The 1980s in New York marked a germinative period for the city’s graffiti scene, transforming it into a veritable kingdom rife with excitement and rebellious creativity. The rhythmic sound of shaking spray cans echoed through the city’s night, becoming the unofficial anthem of the streets. Graffiti writers, each armed and ready, were all striving to make their name known.

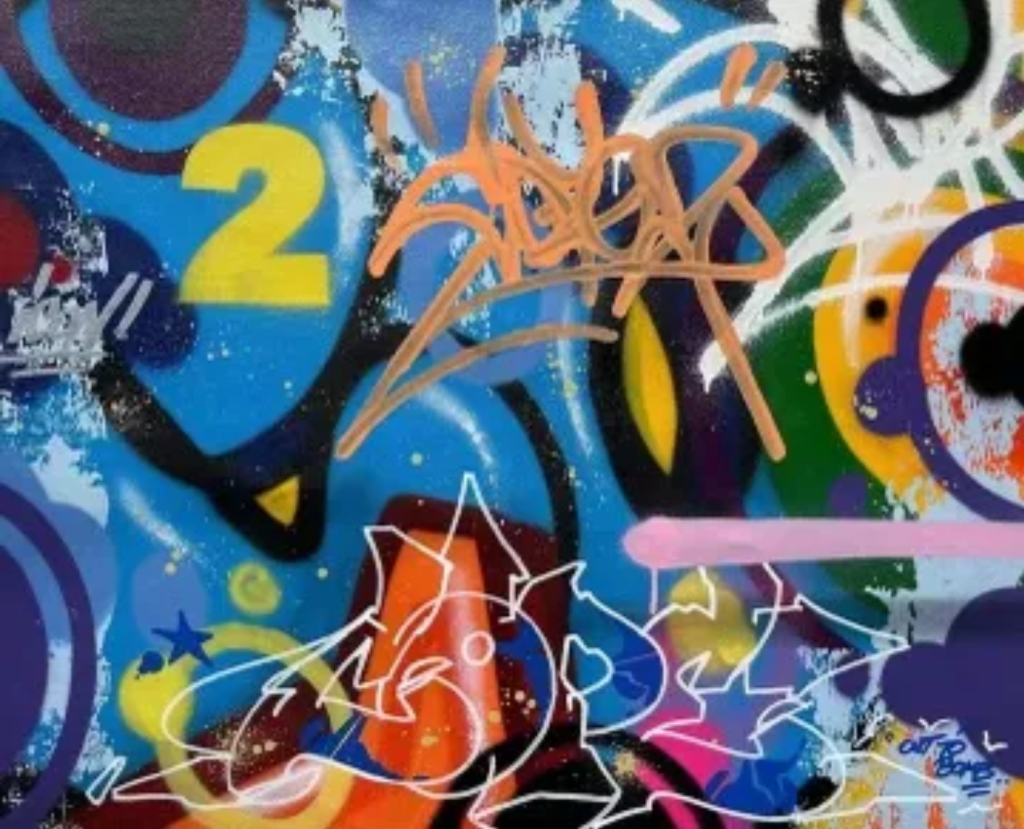

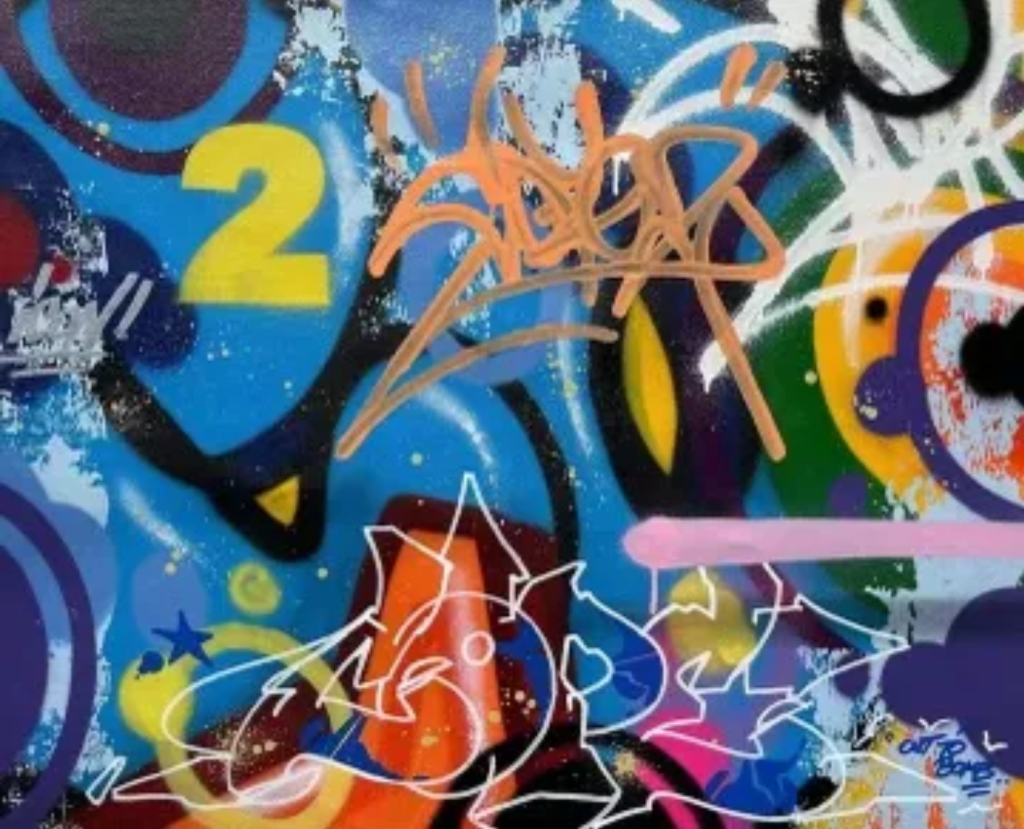

Image courtesy of Art Plugged

We became King of the 4 Line

COPE2

Writing, tagging, and bombing, they left enigmatic signatures sprawled across the walls as cryptic signs and symbols of individuality. Each mark was a bold declaration of existence, a defiant statement. They transformed New York City‘s terrain and its silver chariots into a battleground of expression, changing the city’s conventional aesthetics.

When it comes to bombing, one name that consistently stands out is Bronx-based graffiti legend COPE2. A complex figure in the world of graffiti, he is celebrated for his influential aesthetic and his no-holds-barred approach. For COPE2, ‘anytime, any place, any surface’ epitomises his method—his own words, ‘Kings Destroy.’

A master of throw-up and wild-style pieces, COPE2’s journey in the graffiti world began in the 1970s. His inspiration was sparked while travelling on the train with his family, mesmerised by New York’s aesthetic landscape. Discovering that his cousin, Chico, was a graffiti artist opened a new world for him. As he started meeting other graffiti artists in his neighbourhood, his passion for the art form ignited, setting him on the path to legendary status.

At night, COPE2 would bomb his tag in spray paint across the slumbering iron horses of the subway, transforming them from mere vessels of transport into moving masterpieces of graffiti, a gallery which in the morning travelled through New York’s veins, viewed by thousands. In 1982, he formed ‘Kids Destroyer,’ which later evolved into ‘King’s Destroyer’ as they transitioned from teenagers to adults, becoming a prolific graffiti crew known for, as their name implies, destroying surfaces with tags, bombs, and wild styles.

After conquering the streets, COPE2, like many graffiti artists, ventured onto canvas and gallery walls, travelling the world and collaborating with brands like Adidas. Yet, his rise from the canvas of the streets to international acclaim wasn’t without hurdles. Over the years, COPE2 has faced controversy and legal challenges regarding his public expressions, which are often viewed as vandalism by authorities. This duality of acclaim and legal challenge underscores graffiti’s complex position in society.

COPE2’s style, characterised by abstract gestures, bubble-shaped lettering, and wild styles, translates on canvas into a spontaneous flurry of bright, bold colors, shapes, and trademark tags. Layered with paint, it creates a dynamic tension, evoking the palimpsest nature of a freshly bombed train or wall.

COPE2’s legacy is a chaotic symphony of raw emotion and unfiltered expression, constantly evolving and elusive. In the city’s depths, away from sanitised galleries, it’s a high-stakes game, a thrilling blend of artistry, spray paint, and adrenaline. Subway writing, tagging, and bombing remain the purest forms of the graffiti artist’s soul—vibrant, defiant, and alive.

Under the shelter of the stars, these street monarchs undertake their silent crusade. In the city’s trenches, these kings stand immortalised, turning urban surfaces into museums of triumph, for kings become kings by conquering the people’s hearts, embodying the essence of a graffiti artist.

Like the Lannisters of Westeros, COPE2 plays for keeps. Forty-plus years into his career, he is still adhering to the crusade of graffiti bombing. I spoke with the Bronx graffiti legend during his solo exhibition at London’s creative hub, D’Stassi Art, delving into his artistic methods, sources of inspiration, and his journey in the graffiti world.

Hi COPE2, for those who might not be familiar with your work, please tell us a bit about yourself

COPE2: Hey, my name is Cope2. I’m a Bronx graffiti legend. I’ve been doing graffiti art for about 40-plus years from the Bronx, New York.

Starting from the streets of the South Bronx, can you tell us about your early experiences with graffiti? What initially attracted you to this form of art, and how did you begin your journey as a graffiti artist?

COPE2: Man, it started being a kid. You know, just taking the subway cars with my mom and friends. We would take a lot of train rides, and we would always see the graffiti on the outside. I’m talking late ‘70s. You know, looking at the graffiti, just like boom. I was like, wow, you will see – I would see these big pieces by Blade andComet some Tracy 168; these things inspired me. Even Lee had some cars. So it was like, wow, what is this? It was just the impact of it that really started me until I found out my cousin was tagging—he was tagged as Chico in the neighbourhood, and see, he did graffiti. So I was like, “Oh, you did graffiti, too?” And from there, I started meeting other graffiti artists in the neighbourhood, and it just took off. I started painting subway cars.

In 1982, you formed ‘Kids Destroyer’ later known as ‘King’s Destroyer’ a prominent graffiti crew in the 1980s and 90s. Could you share insights into that era, some standout moments, and how they influenced your artistic development?

COPE2: Growing up and watching graffiti, you always notice crews, and I was like, “What is this?” You’ve seen an old TB, CIA, TVS, RTW. It was like, what is that? So, it was a crew of writers, like everyone had their own little crew.

It was almost like a gang, but it was a crew of graffiti writers that stuck together. So, it was like, I want to make one. Since we were kids and we were already destroying the trains.

So, I made Kids Destroyer and then as we became King of the 4 Line in 1983, we changed it into Kings Destroyer because we took King of the Line. As we were getting older, we were almost teenagers. We weren’t little kids anymore. So, we considered ourselves kings. The crew was and still is worldwide. I got writers from all over the world down in there. You know, representing KD, and it has been repping for over 40 years since we started Kings Destroyer.

Your practice blends street culture with traditional techniques in an abstract expressionist style, merging a flurry of words and tags. Could we discuss how you developed this style and your inspirations?C

COPE2: I developed my style by watching the guys before me and I received some really wild style pieces by Kase2, Mix 77, which was one of my definitely top – one of my top idols, T Kid. You know, these guys were like – would have burners. You could never read them until someone would tell you what it said, or they would tag on the side Kase2, TFP. You know, or Mix 77 Latin artist, you had these writers before me who did really wild style letters.

So I wanted to do that style, which was called traditional style, traditional New York style, and that’s how I started to develop my own style. It’s not my own, but that’s how I started to develop style from the writers before me and the graffiti writers before me. So I took the traditional style from the subway era and just kept on going with it and that’s how I developed my style.

Delving deeper into that question, I’m curious to know about your mindset and feelings just before you start painting a wall. What thoughts and emotions are you experiencing at that point, and how do they shape your approach and the outcome of the work?

COPE2: It all depends. I mean, if I’m going bombing, I just do it. I just walk around the streets and do my throw-ups, which are called classic throw-ups. It’s something quick. A lot of writers would do it—it’s like a two-colour quick throw-up to get your name in bubble style, to get your name out fast, so people know who you are. “Like, oh, there goes Cope, another one, another one.”

I learned that by watching the bombers before me, you know, like Iz the Wiz was one of my idols when it came to bombing, Comet, Blade, Seen.

These dudes, you know, PJ. These guys used to destroy the throw-ups, like all over BAN2. I always liked the whole throw-up date and the tags, and I started to do that real quick. But if you’re doing a burning, usually I would just get a bunch of colours together, and I am more freestyle. Some graffiti writers do their pieces on a black book or a sketch first. I don’t do that. I just get the colours together and go to the wall. I look at the wall, and I write off the head, like freestyle. To me, it’s natural. I burn the wall, and I pick the colours when I get to the wall.

I know writers who are just perfect. They have to use the right colours. They have to do the sketch. They will do the sketch they have on the paper on the wall. I never go to the wall with sketches. I’ve done it a few times because when I sit down and do sketches, man, a piece of work—tremendous!

I’m just natural. I do what automatically comes out of my head and just rock, and it depends if I’m doing a train. You know, you’re always nervous and a little stressed. You don’t want to get caught because it’s illegal. So you got to go in and do your thing and bounce. But, you know, once you get your energy and your ambition is pumping, man, you always execute your work.

Many Graffiti artists like yourself, have moved into gallery spaces. How has this transition affected your work, and what do you see as the future of street art in the gallery setting?

COPE2: Our transition to graffiti was kind of hard. I watched people doing it. They were doing it before me, like Seen and Dondi, Crash and Daze, and Futura. These are guys who were doing galleries quickly before me. They started from the subway area. In the early ‘80s, they were in there doing canvasses. So, I watched that for many, many years, and I went to a few art shows down in New York. You’re talking like the mid-to late 1980s, and you would see the prices on those paintings.

Like wow, 5000, 10,000, 6000 and I’m like Jesus Christ! So, I was like, you know, I need to do this and have a friend, Jon One. He’s like a legend in Paris. This guy does some really phenomenal paintings. He used to do subway cars in the early ‘80s. He inspired me and pushed me to do paintings.

I would run into him in Paris. Before I was doing canvas, I was doing graffiti events, which, in the early 2000s, people were flying me over to paint live at events in Italy, Paris, and Germany. That’s how it started, do an in-store, in a graff shop, and then I was like, you know, I need to do canvases, and people were telling me that you should do canvases.

So, I started doing canvases. At the time, “I was like, what should I do, and people were like, just do what you normally do in the street but do it on canvas, and that’s it”. That’s what people like Crash, Daze, Seen, and Futura did. When they did subway cars, they just did it right on the canvas. Some of them twisted a little, did a little – you know, you got to try different things because at the end of the day, you are an artist.

You’re not just a graffiti artist. You’re an artist, so you always try to throw them something different than what you would do on a wall. So, it came out pretty normal and naturally. For the past 10 or 15 years, the galleries have been really into street and graffiti art. They call it urban art because it’s like graffiti and street art, two different styles of art. But both of them are almost illegal. You have street artists who run around doing stencils and wheat-pasting stuff. With a message, that’s more kind of street art. Then you have the graffiti artists who go around and really smash it up with spray cans, do big tags, big bubble letters, big burners, and big block letters.

It’s two different worlds, but at the end of the day, it’s called urban art because it’s from the urban areas when you have these big art festivals, they call it urban art festivals or when a gallery in France or Germany or even London does a group show now. They call it an urban art exhibition because you got a mix of street artists and graffiti artists.

So it has been doing good from what I see and from what I know in the whole, it has its own world. It’s really amazing because graffiti has the – own world. You’ve got contemporary art. You’ve got pop art. You’ve got fine art, abstract. you know, you got all these different kinds of steps of art and we are graffiti artists. So, we have our own style of art, which is great.

You’ve collaborated with brands like Adidas and appeared in various media. How do you balance commercial success with staying true to the roots of Graffiti?

COPE2: I mean, you stay true when you’re younger, but the whole thing about staying true is just staying true to yourself and what you do in general as an artist. It doesn’t matter because I get older. You know, you’re hitting your late 40s. You’re hitting your 50s. You can’t really be painting illegally.

You know what I mean? You have kids, you have grandkids. It’s very tough to try to stay true. They call it not selling out, hardcore, you know. It’s really tough because when you get older, you have to pay the bills. So, if a big company like Adidas or Converse comes to you and wants to collaborate with you because they like your art and is throwing you twenty or thirty grand, you’re not going to turn it down. You just ask them what they want. “They’re like, we want what you do on the street but on our product, and like, wow, that’s kind of amazing.”

You know, when I did the project with Adidas, it was phenomenal. It was a big payday, and we did a big collection of different sneakers, jackets, hats, shirts, and pants. It was wild, you know. They flew me to London, Paris, Italy, and Amsterdam. It was an Adidas, Footlocker, and COPE2 collaboration. So they had me go to Footlocker, sit down, and sign products and their stuff, black box or whatever. It was an amazing project.

Having faced legal issues related to your art, how do you view the relationship between Graffiti and the law? What changes, if any, do you think are needed in how street art is legally perceived and treated?

COPE2: I mean, if you’re going to be doing illegal graffiti, you have to be prepared to pay the consequences, and the same goes for street artists.

You know, you get caught, you get caught. It is what it is. They have a task force, or sometimes they just have regular police walking around. If they catch you tagging, they’re going to lock you up. It is what it is, but it’s like me. I like to do illegal too because it keeps the fun and the authenticity of what I used to do.

I’m the type of guy who doesn’t just do galleries. I will go do a train if I can. I will go do something illegal. To me, it’s traditional. It’s original. You just gotta do it. The galleries are dope; it’s how I pay my bills and feed my family, but at the end of the day, I like to always do illegal graffiti.

To me it keeps me authentic as well. You know, so if anybody says, “Oh, Cope2, a sellout. He does galleries.” All right. Yeah, I do galleries. Yeah, cool. I did an illegal wall a few weeks ago. I did an illegal train when I was in Germany. I’m still keeping it authentic and real within myself as an artist because I love to do it, not for anyone else.

How do you respond to critics who cite your history of problematic statements and behaviours? Do you believe an artist’s personal actions should influence the interpretation of their work?

COPE2: Well, you know, it’s tough because no matter what you do, people are always going to say something. They’re always going to complain. That’s why, at the end of the day, you have to do it for yourself, and it gets tough with me. The thing with me is I come pretty much from nothing, from the Bronx, growing up poor, family on welfare. So, when I started to actually become successful with my art and travel the world, I had never seen that coming.

I mean, I came from painting subway cars. You know, selling drugs in the hood and working normal 9:00 to 5:00 jobs, painting illegally in the street, doing burners deep in the street, and I never thought, doing it for so many years and being a legend from New York, from the Bronx and graffiti has spread all around the world, that they would fly me all over the world to represent myself and paint.

So it was kind of crazy to travel the world doing your thing, and I started to get a lot of hate and jealousy. It’s like a rapper, a singer, an actor. You know, not everyone makes it. You know, you try, you try. But you have to stick to it. If you really want it, you have to stay focused, and you can’t give up because there’s always plenty of room for everybody.

So you can’t just be mad; I never got mad at another artist because he was successful. You know, I was just like, “Damn, if he did it, I could do it.” You know, just push harder to a point where I was able to do it, and you’re always going to get critics. You’re always going to get someone not happy with your artwork. Saying it’s not all that. It’s this, it’s that. Because I’m not the best artist, there are people way better than me, you know. But my style is versatile; I got tags, I got bubbles. I do wild style. I do abstract. Some artists can just do one thing.

They could just do one stick letter. They could do one stencil, and they still do great, you know, because they focused, and they continue, and they continue to a point where they don’t stop. You can’t give up. Some people do art, and they feel like they’re not getting anywhere and the artwork isn’t good enough, so they give up. But at the end of the day, if you do it just for you, everything falls into place.

What advice would you give to young artists facing challenges and controversies similar to the ones you faced in your career?

COPE2: That’s what is about your legacy. You get a lot of rumours out there, a lot of lies, that people do. They do that with everybody when you’re successful. If you’re not successful, nobody cares about you. The minute you’re successful, you get friends and especially with the internet, you can go on there and write anything about anybody and before you know it, it travels so fast that you could do a meme on somebody.

You could do Photoshop and something is crazy. The stuff I’ve seen is like, wow, you know. But at the end of the day, if you keep it within yourself authentic and truly yourself, when you’re dead and gone, your legacy, people will look back and say, yo man, that dude was one of the realists, the most illist and realist graffiti artist ever because I learned in life that everything falls into place naturally.

Looking back, what do you hope your legacy will be? How do you want to be remembered in the Graffiti community and the broader art world?

COPE2: You don’t have to always explain yourself about this and that. You know, lies and things that are made about you that are not true, in time, always come out. Truth always comes out naturally. “Oh, they said this about me; they said that about me” —I know it’s not true. So you let it go, and eventually, by nature, everything comes out.

By nature, it’s going to come out, and when the people see you at the end of the day when the smoke clears, they’re going to say, “Wow, that dude was straight up true. He was a true dude. He was a solid dude,” and that’s what it’s about, man.

Your legacy, you have to keep; some people fuck-up their legacies. They’re doing great, then they will do some fucked-up shit. They will do some crazy shit, and they’re just like, oh man. Not me, man. I stay as real as possible because life is real, and it’s not a joke. You have to stay as real as possible and as genuine as possible, and in time, it will come out.

What future projects are you most excited about, and how do they reflect your growth as an artist and individual?

COPE2: Growth as an artist. I just continue to grow every day. Right now, my projects are more about galleries. I just did something with a big clothing line called Live Fast, Die Young.

It’s an urban clothing line from Dusseldorf, Germany and they flew me into Berlin to promote the collection. I get hit up with a lot of stuff. A few months ago, I collaborated with Patrick Ewing from the Knicks. He has his own sneakers, and I did a collaboration with the Ewing Sneakers. So it’s like people out of nowhere.

Like tomorrow, I can get hit up from who knows, Versace. You know, I wish. I would love to do a collaboration with Versace. That’s one of my dreams, but who knows. I don’t think they ever did anything with a graffiti artist, but you never know. It’s always like every day there’s always something new. But every day I’m always painting. I’m just moving forward and keep rocking. You know, so just keep – how do you call it? Focused, man. You got to keep focused and just keep going.

Lastly, what does graffiti mean to you?

COPE2: Graffiti means to me what it was like back then to become a king in the subway area and to get your name up. You know, to get your name famous. That’s what it was about; I’m a graffiti writer. I want to get my name up. I’m Cope2. I want to be famous. You know, so that’s what it was. It was about your own little world to represent yourself besides your normal name, which is just your family name. You had like this own little secret – a name or identity. It’s almost like a villain or a superhero. Hey, I’m Cope2, and I want to be famous around the whole world.

That’s what graffiti was about, to get your name up and become famous. To me, it’s always still the same, no different, you know.

I’m a graffiti writer, and I started to get my name up. I’m fortunate to have become one of the legends from New York. I guess putting in almost 50 years doing this. It’s crazy to think about it. When we did the subway cars in the early ‘80s and then to be travelling the world doing graffiti, its really phenomenal. I’m blessed, and I’m thankful for it, and I’m going to continue to do it. It’s my life. It’s my passion and my business. That’s what I do 24 hours a day.

©2024 COPE2