Hear the word Surrealism and Salvador Dalí will most likely spring to mind—if not the artist himself, then certainly his signature icon of a melting watch. Known for his theatrical behavior and appearance (especially his cartoonishly waxed mustache) and for paintings (frenzied swirls of delirious, if not demented, subject matter) and found-object sculptures (e.g., Lobster Telephone, 1938, a handset sheathed in a crustacean carapace), Dalí became synonymous with Surrealism, much to the consternation of the movement’s founder, André Breton, who came to resent Dalí’s success.

Dalí’s legacy rested as much on the precedent he set for the artist as superstar brand (anticipating Warhol and Koons) as it did on his work. He also embodied the deleterious effects of such celebrity, becoming a caricature of himself whose antics and tendency to dump too much product into the market wound up diluting his art. More troubling was his flirtation with fascism during the 1930s, which cost him his place in the Surrealist circle.

-

Early Life

Image Credit: Collection of The Dalí Museum, St. Petersburg, Florida. Copyright © Salvador Dalí, Gala-Salvador Dalí Foundation/DACS, London 2023. Photo copyright © David Deranian, 2021. Dalí was born in 1904 in the Catalan town of Figueres, Spain. His father, a lawyer, was a strict disciplinarian with anticlerical leanings who supported autonomy for Catalonia; his mother, meanwhile, encouraged Dalí’s artistic ambitions.

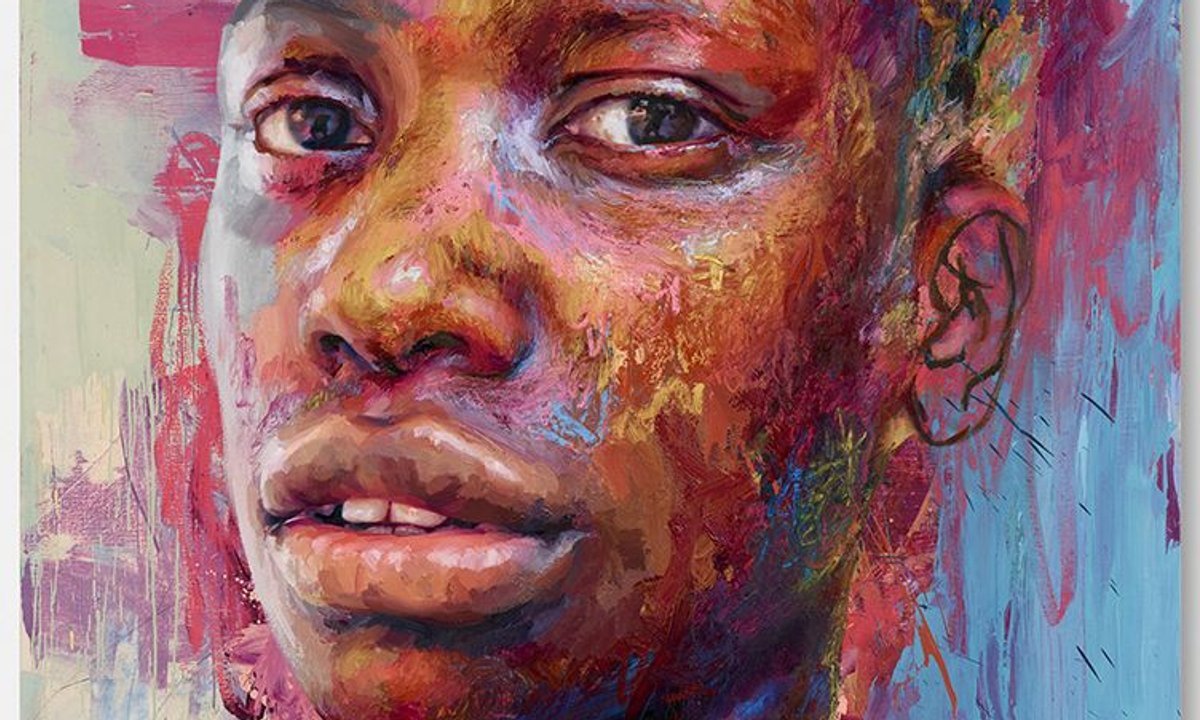

He was the second child called Salvador: Nine months before his birth, an older brother with the same name died at age three. When Dalí turned five, his parents told him that he was a reincarnation of his sibling, which haunted his life and art until his dying day. “I thought I was dead before I knew I was alive,” Dalí said of the specter hanging over him. In 1963 he painted Portrait of My Dead Brother a Pop Art-like exorcism in which he imagined his namesake as an adult, rendered in benday dots.

Dalí also knew that his surname wasn’t Spanish or Catalan, but native to North Africa, suggesting a connection to the Moors who conquered the Iberian Peninsula in the eighth century. This was enough for Dalí to claim Arab lineage, which he said accounted for his love of ornamentation and his skin turning unusually dark when tan.

-

Education and Early Career

In 1916 Dalí began his studies at the Municipal Drawing School in Figueres. He became acquainted with the avant-garde through the Catalan Impressionist Ramon Pichot, who regularly visited Paris. Pichot introduced the young Dalí to the work of Picasso and the Futurists, both of which would influence Dalí’s oeuvre even as it maintained a strong attachment to realism.

In 1921, Dalí’s mother died, dealing him a deep blow. The following year, at age 17, he entered Madrid’s San Fernando Royal Academy of Fine Arts, Spain’s preeminent art school.

Initially Dalí’s focused on landscapes and portraits, but soon enough his art became characterized by willful weirdness. In his Self-Portrait with the Neck of Raphael (circa 1921), he melded Fauvist colorism with Mannerist distortion, portraying himself in three-quarters profile with a towering, torquing neck straight out of a Parmigianino Madonna.

Dalí could paint with near-photorealistic precision, a skill that undoubtedly factored into his work’s public acceptance. But even his most prosaic efforts could seem oddly estranged from the everyday, as in Girl’s Back (1926), whose turned-away pose put her at an enigmatic remove from onlookers.

Sigmund Freud was perhaps the greatest early influence on Dalí, who initially immersed himself in Freud’s theories of the id while still in school. He applied Freud’s thinking to his own, using it to channel his fears, desires, and neuroses through his art. He tried to meet the famed psychoanalyst several times, traveling to call upon him at his Viennese residence to no avail. In 1938, Dalí finally managed to visit Freud, in London, where he lived after fleeing the Nazi anschluss of Austria.

-

Dalí and the Surrealist Circle

Image Credit: Collection of The Dalí Museum, St. Petersburg, Florida. Copyright © Salvador Dalí, Gala-Salvador Dalí Foundation/DACS, London 2023. Dalí also read Breton’s Surrealist Manifesto of 1924, which laid out the concept of automatism, calling for writing or making art without conscious thought or intention. In 1926 he moved to Paris, his reputation preceding his arrival thanks to fellow Catalan Joan Miró, whose own biomorphic compositions had inspired the younger artist. Miró, who’d joined the Surrealist movement at its inception, introduced Dalí to Breton and Picasso, as well as to his own gallery dealer.

Dalí’s first Surrealist painting, Apparatus and Hand (1927), depicts a bizarre figure comprising an elongated pyramid precariously perched atop another geometric solid with needle-thin legs; it stands on a barren plain beneath a turbulent vortex of clouds and sky lofting objects (a nude female torso, a flock of birds) into the air. Whatever its meaning, Dalí maintained that this vision sprang from the deepest recesses of his subconscious.

Dalí quickly assimilated others’ ideas, especially those of Yves Tanguy; according to Dalí biographer Ian Gibson, the artist allegedly told Tanguy’s niece, “I pinched everything from your uncle.” Dalí soon eclipsed Tanguy and other Surrealists in the public eye—which, as previously mentioned, got under Breton’s skin, though it would take a nearly a decade for things to finally come to a head between them.

-

Dalí and Luis Buñuel

Image Credit: FilmPublicityArchive/United Archives via Getty Images In April 1929, Dalí collaborated with the Spanish filmmaker Luis Buñuel—whom Dalí met while both were students in Madrid—on a short film financed by Buñuel’s mother: Un Chien Andalou. With its shocking sequence of a razor slashing a woman’s eyeball, the film became an immediate succès de scandale and was eventually recognized as a cinematic landmark thanks to its disjointed mis en scene, and free-associative montage of provocative imagery. A year later, the two went on to make L’Age d’Or, an in-your-face, satirical takedown of bourgeois sexual hypocrisy featuring interludes like one of a couple publicly fornicating in the mud, which fomented a right-wing riot during an early screening.

-

Dalí and Gala

Image Credit: Martinie/Roger Viollet via Getty Images In August 1929, Dalí received a visit from Paul Éluard, the cofounder of Surrealism, and his wife Gala, née Elena Ivanovna Diakonova. Ten years Dalí’s senior, Gala cast a spell on him, and they soon began an affair. (Her marriage to Éluard had previously involved a ménage à trois with the German artist Max Ernst). The two eventually married, and Gala became Dalí’s lifelong companion, model, and muse. However, Gala insisted on an open relationship—at least for her, since Dalí was reportedly more interested in masturbation than reciprocal sex.

-

The Surrealist Object

Image Credit: Collection Tate, London. Copyright © Salvador Dalí, Gala-Salvador Dalí Foundation/DACS, London 2023. Drama aside, Dalí did make important contributions to Surrealist ideology. When artists began flocking to the movement, Breton commissioned Dalí to come up with a motif that could span their diversity of styles and ideologies. In response, Dalí offered “Surrealist objects” as a unifying concept. Dalí’s proposal was essentially a psychosexual spin on the found-object aesthetic seen most conspicuously in Marcel Duchamp’s Readymades. But instead of puckishly violating the boundaries between art and life or between high and low culture, as Duchamp did, Surrealist objects would dredge up repressed thoughts and feelings. Dalí based the idea on Freud’s theory of fetishism, which explored the erotic fixation on shoes and other items associated with individual body parts.

Dalí’s own Surrealist objects, like Lobster Telephone, manifested his obsessions in physical form. Another piece, Surrealist Object Functioning Symbolically (1931/1973), incorporated a single red pump juxtaposed with items such as glass of milk, a knot of pubic hair glued to a sugar cube, a pornographic photo, and a wooden armature resembling a weighing scale; Dalí called it a “mechanism” for onanistic fantasies.

-

The Paranoiac-Critical Method

Image Credit: Collection Museum of Modern Art, New York. Copyright © Salvador Dalí, Gala-Salvador Dalí Foundation/DACS, London 2023. Concurrently, Dalí developed his “paranoiac-critical” method. Based on the notion that paranoiacs perceive things that aren’t there, Dalí’s “method” secreted phantom pictures within his compositions as a kind of stream of consciousness Rorschach test for viewers. Dalí called this strategy a “spontaneous method of irrational knowledge based on the critical and systematic objectivity of the associations and interpretations of delirious phenomena.”

Prime illustrations of Dalí’s paranoiac-critical approach include his masterpiece, The Persistence of Memory (1931), as well as Apparition of Face and Fruit Dish on a Beach (1938), both set along a shore fronting a bay. The former, a rumination on the relative nature of time, introduced what would become Dalí’s most enduring symbol: A pocket watch softened as if left in the sun for too long. By his own telling, the notion came to him in a reverie over a plate of overripe Camembert cheese. Apparition, meanwhile, centers on the doubled image of a footed bowl of pears, with its stem resolving into a ghostly face.

-

Fame and Fortune

Image Credit: Bettmann Archive Dalí avidly pursued money and notoriety at a time when the avant-garde considered such goals a betrayal of art. He was shameless self-promoter who admitted to having a “pure, vertical, mystical, gothic love of cash.” His first show in Paris at the Goemans Gallery in November 1929 was a commercial smash, though it left critics scratching their heads. His first visit to New York, in 1934, created a media firestorm, which he encouraged by spouting edgy statements like “The only difference between me and a madman is that I am not mad.” Before departing New York, he was feted with a costume ball thrown by Caresse Crosby, a Bostonian blueblood who also invented the brassiere. Dalí attended wearing a bra contained in a glass case strapped to his chest; Gala accompanied him dressed as a woman giving birth through her head.

Other stunts included a talk in London that Dalí delivered in a deep-sea diver’s suit, which almost asphyxiated him. For a lecture in Paris, he arrived in a Rolls-Royce filled with cauliflower. Such antics garnered him huge amounts of press, including an appearance on the cover of Time magazine in 1936.

-

Expulsion from Surrealism

Dalí’s politics leaned right, though it was never established that he was a full-blown fascist. He did support Franco during the Spanish Civil War and was also infatuated with Hitler, saying that he often dreamed of the fürher as a woman whose “flesh, which I had imagined whiter than white, ravished me.” The central figure of a wet nurse on a beach in Dalí’s The Weaning of Furniture-Nutrition (1934) originally sported a Nazi armband until Breton prevailed on Dalí to paint it out. In 1939 Dalí created The Enigma of Hitler, which featured a giant telephone receiver dripping viscous fluid onto a dish containing a tiny photo of the dictator. Dalí was also friends with Nazi sympathizer Wallis Simpson, the woman Edward VIII had abdicated his throne to marry.

Nevertheless, Dalí insisted, “I am Hitlerian neither in fact nor intention,” though that didn’t prevent Breton from seeking to banish Dalí from the Surrealist movement by putting him “on trial” in 1934 as a fascist. He barely escaped conviction, quipping in the end that “the difference between the Surrealists and me is that I am a Surrealist.”

Still, his support of Franco cost him friendships with Buñuel and others, and thanks to the outbreak of World War II in 1939, Breton finally engineered Dalí’s expulsion from the Surrealist group, accusing him of espousing race war. Breton also denounced the paranoiac-critical method, even though he’d originally hailed it as an “instrument of primary importance.”

-

Later Career

Image Credit: Collection Thyssen-Bornemisza National Museum, Madrid. Copyright © Salvador Dalí, Gala-Salvador Dalí Foundation/DACS, London 2023. Breton was as motivated by his jealousy of Dalí’s stardom as he was by the artist’s political incorrectness, an animus abundantly evident in the anagram he coined from Dalí’s name: Avida Dollars (“greedy for dollars”). Breton remained a nemesis for decades, going so far as to lobby for Dalí’s exclusion from a 1960 show organized by Marcel Duchamp in New York. (The attempt failed.) Dalí’s renown, however, continued to grow as he became more of a pop-cultural phenomenon than an artist.

The same year he was ousted from the Surrealists, Dalí designed The Dream of Venus for the New York World’s Fair, a sort of funhouse dedicated to the goddess of love that surpassed anything at Coney Island. He also became a presence in Hollywood, designing dream sequences for the noir romance Moon Tide (1942) and Alfred Hitchcock’s psychoanalytic thriller, Spellbound (1945), though both suffered cuts demanded by studio executives. In 1946 Dalí collaborated with Disney animator John Hench on a short called Destino, which never went beyond storyboarding and test footage. A version of sorts was completed in 2003, well after the artist’s death.

In 1948, Dalí appeared in a famed Life magazine spread, featuring a high-speed camera shot of the artist levitating in a studio complete with floating easel, step stool, and chair, along with a thrown bucketful of water and a trio of cats frozen in midair. The photo took 26 tries to complete.

Dalí licensed his name to a line of perfumes for Sears, which also sold framed reproductions of his work. Other commercial forays included appearances in TV ads for Lanvin chocolate, Alka-Seltzer, and Braniff Airlines, in which Dalí could be seen discussing the finer points of pitching with New York Yankee hall-of-famer Whitey Ford.

Dalí didn’t do anything that Warhol wouldn’t do later, though Andy never undermined his art the way Dalí did. In 1976 and 1977, Dalí signed and sold 17,500 blank sheets of paper with his signature, meant for printmaking ventures that never materialized; instead, they were used to create forgeries of his work.

-

Final Years

While never matching the heights of his early career, Dalí did have flashes of brilliance during his later years, such as the painting, The Hallucinogenic Toreador (1968–70). Depicting a succession of Venus de Milos receding across the floor of a Roman arena, it cleverly mirrored the era’s lysergic zeitgeist.

Starting in 1980, Dalí’s health began to fail with the onset of Parkinson’s disease and bouts of depression and drug addiction. When Gala died, in 1982, his condition worsened. He refused to eat, and he barely recovered from third-degree burns suffered during a fire in 1984. Dalí died of cardiac arrest five years later at age 84 in Figureres. He was buried not far from his childhood home, joining a brother whose fate hovered over a fantastical chapter in art history.