-world experience.

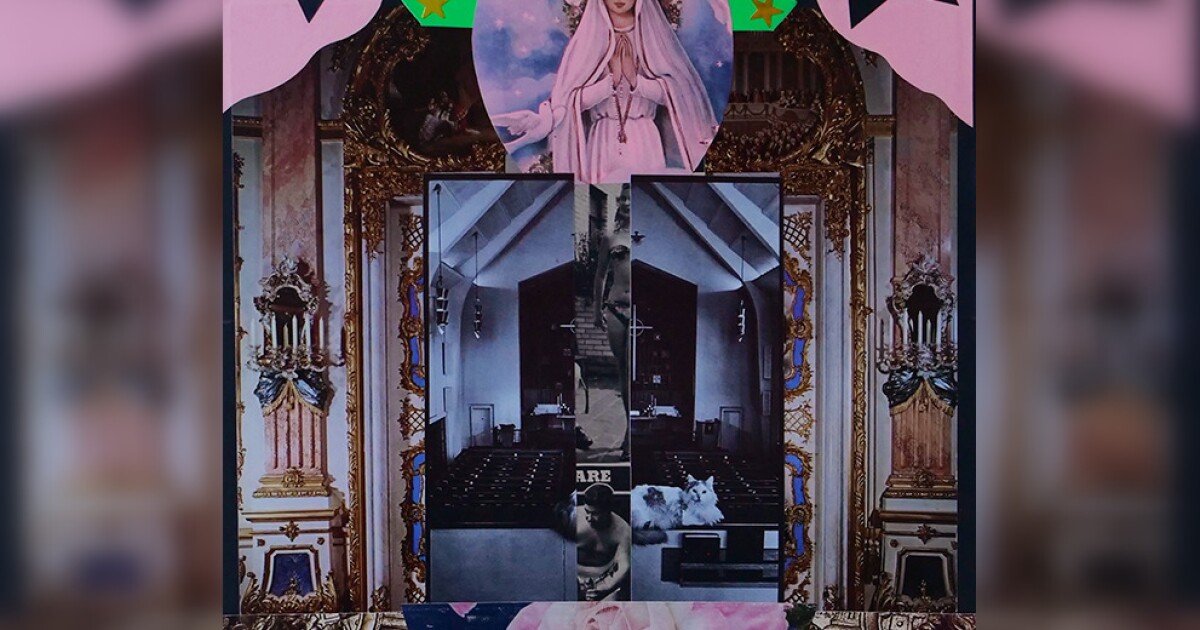

Portuguese artist Ferreira is the creative force behind this unique light-based art. His PlatiGleam series, comprised of five paintings showing the Monastery of the Dominicans of Batalha, doesn’t use any paint or pigments.

Ferreira is renowned for his expertise in ancient techniques and diverse cultural interests, focusing on traditional European methods like Primitive Flemish oil painting and 19th-century academic style. He teaches Flemish oil painting techniques at the Museu de Arte Antiga (Portugal’s National Gallery), University of the Arts London (UAL) and Galeria Monumental, and classical drawing techniques at the Victoria and Albert Museum. He is also a guest artist for the National Portrait Gallery.

His expertise extends to Russian and Greek iconography, Turkish marbling, and Indian miniature painting, which he shares globally, including in London, Portugal, and through workshops during his tours in Bangladesh and Nepal.

In an interview with the Post’s Aarati Ray, Ferreira talked about his ongoing exhibition of PlatiGleam artworks, the origin of the technique, his experience touring Asia, and the challenges faced by current artists.

What is the PlatiGleam technique?

PlatiGleam is an innovative reflective technique that doesn’t rely on pigments. It creates different reflective effects based on how light hits it, encouraging viewers to engage actively and pay close attention. Sometimes, viewers use a flashlight or mobile phone to enhance their experience.

The artworks were made at night in the historic mediaeval monastery of Batalha, a UNESCO World Heritage site in Portugal, and were also displayed there.

How did the idea of PlatiGleam come about?

Every morning, I would write down all my thoughts in a diary, but then I would forget about them later. After three months, upon revisiting these pages, I was surprised to find that by piecing together different fragments and details, they revealed the secret to the PlatiGleam technique.

How was your first painting using the PlatiGleam method?

My first painting using the PlatiGleam method was a disaster. One thing I didn’t realise at the time was that the liquids spread uncontrollably, similar to Japanese and Chinese paintings on rice paper.

Humidity caused the painting to turn black, which completely flabbergasted me. It was only very later I found out that it would revert to its normal state when dry. Even if you put water on it, it dries and can be displayed without exterior protection.

Did you paint the cathedral because it holds significance related to Portugal’s independence?

No, my motivation for painting the Monastery of the Dominicans of Batalha’s cathedral wasn’t tied to Portuguese independence. I don’t see countries as real, tangible entities. I admire this historian, Yuval Noah Harari, who says if you want to know if something is real, ask if it can suffer. Portugal can’t suffer, but Portuguese people can. Countries don’t have feelings, they’re not real in that sense.

I painted the monastery for its aesthetic appeal, especially its captivating energy at night.

Do artists nowadays often mix political ideas with their art?

Yes, it’s a common trend in contemporary art. Many artists today like to incorporate political messages into their work. Personally, I don’t like it when art tries to dictate what people should think. It reminds me of dictatorships and propaganda art. I prefer art to be free from trying to persuade or influence. I hate when art becomes a pamphlet.

What do you think about art combined with activism?

I believe activism is important, but I don’t think art always needs to be mixed with it. It’s a choice, not an obligation. Nowadays, there’s a trend where paintings are judged based on how political they are, and nonpolitical art is being dismissed by museums. I’m pushing against this trend by making deliberately non-political art.

The great power of art is to create a divergence of thoughts. Ask twenty people what they think about one piece of art, and you will get hundreds of different interpretations. Art was always important as a seed for democratic thoughts, for a plurality of thoughts. If we tell what to think, we are murdering one of the biggest qualities of art, which is the plurality of thoughts.

I feel it’s a civilisational failure to attack the non-political art. Just as scientists aren’t pressured to make certain statements in their experiments, artists should be free to create without being pressured to make political statements.

Has your admiration for mediaeval-style buildings influenced your art?

Yes, it has. I’m like a chameleon in my approach to art. While many artists stick to one specific style, I deliberately change my style every year or two. This surprises people because my paintings always look different. For example, my PlatiGleam series is nothing like my Blue series, and neither of them resembles my black paintings much.

I started as a contemporary artist. But as I learned more about art, I realised that contemporary art wasn’t as relevant as I thought. I saw how much better the old masters were at painting than I was, so I decided to learn proper techniques from them. Learning classical techniques involves many corrections and humbles your ego because you realise how many mistakes you’ve been making.

Unfortunately, there aren’t many institutions in the West where classical techniques are taught extensively, except for expensive private schools. Nevertheless, I’m committed to learning, teaching, and incorporating classical painting techniques into my work, including the PlatiGleam paintings.

You mentioned that each of your paintings is unique. If you were to select a favourite among your series, which would it be?

My favourite series is the one I haven’t made yet. The best painting is always the one in your imagination, your next dream. Right now, I’m focused on exploring more of PlatiGleam series. I envision creating huge pieces once I have proper sponsors. These paintings will be the best I’ve ever done.

I dream of painting entire rooms using the PlatiGleam technique. Imagine walking into a room and turning on the lights on your phone, only to see the entire room flashing with paintings on the floors, walls and ceilings.

In the future, I also aim to collaborate with architects to create large murals that reveal hidden images under specific conditions like car lights at night or humidity levels. Currently, I focus on small paintings for exhibitions until I secure sponsors for larger projects. Once these murals are realised, my creative potential will be limitless.

What challenges do artists face today?

During the Renaissance, art flourished thanks to visionary and wealthy patrons who realised the importance of art. Today, because of capitalism and consumerism, artists face the challenge of creating art first and hoping to sell it. We need more support for artists to produce meaningful work that shapes our civilisation. If you have the means, please financially support artists.

Masterpieces take time, and artists struggle without proper backing. I believe it is the responsibility of people in power to support intellect, genius and vision. Censorship is another big challenge for today’s artists.

Some individuals in the art world find PlatiGleam revolutionary. Would you consider yourself a pioneer of the technique?

It could be revolutionary because the PlatiGleam technique’s durability, demonstrated through accelerated ageing tests, surpasses that of acrylic and other paintings. It can withstand outdoor conditions for centuries.

I have done extensive research and I am still researching but I have not found anything even remotely close to the PlatiGleam technique. So, I believe this might be the first time anyone has worked on PlatiGleam. It’s plausible that someone else may have experimented with it but perhaps they didn’t put it online.

Where is your next destination for PlatiGleam?

After Nepal, I will be off to the Czech Republic and then Saudi Arabia. After that, I’m gearing up for possibly the biggest exhibition of my career in the UK. It will be my debut in the country, and I anticipate the attendance of all my former students—they better show up! (Laughs)

You have toured in different parts of the world. Did you find any cultural differences in terms of how people perceive your art?

In Europe, particularly, I observed a phenomenon I call “zombification”. Many museum visitors seemed more focused on taking photos and selfies due to the influence of social media, rather than truly engaging with the artworks, leading to a sense of detachment. In the West, I’d estimate that less than five percent of the public genuinely engages with the art.

Conversely, my experience in the East, particularly in Indonesia, was quite different. There, traditional customs of tactile interaction with paintings posed an unexpected challenge, as people often touched the artworks. While this wouldn’t have been an issue with PlatiGleam pieces, it caught me off guard since I was exhibiting charcoal paintings.

In Bangladesh, I saw contradictory reactions. Some people loved my paintings, while others seemed genuinely displeased, which I found puzzling.

In Nepal, I was pleasantly surprised by the keen interest and proactive support from the media fraternity in promoting art exhibitions and the arts in general. I am noticing huge differences in different parts of the world. I am very curious about the reaction in Saudi Arabia.