The image—created by legendary Japanese artist Katsushika Hokusai nearly 200 years ago—has been turned into an emoji, is appearing on a Japanese bank note this year, and has inspired countless artists across decades.

With the iconic artwork returning to the Art Institute’s galleries this fall (on view September 5–January 6), we’re taking a look—with help from Janice Katz, Roger L. Weston Associate Curator of Japanese Arts—at the facts behind the ever-fascinating work.

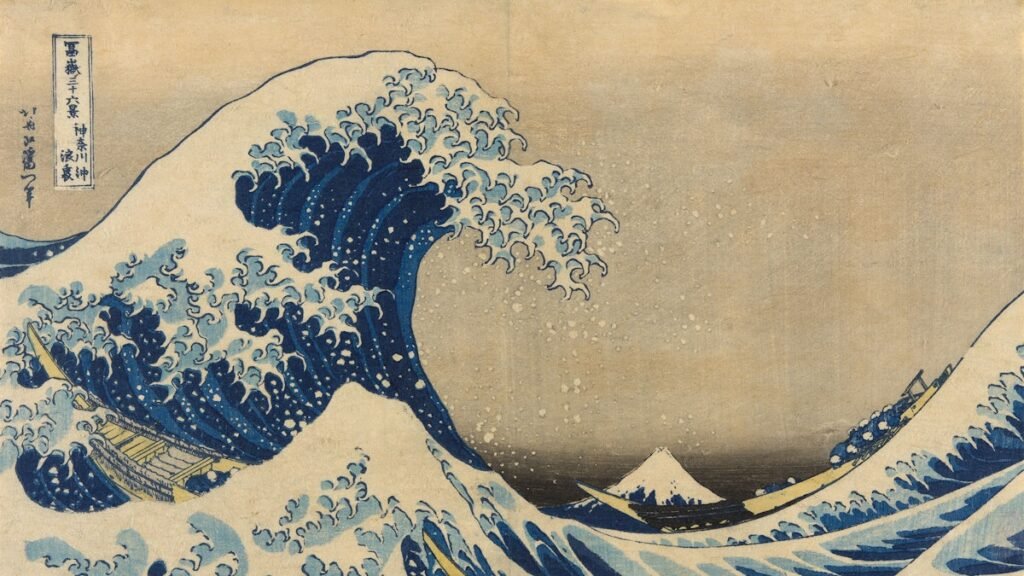

1. The Great Wave is a print.

Katz notes, “People don’t always realize that it’s not a painting but a print that was commercially produced for the mass market. Originally thousands of copies and different editions were produced over a period of many years, even after the artist’s lifetime. And while only about 100 original prints are thought to survive to this day, the Art Institute is fortunate to have three prints of The Great Wave, all original editions.

2. The Great Wave is not the print’s actual title.

It’s an English nickname. The title, which appears on the print in the upper left, is Kanagawa oki nami ura, which translates to Under the Wave off Kanagawa.

The title of the series and print appear in the rectangular cartouche, and the artist’s signature is to the left.

3. Because it’s a work on paper, The Great Wave is on view for only three months every five years.

Japanese woodblock prints are particularly affected by exposure to light that can fade their colors and damage the paper they’re printed on. “It’s always a balancing act between wanting to show works like The Great Wave so that our visitors have a chance to experience them and preserving these works for the future,” Katz says. “We work closely with our conservators to set the parameters for the display of works on paper.”

4. The Great Wave is one of a series of prints designed by Hokusai that feature views of Mount Fuji.

Though rather diminutive in The Great Wave, the famous peak and still-active volcano is central to the print and the entire series, Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji, which captures the mountain from various angles, in different seasons, and in all sorts of weather. Sometimes the peak is clearly the star, almost filling the entire composition, and other times, like in The Great Wave, one has to hunt for it far off in the distance. The series was so successful that an additional 10 prints were added just a few years after the original 36, and eventually a three-volume book was published, One Hundred Views of Mount Fuji.

5. The Great Wave may have appeared even more formidable to its original Japanese audience.

Because Japanese text is read from right to left, the earliest viewers of The Great Wave would have likely read the print that way too, first encountering the boaters and then meeting the great claw of water about to swallow them. So instead of riding along with the gargantuan wave as you might in a left-to-right reading, they would face right into the massive wall of ocean.

Reading The Great Wave in Reverse

6. Many of the prints in the series, in particular The Great Wave, are distinctive for their liberal use of blue.

Both traditional indigo and the newly affordable Berlin blue—popularly known as “Prussian blue”—imported from Europe were used to create the many subtle shades of sea and sky. This captivating color, which would have been novel to many of the print’s original Japanese viewers, might be part of its appeal.

A sample of Prussian blue, invented in Europe in 1706

7. Hokusai began the series when he was 70 years old.

In his late 60s, just before the publisher Nishimuraya Yohachi commissioned Hokusai to produce a new series—what would become Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji—Hokusai had suffered a series of tragedies. He had a stroke, his wife died, and all the while, he was dealing with a grandson who was running up gambling debts that threatened the whole family’s financial situation.

Portrait of Katsushika Hokusai, year unknown

“No money, no clothing, barely enough to eat,” he wrote. “If I can’t make some arrangement by the middle of next month, I won’t make it through the spring.” Obviously, an arrangement was made, and Hokusai, clearly boosted by the success of his Mount Fuji series, went on to say, “All I have done before the age of 70 is not worth bothering with,” implying that his best work was yet to come.

8. Hokusai was a member of a religion centered on Mount Fuji that flourished during the Edo period (1615–1868).

Mount Fuji had been viewed as a sacred site since ancient times, but the long-revered peak became more of a presence in many Japanese people’s lives when the capital of the country moved to Edo (present-day Tokyo). The unwalled city left residents with a clear, unobstructed view of the spiritual mountain. Devotees made pilgrimages up the mountain, and numerous smaller replicas, some as tall as 50 feet, were made for those who could not undertake the arduous journey up the actual peak.

Later in his life, Hokusai incorporated a stylized design of Mount Fuji into his signature, or artist’s seal, as seen at left.

9. Hokusai was likely inspired to take on the subject of Mount Fuji by earlier depictions of the mountain.

One such large-scale painting of Mount Fuji—one of the earliest known to exist—is part of a pair of screens titled Mount Fuji and the Miho Pine Forest, made by renowned Japanese painter Soga Shо̄haku around 1761–62. Shо̄haku was a mysterious figure, revered for his unusual subjects and eccentric painting style. In his screens, which just recently came into the museum’s collection and debuted in the galleries, Shо̄haku used almost entirely black ink to evocatively depict the landscape’s rocks, mountains, and trees—as well as the ephemeral, intangible wind, rain, and clouds.

Katz adds, “Mount Fuji is shown completely covered in snow in winter, and Shо̄haku painted it in the negative. The white of the mountain is the color of the bare paper, and the outlines of the peak are done with ink wash. This is one of the earliest and largest painted images of Mount Fuji in premodern times and a direct antecedent of Hokusai’s images of the mountain.”

10. The Great Wave has in turn inspired many other artists.

Truly there are too many to count, so here’s just a few:

French composer Claude Debussy owned a copy of the print, and his 1905 composition The Sea (La Mer) was inspired by it. His first edition of the score used a detail of the print (no Fuji or boats) in muted colors as its cover.

The cover of Debussy’s first edition of La Mer, 1905

Austrian poet Rainer Maria Rilke’s 1908 poem The Mountain is thought to have been inspired by the print.

Sculptor Camille Caludel replaced the boats in Hokusai’s image with three women holding hands in her onyx work The Wave or the Bathers.

It has been suggested that Vincent van Gogh was influenced by The Great Wave when creating his swirling and blue-heavy masterpiece The Starry Night.

I did not know that one could be so terrifying with blue and green…these waves are claws, the boat is caught in them, you can feel it.

—Vincent van Gogh

Letter to his brother Theo, September 8, 1888

Vincent van Gogh

The Museum of Modern Art, New York, Acquired through the Lillie P. Bliss Bequest (by exchange). Conservation was made possible by the Bank of America Art Conservation Project

Modern and contemporary artists who were influenced by the work include Roy Lichtenstein, Andy Warhol, Loïs Mailou Jones, and Yoshitomo Nara—and more!

11. And of course, as with any image that has been burned into the global cultural psyche, The Great Wave has inspired hundreds of tributes and parodies.

Picture Cookie Monster as the wave, the foam turning into bunnies, the water composed of dozens of pairs of Levi’s, or the wave carrying surfing cats, sleeping cats, frolicking cats, bored cats … so many cats. Or, just google it.

Now that you’re armed with all these fun factoids, be sure to catch the once-in-five-years appearance of The Great Wave in the Art Institute galleries. The print will be on view in the Andо̄ Gallery (107) September 5, 2024, through January 6, 2025.